Library workers voice frustrations over compensation, morale and value of labor

January 23, 2026

“While Bowdoin enjoys national recognition as a top liberal arts college, the workers who sustain its day-to-day operations struggle to make their voices heard,” an anonymous library employee wrote in the Winter 2024 issue of The Bowdoin Orient Magazine.

It’s a sentiment echoed by many library staff at the College. Interviews with 11 current and former Bowdoin library staff and an Orient survey completed by two-thirds of non-management library staff revealed persistent frustrations around compensation, morale and the value of library work.

Segal Group and the Compensation Study

In 2023, Bowdoin’s Human Resources office (HR) commenced a months-long redesign of the College’s compensation scheme for non-faculty employees. To do so, the College procured the services of Segal Group, a New York City-based consulting company, to reevaluate the wages of 815 staff members. This project consisted of two main parts—a market-based study, followed by the creation of a new pay structure for College employees.

Shortly after staff learned of this study in May 2023, HR asked managers and supervisors across various departments to provide “stripped down” job descriptions for each of their employees. During this process, supervisors and managers were repeatedly encouraged to ‘separate the person from the job’ and reduce job descriptions to their most generic form to compare them to similar roles on the market.

Segal reviewed and further “stripped down” these descriptions, comparing them to jobs at other colleges and across the Portland metropolitan area.

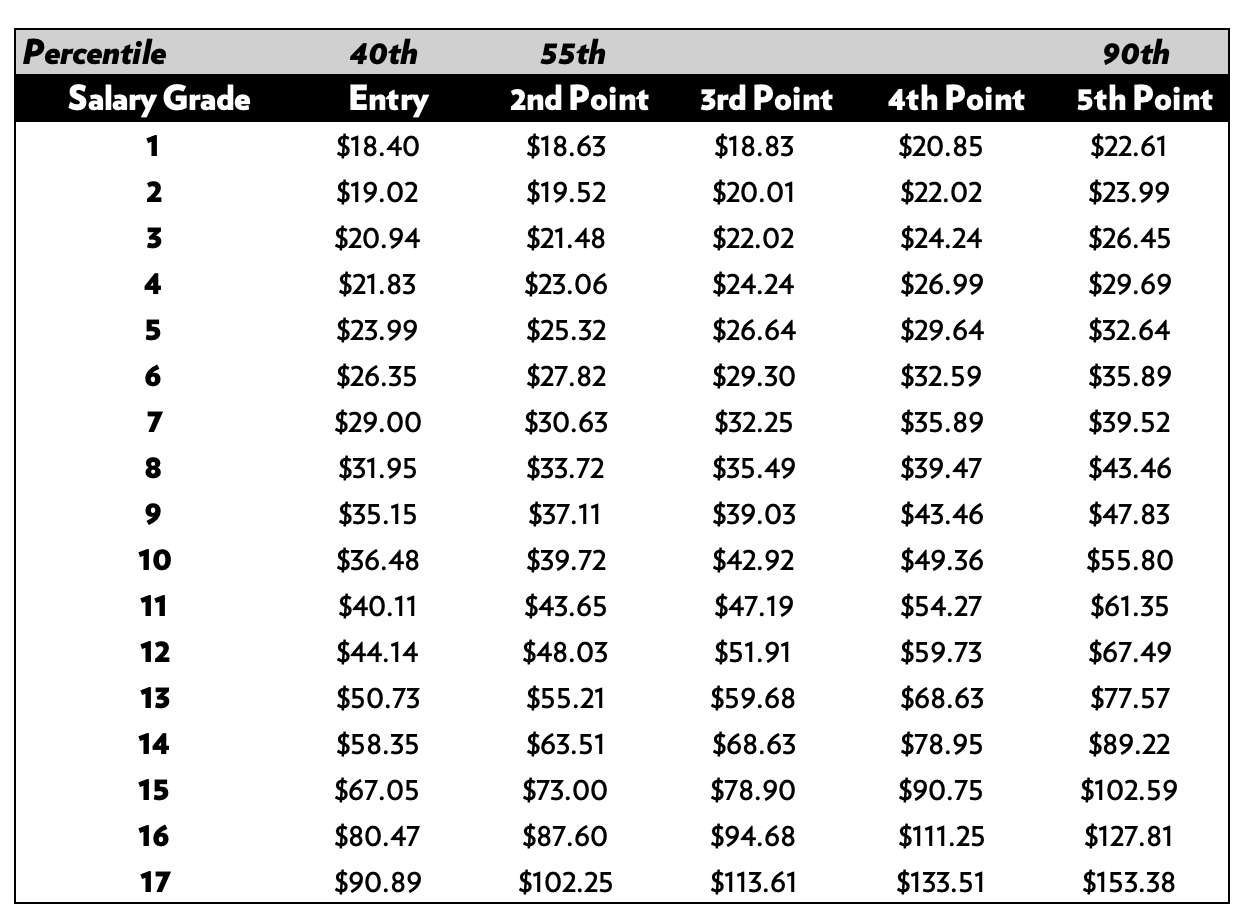

Employees were assigned a grade from one to 17 that corresponded to a salary range. A recently posted housekeeping position was listed with a Grade 1 salary of $18.40 per hour. In comparison, Bowdoin’s highest-paid executives receive six-figure salaries equivalent to or greater than those in Grade 17, amounting to over $120 per hour.

While Bowdoin has publicly stated that grades “[group] similar jobs based on the type and nature of work performed,” it has shared little about what specific types and natures of work fall into each category.

“[HR] has not explained how they decided what job levels to put positions in. They can’t tell us … because it’s proprietary information,” one library worker said. “They won’t even tell us if it’s an algorithm or AI.”

Courtesy of Human Resources

Courtesy of Human ResourcesPaid Less Than A Living Wage

Starting wages in the first five bands of Bowdoin’s reevaluated pay grades fall below $24.45 an hour, which the Massachusetts Institute of Technology considers the minimum living wage for a single, childless adult living in Cumberland County.

“There are a lot of people at Bowdoin who don’t make a living wage for themselves, let alone their families. I’m one of them,” an anonymous library worker said. “The cost of living is a real thing, and it’s affecting me now more than it has at any other point in my Bowdoin career.”

An anonymous survey conducted by The Bowdoin Orient of 20 non-management library staff found that two thirds of respondents struggled either some of the time or regularly to make ends meet on their Bowdoin paycheck, with 40 percent working another job, whether seasonal or year round, to supplement their income from library work.

“I think that no one at Bowdoin realizes that employees have to go to the food pantry. If your cost-of-living raise doesn’t even cover enough that, one, people can’t even live in Brunswick, [and] two, they have to supplement their income getting food from the food pantry, what are we even doing?” one employee said.

When reached for comment by email, Senior Vice President for Finance and Administration and Treasurer Matt Orlando praised Bowdoin’s pay structure.

“On average, we hire at levels higher than peers, and our employees move through pay grades faster than at other institutions,” Orlando wrote. “This is a generous pay strategy that reflects Bowdoin’s strong commitment to its employees.”

Hitting a Ceiling

Along with a numerical grade, every employee affected by the Segal study was assigned a percentile within their job grade. New employees receive starting pay fixed to the 40th percentile of market pay for their grade, with the ability to work towards the market’s 90th percentile, which HR calls the “market premium zone.” Any pay raise, including cost-of-living increases, awarded to an employee making above the “market premium zone”requires a second round of approval by College executives.

While Bowdoin has touted a 90th percentile wage as an indication of appreciation for exceptional employees, many, such as former evening circulation assistant Beanie Lowery, argued that it did the opposite.

“I was a level one, and I was in the 90th percentile of my pay already [after one year], so I was going to hit a pay ceiling very, very quickly,” Lowery said. “That was incredibly frustrating, especially given that I had just started. It felt like there was no room for upward growth [at Bowdoin].”

“If You Don’t Like It, You Can Leave”

After just one year at Bowdoin, Lowery resigned from his position at the College. He wasn’t alone. Alexander Elliott, a former employee in Collections Management, also resigned that summer. While Elliott attributed his departure to broader issues with workplace culture, the events of Segal’s compensation study only affirmed his decision.

“People were very demoralized,” Elliott said. “It confirmed that [leaving] was the right decision to make.”

Half of the library workers who responded to the Orient survey shared that they had considered leaving Bowdoin since the compensation study in 2024.

“My morale was lower than I ever thought it could be at work,” wrote one respondent.

In interviews with the Orient, numerous workers recounted Vice President of Human Resources Tama Spoerri telling library staff that employees could always leave Bowdoin if they were unhappy. But half of survey respondents who had considered leaving Bowdoin also said that doing so was not an option for them.

“We have had a strange relationship with morale.… Instead of people just leaving, there is this sense of, ‘where do we go?’, especially [for] folks who have families and care commitments here,” Emma Barton-Norris, a processing archivist at Hawthorne-Longfellow Library (H-L), said.

Some workers also expressed fears of retaliation.

“Look at how much money Bowdoin threw at breaking up the union for the student RAs. They brought in f**king union busters for Starbucks,” another library worker said. “What do you think is gonna happen with the library when [Bowdoin] clearly already indicates that they don’t care about [us]?”

How Much Is Library Work Worth?

Since its announcement, employees received few updates about the Segal study until they were told a year later by HR to expect letters listing their pay grade, percentile and new salary.

“We each got our letters sent to our home addresses, which I think kind of conflated the issue of the lack of information because everyone got their letters at a different time,” Barton-Norris said.

Multiple employees speculated that this was intentional.

“I don’t understand why they couldn’t have just put them in our staff mailboxes, except for discouraging talking about them,” Lowery said.

Whatever the intent of such a move, conversation spread quickly.

“[HR] didn’t realize that we would talk to each other about the letters,” an anonymous worker said.

“Library staff share everything. We knew what grades and levels people were put in,” another said.

Many were especially upset that a study publicly billed as a way to “maintain internal equity” seemed only to compound disparities at the library. These frustrations were detailed in a staff-written letter sent to library leadership the week employees received their new pay rates.

“Workers with nearly identical jobs have been placed three grades apart from each other,” the letter read. “Workers who have been at the College for less time have been placed in higher percentiles than those who have been here longer.”

For many employees, these disparities struck at something more profound. Some argued that these inequities were a natural outcome of applying a market-based model to library work, a profession that has long battled devaluation and disrespect.

“I think the wage study was a moment where the corporatization of Bowdoin that had been kind of under the surface for a really long time started to matriculate,” Barton-Norris said.

Orlando acknowledged library workers’ concerns but stood by the College’s market-based compensation structure.

“My understanding is that the source of the frustration is that Bowdoin uses competitive market data to benchmark pay, and there is concern that librarianship is an underpaid profession in the marketplace,” Orlando wrote. “The College’s compensation policy has been, and continues to be, market-based, with an important commitment to being among the leaders in the market.”

But for many library workers, this reasoning offers little comfort.

“You’re a liberal arts college that embraces the common good, and yet you’re basically endorsing an entirely capitalist, market-based system to pay your employees,” one employee said. “What does that say to Bowdoin students who are majoring in a [subject] that doesn’t typically make a lot of money? You’re almost devaluing your own degree.”

The Role of Student Supervision

Another widely expressed frustration surrounding the compensation study was its treatment of student supervision, a prominent responsibility for many staff at the third largest employer of students on campus. A webinar conducted by Bowdoin’s HR department emphasized that only workers who “manage [at least] one benefits-eligible person, not just a student or a casual” were considered managers. Many workers argued that discounting student supervision as a form of managerial responsibility only inflamed feelings that Bowdoin did not value the work of library staff.

“It takes twice as much effort and time to supervise students than it does a full time [employee], rightly so, because this is probably their first professional job, and creating a safe environment for their learning is why the College exists,” one library worker said.

“Historically, supervision of students has been undervalued,” they continued. “When this study from an outside company paid the lowest possible wage to two people at H-L who supervise 50 students on their own while the rest of the staff is off nights and weekends … that’s when I found out it’s cemented [at Bowdoin].”

Some workers also argued that this devaluation of specific responsibilities also served to further misconceptions about the nature of library work as less complex or skilled.

“I sometimes get the feeling that Bowdoin sees library work as clerical, not intellectual. Even my coworkers who are in paraprofessional positions engage in skilled and specialized work,” one employee wrote.

Left In The Dark

While many employees who spoke with the Orient argued that a market-based compensation study would inherently undervalue the work of library staff, they also pointed out that frustrations were inflamed by poor communication, a lack of transparency and inadequate action on the part of College administration.

When Segal conducted a similar compensation study at Oberlin College, employees tasked with drafting “stripped down” job descriptions received a 58-slide presentation outlining specific tools and methods to do so. This was not done at Bowdoin.

After library staff received letters detailing their new compensation, many turned to one another to decipher the results of the study.

“It was a time when the library staff became very transparent with each other, and it was kind of lovely for a terrible reason,” Shawn Gerwig, a conservation technician at H-L, said.

Library workers created a spreadsheet comparing their wage grades and percentiles, shared detailed notes from meetings with HR and made buttons listing their pay grades. And on May 24, 2024, every staff member present at work signed a letter to library leadership urging immediate action to rectify the inequities caused by the compensation study.

In response to this letter, former Library Director Peter Bae pushed to reevaluate the results of the study for library staff. What followed was a makeshift appeals process, where staff had the chance to edit and resubmit their job descriptions for a second assessment. According to library staff, changes resulting from this reevaluation process were minimal, and in some cases, resulted in no change to employees’ compensation.

“By September of 2024, we [got] an email from [Bae] and HR, saying certain individuals’ grades have been changed.… ‘The problem is solved, we’re moving on.’ And I think for a lot of people that didn’t really sit right,” Barton-Norris said.

“Even though the appeal is done, [and] I’ve been told…, ‘This is the way it’s going to be’. I [still] talk about [the study],” Gerwig said.

Gerwig still shares her pay grade in her email signature and on a button she wears at work.

“I feel like it’s the only thing I can do. I don’t feel like there are really any avenues left. And I want it to be out there,” she said.

What comes next?

Over a year has passed since the conclusion of the compensation study, and many employees’ frustrations still feel fresh.

“I think that there are a lot of fences to be mended.… There’s a lot of work to be done to bring the library back to feel[ing] valued by Academic Affairs,” one employee said.

Some employees were optimistic that new leadership could be the start of this process. At the end of last year, Kat Stefko, who previously led Special Collections and Archives, took on the role of interim director at the Bowdoin Library.

“I hope that [Stefko] will feel empowered to stand up for library needs,” one employee wrote.

Another looming question is that of the library building itself, which is slated for a major overhaul in the coming years. Numerous workers hailed this move as long overdue.

“H-L has leaked since it was built. That building needs to go. It is not healthy to work in,” one worker said.

But others warn that a new building can’t fix everything.

“I think there’s a lot of pressure put on the idea of a new library building that would solve all of the issues [of the wage study], but I think that’s a bad approach because … you can’t change the people just by putting them in a new building,” Barton-Norris said.

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy:

- No hate speech, profanity, disrespectful or threatening comments.

- No personal attacks on reporters.

- Comments must be under 200 words.

- You are strongly encouraged to use a real name or identifier ("Class of '92").

- Any comments made with an email address that does not belong to you will get removed.

So, so, SO glad that this is leaving the library bubble! A very interesting, but important, reality to illuminate, especially given Bowdoin’s primary role as a living capsule of learning. Our librarians are the front lines in connecting us to our passions and goals during our time here at Bowdoin, and I would love to see more administrative appreciation for the scale of their work, not only as intellectual ambassadors, but also as mentors, role models, and experts.

Employees of a $2.9 billion dollar institution have to get food from a food pantry? Shame on Bowdoin.

This is the kind of work I hope to see more of here. Thank you for writing about this.

An important piece of journalism. Well done, Karma. Well done.