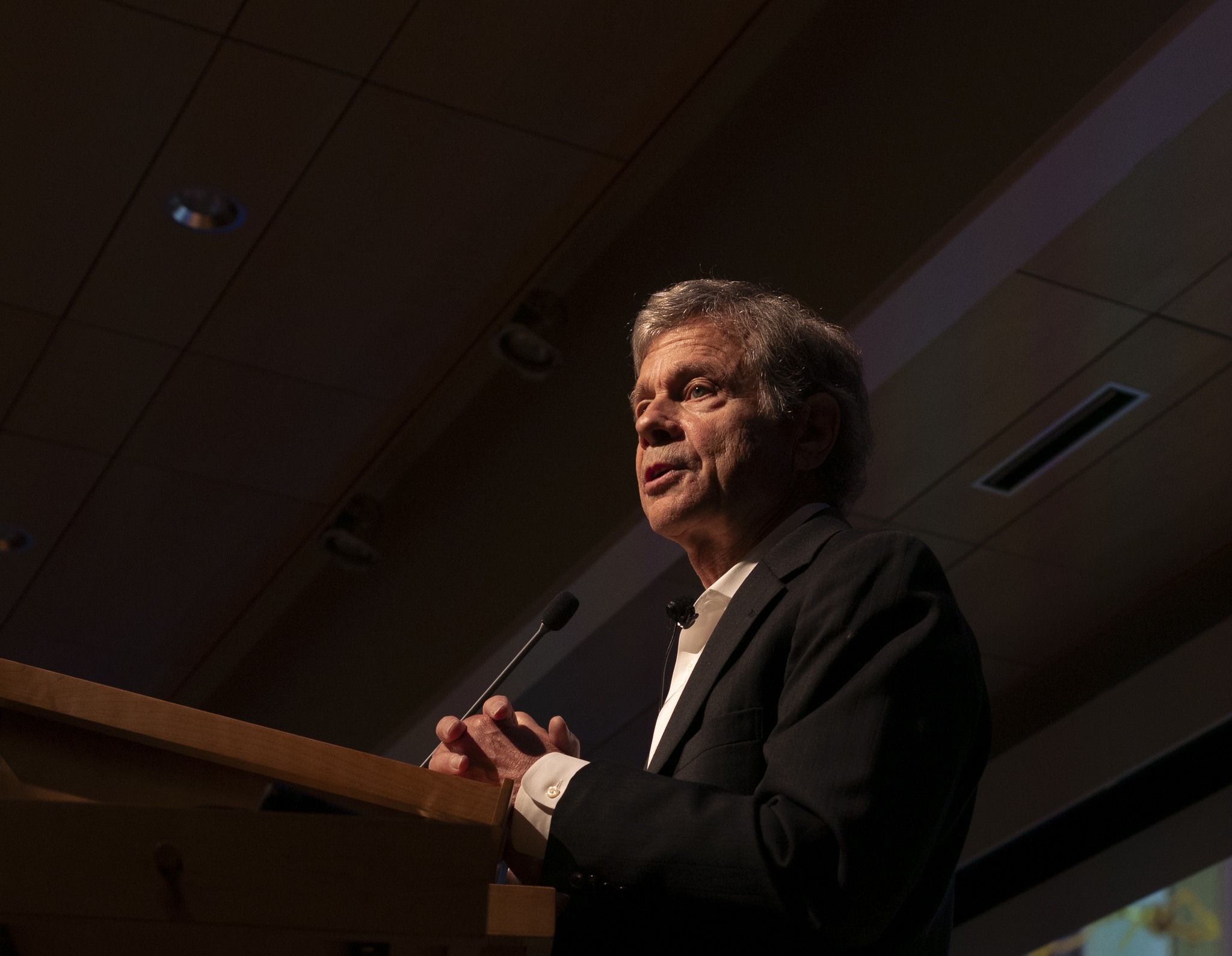

Alan Lightman illuminates the lives, motives and significance of scientists

October 24, 2025

Andrew Shi

Andrew ShiOn Monday, author, academic and scientist Alan Lightman H’05 shared his vision for how science—and scientists—should engage with the world beyond their academic work. Over the hour and a half lecture, which was based on his co-written book “The Shape of Wonder: How Scientists, Think, Work and Live,” Lightman highlighted the life and works of scientists to deconstruct their morals and motivations, hoping to humanize the profession and instill greater trust between the scientific community and the general public. The talk was sponsored by the Kenneth V. Santagata Memorial Lecture Fund, the Donald Zuckert Fund and the Department of Mathematics with assistance from the Hastings Initiative for AI and Humanity.

After an introduction by President Safa Zaki, Lightman highlighted his interactions with scientist Lace Riggs, today a postdoctoral associate at the McGovern Institute for Brain Research at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). Lightman went on to describe how, despite this prestigious position, Riggs was raised in incredibly difficult circumstances.

“[Riggs] and her family were moving from house to house, sometimes expelled within a month because her mother couldn’t pay the rent, and they had to store most of their belongings at a storage facility,” Lightman said. “She was motivated by her own experience watching her family disintegrate due to drug abuse and mental illness.”

Eventually, her life experiences led her toward an interest in the brain, and she received a PhD in neuroscience from the University of Maryland before working at MIT. To shed light on the humanity of Riggs and other scientists, Lightman highlighted her personality and interests both inside and outside of work, illustrated through her living and working spaces.

“In the sitting room, there’s a bookcase containing titles ranging from the fantasy novels of Kelvin Hearne to … Lord of the Rings to Plato’s Republic to various textbooks on biology and neuroscience,” Lightman said.

Next, Lightman contextualized what appears to be a rise in global mistrust of scientists and their institutions.

“Such mistrust, I think, is part of the global populism movement in which scientists are seen as part of the elite establishment, out of touch with ordinary people and often thought to be motivated by political or economic interests,” Lightman said. “A part of this mistrust is driven by disinformation in social media. Another part is the lack of understanding by much of the public on evidence-based critical thinking. When scientists change their recommendations, it’s not because we’re wishy-washy; It’s because new information has become available.”

Lightman expressed how most scientists are driven by a genuine desire to help improve humanity.

“Very few scientists are motivated by political or economic interests. We scientists are mainly motivated to help our societies,” Lightman said. “In the book, we also explore and discuss the nature of evidence-based critical thinking.”

Further, Lightman spoke about scientific advancements that have drastically improved society.

“Today, the fraction of people worldwide living in extreme poverty is nine percent, so 65 percent [living in extreme poverty in the 19th century] decreased to nine percent; So what happened to bring about this astonishing increase in human life and wellbeing? Science and technology—in addition to advances in biology and medicine—the industrial revolutions, beginning in the mid 18th century, vastly increased food production and the creation of goods.”

Attendee Eli Bundy ’27, said he enjoyed the talk’s discussion of evidence-based critical thinking but wished it were more focused on how scientists could engage with the public.

“Because I am a science major and am in science class basically every day…, I take for granted a lot of the stuff he was talking about in terms of evidence-based critical thought and changing your belief if you come across new evidence,” Bundy said. “But I’m a little conflicted about the relationship between the public and scientists. To me, an important way to help people get excited about science is to engage them in a science rather than saying, ‘This is the science that I’ve learned.’”

Meanwhile, Mateo Morales Gómez ’29 said he appreciated the humanity that was brought to the life and work of scientists.

“That [talk] explains the other side about scientists because we usually see scientists [as just people] … who thought about formulas, but these are actually people who have their own lives, their own problems,” Morales Gómez said.

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy: