Be quiet

April 24, 2025

This

piece represents the opinion of the author

.

This

piece represents the opinion of the author

.

Henry Abbott

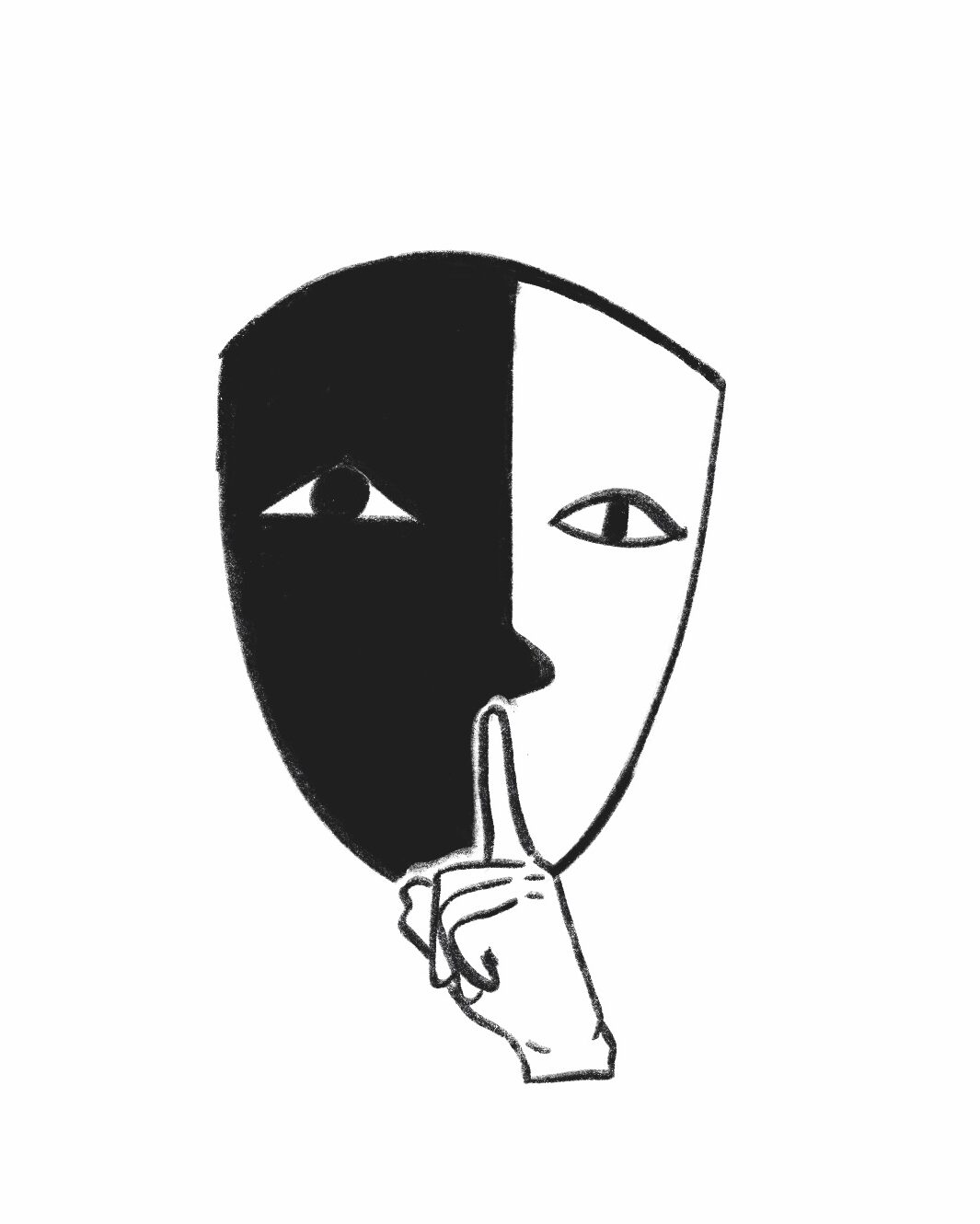

Henry AbbottFor the last seven years, my New Year’s resolution has stayed the same: talk less. This isn’t because I’m a particularly rambunctious interlocutor. In fact, I tend to be one of the quieter ones. My resolution endures because I think that whatever quietism I come by honestly is worth cultivating and enhancing within myself.

My final maxim is a call to cultivate the stillness that only silence provides. It is a challenge to be a more joyful host to our post-industrial world’s leaden barrage of noise. The quietude I propose is not the muffled thrum behind clogged ears but the radical embrace of all noise—an upstairs neighbor’s lumbering gait, the birds’ early evening springtime song and the metronomic beat of the car alarm right outside your apartment. It’s all music. The virtue of being quiet is the virtue of being a good listener. A good listener is a judicious observer.

With the rise of social media came the death of the critic. In an age where the follower is duly followed, an opinion is required, and its dissemination is compulsory evidence. To admit that you simply do not know is to commit yourself to the saccharine simplicity of youth; you are the shell of a fully formed agent. That is, we are a righteously opinionated collective. In our age of information, it seems that there is no longer any excuse to refrain from taking a stance on every crevice of current affairs. And it seems that the assumption that bearing an opinion is itself a virtuous act goes unquestioned. The assumption is that more knowledge is better. But I often don’t know, and I imagine many of you don’t either.

Don’t mistake this call to quiet as one of self-denial—that you are somehow suffering an injustice at your own hand by “being silenced.” Don’t mistake your worth for your output (for the sensory impingements you produce). Your existence isn’t an act of superimposition on your environment. Existence is not additive or reductive; you are already part of the fabric. There is a sense in which noisemaking—opinion professing, mindless chattering, etc.—is a way one can testify to their own worth or even to humanity. It sounds the alarm that I am here, I am alive, I am worth listening to. It is what has fueled the rise in aversive attitudes towards privacy. We have a newfound social policy in soul-bearing, of making yourself human by making yourself relatable to the basest degree. But you have nothing to prove; there is simply nothing to prove. You already are.

We work and toil under a tyranny of voices, and we work and toil to uphold this tyranny. Sangfroid and steely in attitude, we launch tongue twisters into an already violent salvo of discourse—a discourse that first ravages ears and then numbs them completely. When we land ourselves in the position of perennial critic, we lose any need to listen to one another. The more and more auditory material there is to engage with, the more inconsequential our mechanisms of auditory engagement are made and the more we are left disengaged. Our internal dialogues reign and all else can be rendered gratuitous bloviating.

In being quiet, we return to the originally articulated virtue of a principled life: liberation born of discipline. It is a liberty to be found in an indiscriminate embrace of subjugation to one’s untempered environment. The principled ones need not steel themselves against the world; they offer a fervid “Yes!” buoyed amidst the consequences of their radical acceptance with the rigidity of their principles. They are uniquely situated to face the madness, because their path is certain. The quiet one, the one who listens, is the one who is not afraid of what they will hear. They are willing to hear themselves and others think; they are a bigger, sturdier container. Thus, leading a life of principles requires a leap of faith. It requires that you have faith in the maxims, even when they require that you be at ease on precarious ledges, faced with incredulous acceptance amidst blitzkriegs of noise.

I’ll leave you all with the sage lyrics to the White Stripes’ “Little Room”:

“Well, you’re in your little room / And you’re working on something good / But if it’s really good / You’re gonna need a bigger room. And when you’re in the bigger room / You might not know what to do. You might have to think of how you got started / Sitting in your little room.”

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy: