Wabanaki scholar Rebecca Sockbeson talks indigenous education and epistemicide

October 18, 2024

Carolina Weatherall

Carolina WeatherallOn Thursday, professor of education at the University of Alberta, Wabanaki scholar and activist Rebecca Sockbeson gave a talk to Kresge about the importance of Indigenous knowledge mobilization and anti-racist education. The lecture centered around her research on the erasure of Indigenous knowledge in the context of education.

Sockbeson was invited to campus to deliver the Brodie Family Lecture, sponsored by a fund created in 1997 to host an annual speaker in the educational field. The organizer of the event, Professor of Education and Chair of the Education Department Doris Santoro, first heard about Sockbeson from one of her own students in her Education 1101 class.

“I have to say it involved, especially as a white person, doing a lot of listening about how she wanted this visit to go and to do my very best to make this something that would be worthwhile for her and valuable to the Bowdoin community,” Santoro said.

Bringing Sockbeson to campus, according to Santoro, is a part of a wider effort to increase exposure to Indigenous knowledge within the education department.

“In the education department, we’ve been working to include more Wabanaki history and culture into our courses, so I have come across [Sockbeson’s] research before, and I knew that that was something we had not addressed: Indigenous knowledge,” Santoro said. “Indigenous education is something that we have not talked about before, specifically Wabanaki history. Particularly because we are on this land of the Wabanaki, I thought it would be an incredible opportunity for us.”

At the start of her talk, Sockbeson acknowledged her ancestors who were dispossessed and removed from their land—the land that Bowdoin is currently on. Sockbeson and two younger men sang the Mi’kmaq Honor Song, which was envisioned by Mi’kmaq elder and leader George Paul when he got caught in a thunderstorm on his drive back from a Sun Dance in Saskatchewan.

“And what [the Mi’kmaq Honor Song] will do is call in and honor those ancestors.… We’re always asking for guidance and mercy from the Creator to do whatever it is that we’re doing and to be guided and to do it in a better way,” Sockbeson said. “It’s with that that I want to invite you to pray with us, however you pray, and to think those guiding, powerful thoughts, and maybe think about your ancestors if they’re young or old, and honor.”

After singing the Mi’kmaq Honor Song, Sockbeson delved into the issue of the epistemicide against Indigenous knowledge that has occurred through generations. Sockbeson stated that, in 2020, only 17 percent of Indigenous high school students continued onto college, and 13 percent of Indigenous people have a bachelor’s degree or higher.

“It’s a really stunning insight to think about the achievement gap because it’s only growing. And I have changed my vernacular around these matters, because it’s like mainstream education theory will have us think that it’s because there’s a deficiency in the child and American Indian students,” Sockbeson said. “And we know, as American Indians, that is the furthest thing from the truth.”

The deficit theory, as Sockbeson terms, is the assumption that Indigenous people have a fundamental deficiency and that Indigenous people perpetuate the observed achievement gap. But, Sockbeson argues against the deficit theory by acknowledging the systemic educational and socioeconomic barriers Indigenous people face.

Sockbeson also mentioned the deep generational trauma that often pervades the Indigenous community, while making a clear distinction between generational trauma and the idea that Indigenous people have an inherent deficiency that are educational barriers.

“Intergenerational trauma is a reality, a painful reality, but it cannot be the focus of the problem of that widening achievement gap. It just can’t be reduced to, ‘Well, they just have lived through too much trauma,’ or ‘They’re not getting enough culture at school,’” Sockbeson said. “Could the problem ever be that we’re not preparing our teachers adequately—that the system is broken?”

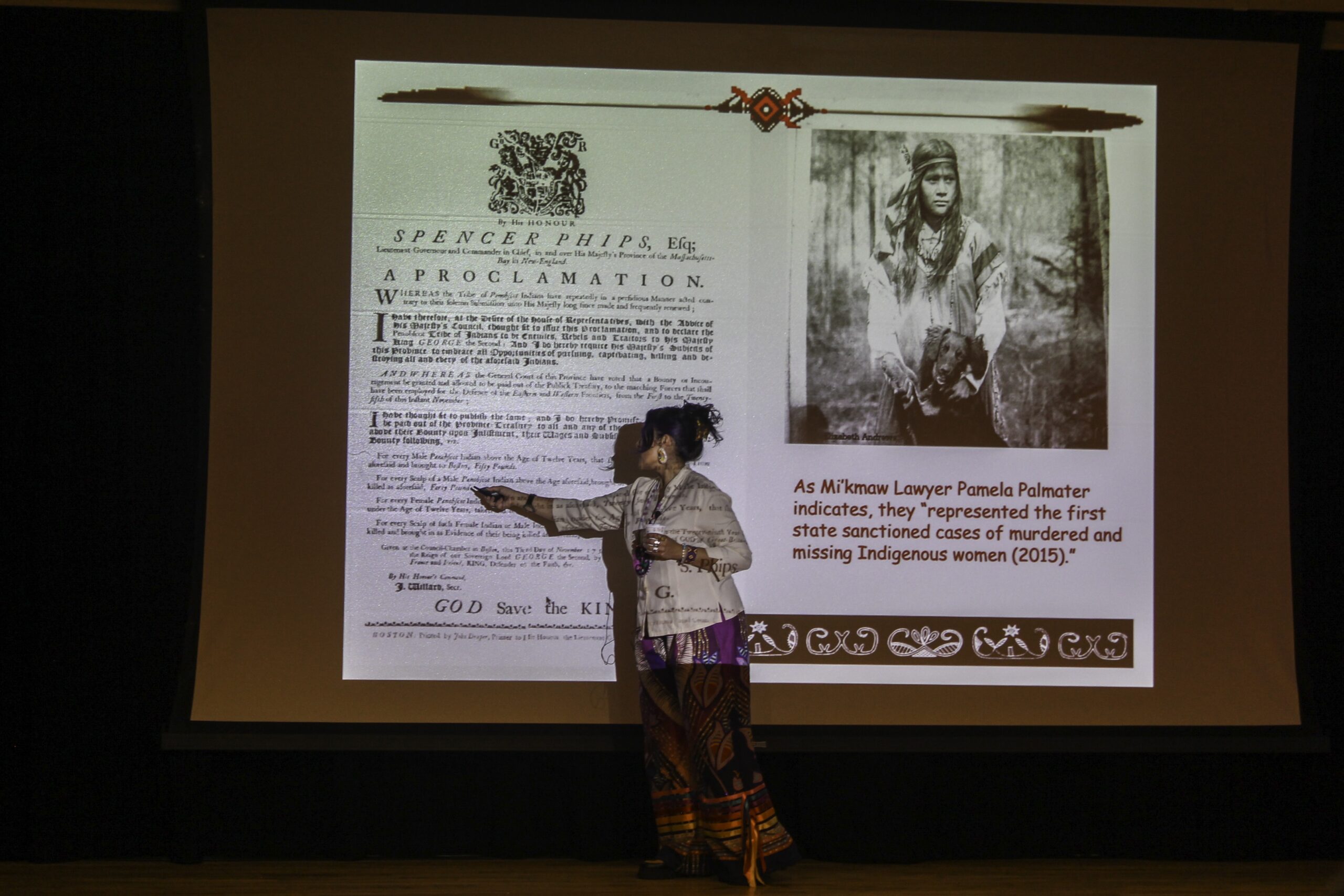

Sockbeson then touched upon Penobscot history and the dispossession of Indigenous people from their land. She said that the number of Wabanaki tribes decreased because of genocide and state-sanctioned violence against Indigenous women, and she specifically pointed out Indigenous land displacement in Maine.

“When we talk about, and in your own land acknowledgement here at Bowdoin, it talks about the painful legacy. It accounts for one of the largest acts of genocide the world’s ever known,” Sockbeson said.

The erasure of Indigenous knowledge is also seen in the epistemicide of Indigenous knowledge.

“For Indigenous epistemology, there was an intention to eradicate our ways of knowing and being. Take the language away from the people, take the ceremony away, take the culture, take the land. Only deal with the men and take the women’s power away. Only make land transactions with men. Take all the power away from women of communities that are matriarchal, ancestrally matriarchal. It’s a very powerful colonial apparatus to take away,” she said.

Sockbeson ended her talk with a note of hope. Even through years of epistemicide, she said Indigenous knowledge has not and will not be erased.

“There was an intention to eradicate by apprehending kids, wrongfully apprehending kids, putting them in Indian residential schools. But it’s important for you to have an image that we are so much more than that,” she said. “And not only have we survived, but we have retained our capacity to love because there was an intention to eradicate that. And so the epistemicide has not been complete.”

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy:

- No hate speech, profanity, disrespectful or threatening comments.

- No personal attacks on reporters.

- Comments must be under 200 words.

- You are strongly encouraged to use a real name or identifier ("Class of '92").

- Any comments made with an email address that does not belong to you will get removed.

Thank you for this important article. It is heartening to see some at Bowdoin engaging in these difficult issues that acknowledge stolen land, genocide and White colonizing attempts to erase Indigenous knowledge. We can’t change the past, but we can begin to heal from it.

Indigenous wisdom and knowledge is especially important today as our world effectively grapples with the urgent problem of the climate emergency – a problem I do not believe will be solved by giant industrial machines sucking carbon out of the air, etc. but via a more nuanced approach that works with the forces of nature. Hence, the importance of seeking the knowledge of cultures that understand this balance.