A history of solar eclipses in totality at Special Collections and Archives

April 12, 2024

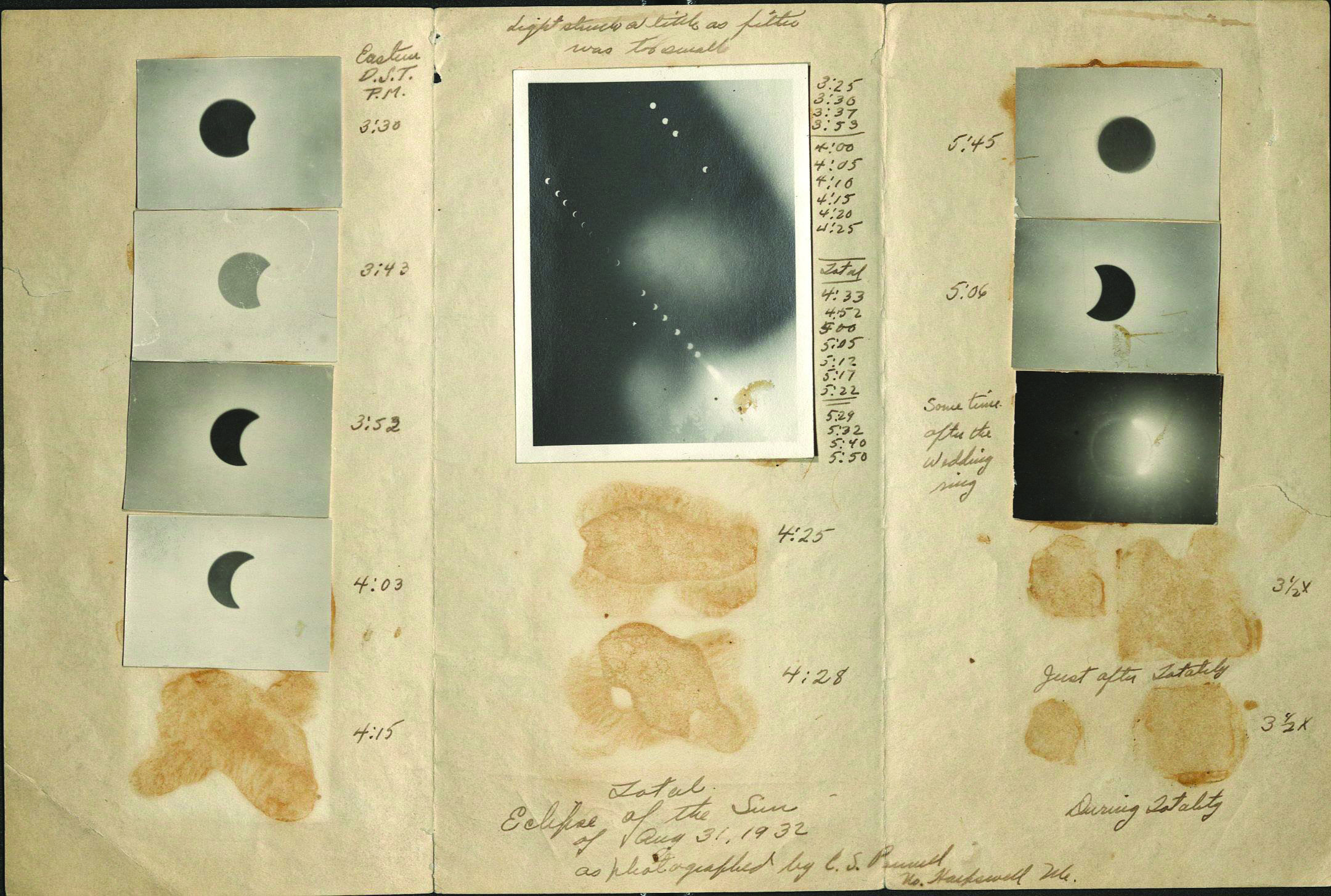

Courtesy of Special Collections and Archives

Courtesy of Special Collections and ArchivesWhile many eclipse-chasers traveled north on Monday, Special Collections and Archives traveled back in time to present an open house on the history of eclipses documented at Bowdoin and beyond.

The idea was conceived by Special Collections Education and Engagement Librarian Marieke Van Der Steenhoven and Director of Special Collections and Archives Kat Stefko. Van Der Steenhoven said that the exhibit stemmed from photographs she found captivating from the 1932 eclipse in Brunswick.

“We used that as the basis and then did a bunch of research broadly around thinking about astronomy—thinking about eclipses and what kind of material we might have,” Van Der Steenhoven said.

The open house consisted of eclipse material from the rare book and manuscript collections in addition to the College’s archives. Items included an Orient article from the 1932 eclipse, solar year calendars designed by artist Priya Pereira and two photo albums documenting solar eclipse exhibitions sponsored by the U.S. government.

“Those 19th-century photo albums of scientific expeditions are really interesting because they show just photographs and labels, but not any of the other information about these scientific expeditions that occurred in 1883 and 1889 that looked at where they all traveled to map the various eclipses,” Van Der Steenhoven said.

Special Collections and Archives also reached out to Assistant Professor of Physics Felicia McBride for input on the exhibit and the pieces selected for it.

“I thought [the open house] was a great idea to think about how eclipses, especially solar eclipses, [were] seen in the past and what kind of material we have from any sort of historical documents, both relating to Bowdoin but also just any other material that was available,” McBride said.

The exhibit’s first visitor was driving up to the path of totality from Philadelphia last weekend, but exited the highway in search of eclipse glasses.

“[He] ended up on the third floor of Bowdoin’s library, secured a pair of eclipse glasses and looked around, and he got super excited,” Van Der Steenhoven said. “What I hope—for the folks that came—is that it was inspiring to think about the eclipse and its role in culture in the past.”

Brunswick saw a solar eclipse at totality in 1932, drawing crowds of local scientists to campus to record data and capture images. Locations in New Hampshire, Vermont, Massachusetts and Canada were also dotted along the path of totality that year.

“On top of a chimney on the Searles Science Building, an observation platform had been constructed,” the Orient reported in the September 28, 1932 edition. “Using their anemometer records and the courses of their pilot balloons, the group predicted a cloudless sky for four-thirty in the afternoon, the time of the totality. The predictions were fulfilled.”

Unfortunately, the story of the 1932 eclipse at Bowdoin is marred by tragedy. George B. Pottle ’32 fell from the roof of the Bowdoin observatory while setting up a prism spectrograph to capture a flash spectrum of the eclipse.

“[Pottle] accidentally fell from the roof and fractured his spine, causing instant paralysis,” the Orient reported in 1932. “Pottle was to have entered the Harvard Graduate School of Science this fall. While at Bowdoin, he was one of the most promising men of his class.”

Photographs taken during the 1932 eclipse bookend its totality, from the characteristic “diamond ring” of light seen shortly before to the narrow crescent visible after. One photograph of totality from the event was showcased on the front page of the September 1932 Bowdoin College bulletin.

The materials produced by scholars observing the eclipse from Bowdoin were supplemented by editions of Harper’s Weekly depicting the 1860 and 1869 eclipses. The first page of the 1860 edition displays a monochrome drawing of the eclipse cutting a path of totality across the Atlantic Ocean. Readers could have used the diagram to determine what degree of totality they could expect to see from their location.

“I find it so fascinating that nowadays everything is computer-programmed and computer drawings, but at the time, everything was handmade. So, it was very beautiful drawings of both the orbital inclination of the moon and how the moon’s orbit changes over time and what the conditions are that are required for an eclipse,” McBride said. “Some of these very technical drawings were super well done.”

Solar eclipses have also been used to prove Albert Einstein’s theory of relativity—one instance of which was documented in a report by astronomer Arthur Eddington, published after the 1919 eclipse viewed in Africa. A second edition of the report was exhibited for visitors on Monday.

“There’s all of these really interesting intersections with astronomy,” Van Der Steenhoven said. “We had that actual second edition of the report that the astronomer, Arthur Eddington, made that proved [the theory of relativity].”

Van Der Steenhoven hopes that the open house inspires and encourages more people to utilize Special Collections and Archives, which is available to anyone, from Brunswick community members to Bowdoin students, faculty and staff.

“I’m always interested in making what we have in Special Collections and Archives more accessible, so making it easy and fun for folks to come in and to touch old books, to engage with historic materials and to really feel empowered to do that,” Van Der Steenhoven said.

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy: