Velcro letting go

February 9, 2024

Amira Oguntoyinbo

Amira OguntoyinboClinginess may not be a desirable trait, but for velcro and for plants, their ability to cling is an asset. The market value of velcro, though, also depends on its ability to let go.

Letting go of things has never been my strong suit. The day I was born, when I was handed into my mothers arms, I grabbed her IV cord with my tiny newborn fist. Concerned that I would yank out the needle, my mom encouraged me to release my grip, but my little fingers would not let go. I had just been released from our nine-months-long umbilical attachment. Had I not let go of enough?

Five years later, I had let go of my mom’s IV, but instead, I clung to my friends. Everyday, when preschool was over, I wailed at my mom the whole way home. I cried because I wanted to stay longer. I demanded playdates to see my friends. More years passed, and I learned to drive myself home, but I still hated saying goodbye to my friends. I lingered at their houses, and then I moped as I drove home.

I tell you stories from my childhood to spare myself the vulnerability of admitting that I still have trouble letting go. Today, I keep clinging and lingering, making myself late to dinner, meetings and social engagements. You will not find me crying to my mom as I walk home from Super Snacks. But I do lie awake in bed at night because I cannot let go of the day I had and the people who filled it. I like holding onto things, and sometimes, holding on pays off.

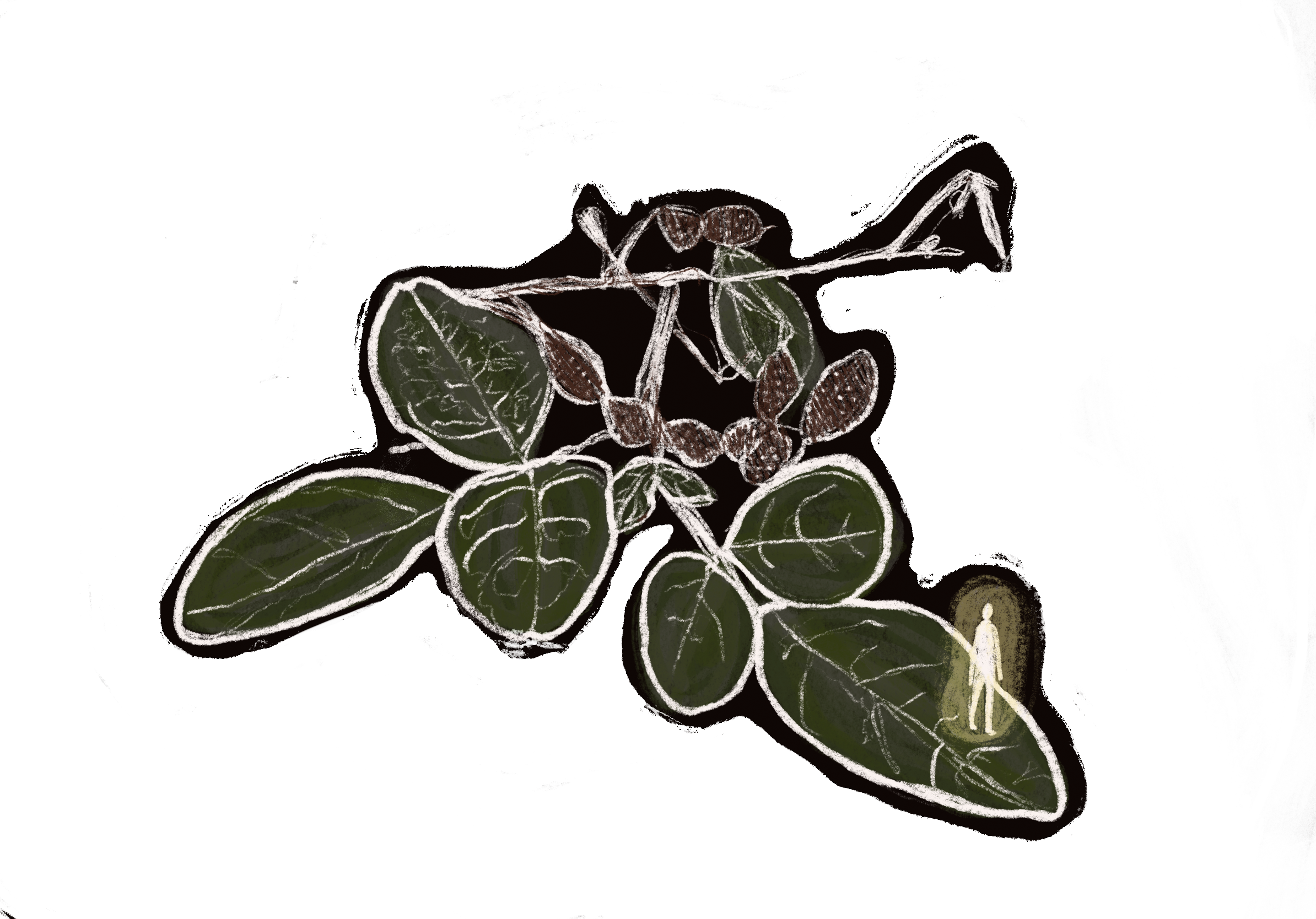

For numerous plant species, holding onto things is how they have made their way in the world. Before they even germinate, clingy seeds grab onto fur, clothing, or skin to disperse themselves. With their burs (the tiny hooks that inspired the invention of velcro), they latch onto animals. By holding on tightly to an animal’s fur, a seed can be dispersed to untapped, fertile ground. Florida Beggarweed, a particularly prolific plant in peanut fields (much to the dismay of peanut farmers), is so clingy it earned the name “Erva d’Amor” (“love herb” in Portuguese). Over millennia, plant species developed burs because clinginess was an adaptive trait—clinginess helped the plants survive and reproduce. Wild grasslands were not the only “survival of the fittest” arena in which clingy burs offered a competitive edge. In a capitalist market, velcro shoes made their way with clinging hooks that mimic the burs on seeds. Their clinginess had economic value. But there is a catch.

Clingy seeds and velcro can let go. If velcro could not be pulled apart, it would be useless, and I would have learned to tie my shoes much sooner. If a seed with burs never comes off of the animal it clings to, it will never fall on fertile ground. It will not fall on any ground at all. In order to latch onto the animal in the first place, the seed has to let go of its parent plant.

If a seed could never let go of its parent, it would be clinging, uselessly, for eternity. If I could never let go of my friends, I would still be a preschooler wailing at her mom. And if I cannot let go at the end of each day, I become a sleepless zombie. If, instead, I can let go of today, I will be able to better grasp tomorrow.

Letting go of the day’s thoughts at night is no easy task. According to the CDC, 1 in 7 adults report having trouble falling asleep on most nights. A variety of relaxation practices are recommended to treat this difficulty. Progressive muscle relaxation (PMR) is one of these techniques. Counterintuitively, PMR requires tensing one’s muscles. Insomnia patients are told to tense and then release their muscles. Focusing on the change from the tensing feeling to the releasing feeling induces relaxation. The change between two states is key, just as it is for velcro. When patients alternate between holding and releasing, they are better able to let go.

With practice every night, I am getting better at letting go of the day’s worries when I put my head on the pillow. On bike rides, too, I am learning to let go. I cannot ride without my hands on the handlebars for long, so I alternate. I hold on, then release, hold on, then release, as if I am practicing PMR. When I do let go, I find myself soaring through the air, arms out, palms open, experiencing newfound freedom. I imagine my newborn self felt a similar joy as she was discovering the dexterity of her little fists—as she learned to grab and release, grab and release.

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy: