First star I see tonight

September 23, 2022

This

piece represents the opinion of the author

.

This

piece represents the opinion of the author

.

Chayma Charifi

Chayma CharifiLooking out my bedroom window, I see a bright light blinking across the dark sky. The sound of an engine rumbles low in the distance.

“Starlight, star bright,” I whisper to myself.

Growing up next to Boston Logan International Airport, there was too much light pollution to see more than the moon and clouds in the night sky. My “stars” were airplanes, departing or landing. Though I knew real stars were hidden in the darkness, to me, stars were as mythical as mermaids or the Loch Ness monster.

Stars have fascinated humans forever. We’ve played connect-the-dots to create constellations. They’re the basis for astrology and a key component of many religions. They’ve guided sailors across seas and oceans. We’ve invented telescopes and satellites to better see them. They’re the subject of countless poems, songs and works of art. Stars may not have the same practical function that they have had in the past, but we yearn to learn more about them nonetheless.

I was five years old when I saw my first star. My extended family went camping on Cape Cod over Memorial Day weekend each year, and it was my first time joining. We sat around the fire pit, bundled in layers because the May nights still got chilly. All of a sudden, my cousin started shouting about a star. I peered deep into the blackness of the night, eager to see this phenomenon. Sure enough, there was a star. My heart sank in disappointment. I thought the star would be much more exciting than a tiny dot. Thus, I went on with my life. The planes continued to glide across the night sky, and the hidden stars slipped my notice.

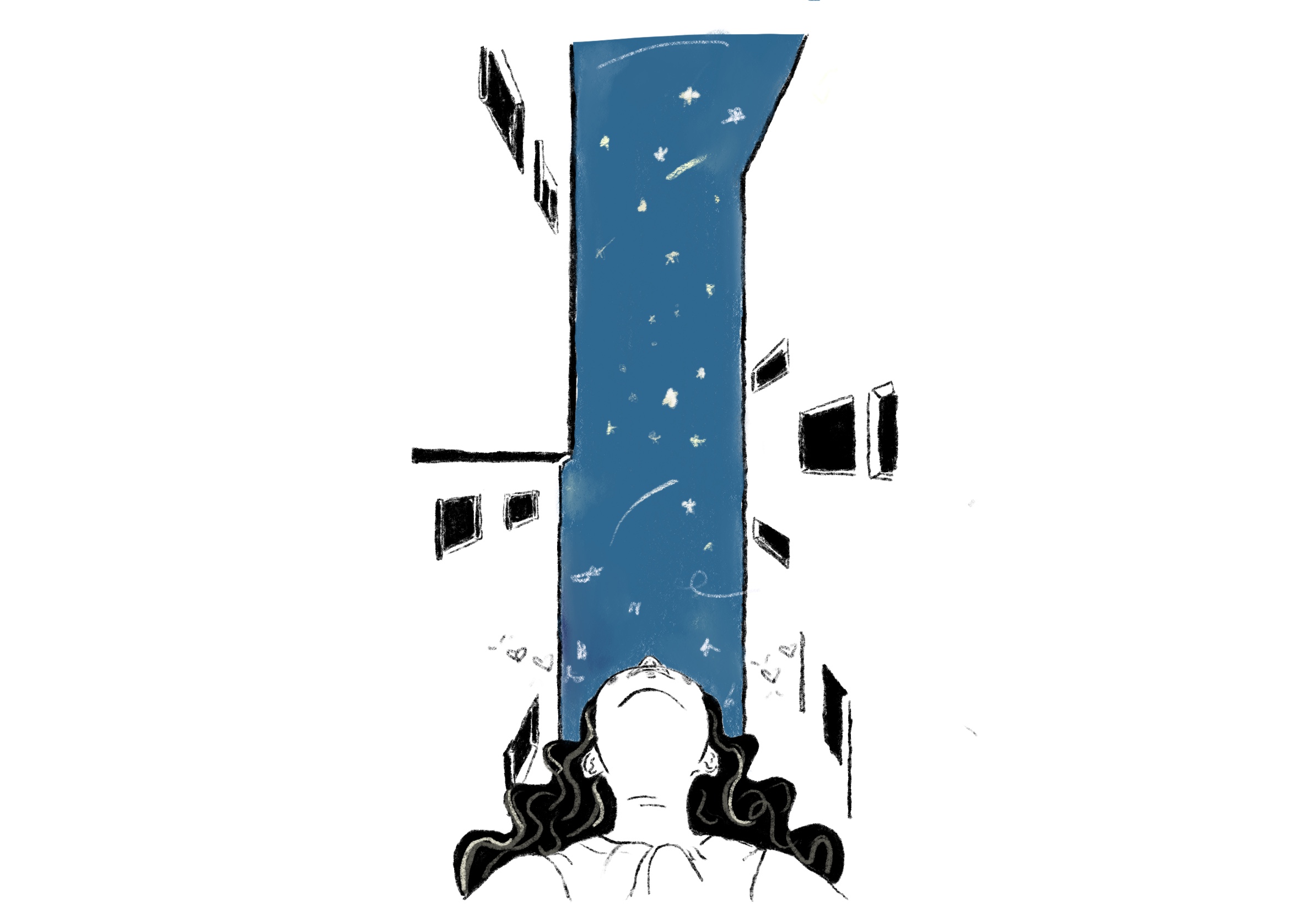

That changed less than a month ago when I really saw stars for the first time. My orientation trip went to North Haven Island, a community about twelve miles east of Rockland. On our last night, there were clear skies, so we decided to drive out to one of the island’s beaches to stargaze. I remember stepping out of the van and looking up at the sky, immediately shocked into stillness. The sky was scattered with stars—so many you could never count them all. I was completely amazed.

Lying down on the beach, we gazed up at the Milky Way. We saw constellations like the Little Dipper, and others we imagined names for. One of my group members taught us all how to notice satellites. After patiently waiting and waiting, we even saw shooting stars. My “shooting star” airplanes from when I was younger paled in comparison to the real deal.

Back in Brunswick, you can’t see as many stars in the night sky (though behind Farley Field House on a clear night can be very impressive). However, I’m still surprised when I look up and see little pinpricks of light in the darkness. And though I know stars are just luminous balls of gas, I appreciate and feel comforted by them.

Most of these stars have been around longer than the Earth, certainly longer than we’ve been around. It’s difficult for me to fully understand how constant they have been to how we’ve grown and adapted as a society. I feel connected to my family back home knowing they have these stars above their heads too, even if they’re hidden by city lights. I think about the generations of Bowdoin students who, just like I, have gazed into the night sky during their first weeks here and silently, even secretly, thought to themselves,

“I wish I may, I wish I might, have the wish I wish tonight.”

Julia Dickinson is a member of the Class of 2026.

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy: