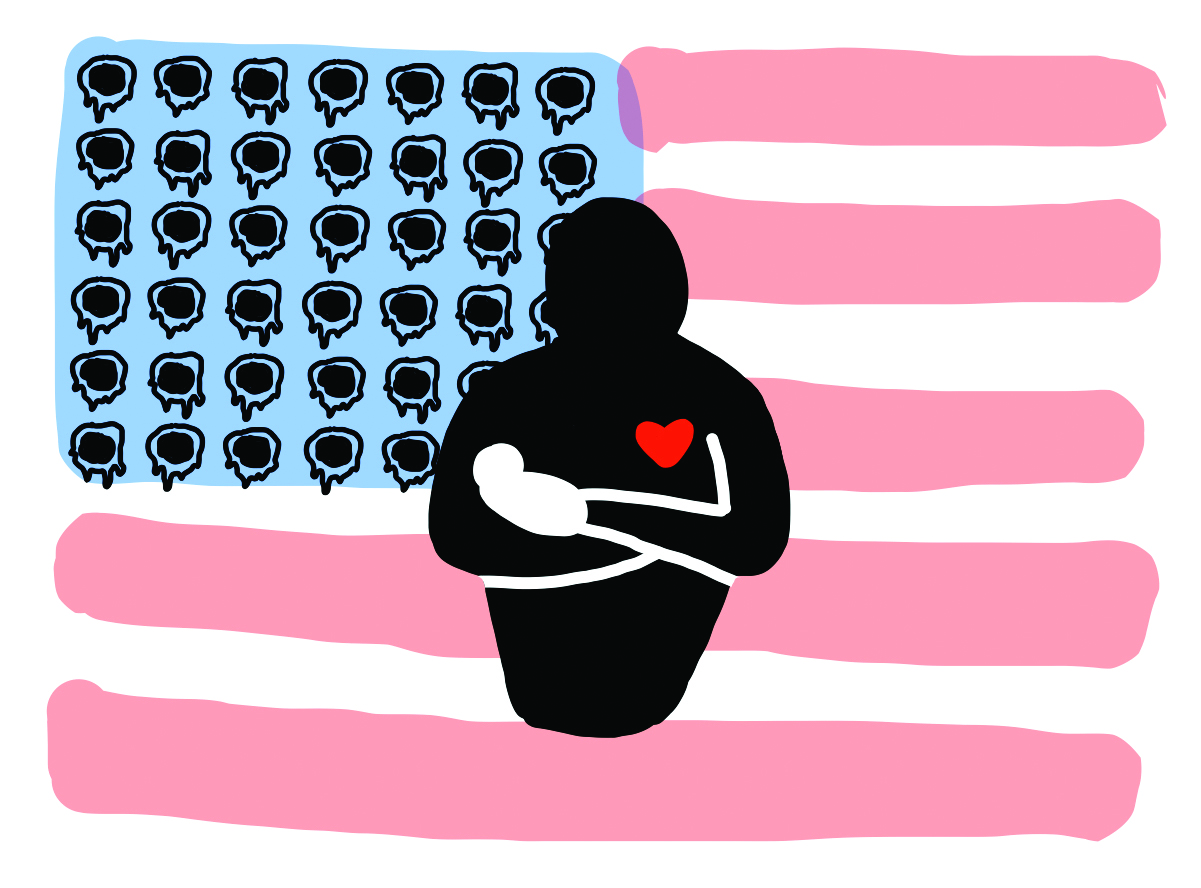

The myth of the absent father

April 16, 2021

This

piece represents the opinion of the author

.

This

piece represents the opinion of the author

.

Nora Sullivan Horner

Nora Sullivan HornerOn Sunday, 10 miles from the courthouse where former Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin is on trial for the murder of George Floyd, Kim Potter, another police officer, shot and killed Daunte Wright.

As he was being pulled over, Wright called his mom to tell her he was getting pulled over because he had air fresheners hanging from his rear view window. Just like George Floyd called for his mom as he struggled to breathe under the knee of Chauvin, Daunte Wright called his mom. Because he knew what was going to happen.

He was unarmed.

His body was left on the street, covered by a white sheet, for hours.

He was a father to one-year-old Daunte Wright Jr..

He was a father.

There is a particular narrative about Black fathers, who are often portrayed as absent and uninvested. This history traces back to slavery, when families were forcefully and frequently separated and rearranged. Slave owners often raped and impregnated enslaved women, leaving enslaved men with children who weren’t biologically their own.

Despite this, as Libra Hilde explores in “Slavery, Fatherhood, and Paternal Duty in African American Communities over the Long Nineteenth Century,” enslaved men were “loving, involved, and emotionally invested in their children … they provided for and protected their families to the best of their ability, provided religious protection, and nurtured their sense of self-worth and identity.”

The false notion of Black men as inadequate fathers persisted for centuries, and in 1965, Patrick Moynihan, under President Lyndon B. Johnson’s administration, wrote a report called “The Negro Family: The Case for National Action.” In it, Moynihan identified widespread poverty among Black families, and he argued that the “steady disintegration of the Negro family structure” was responsible. This victim-blaming tactic gained a lot of traction and remains a pervasive argument for the racial economic inequality that we still see today. President Obama even highlighted the perceived need for Black fathers to take responsibility for their families in a Father’s Day speech in 2008, saying that Black men “have abandoned their responsibilities, acting like boys instead of men … And the foundations of our community are weaker because of it.”

The narrative that Black fathers are irresponsible is in part rooted in traditional ideas of what a two-parent household looks like. While it’s true that, according to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), 70 percent of Black, non-Hispanic children were born to unmarried women in 2013, unmarried doesn’t mean fatherless. As Josh Levs points out in his book “All In,” most Black fathers live with their children—-2.5 million out of 4.2 million. Furthermore, they are actually more involved in their children’s lives than white fathers, according to the same study by the CDC. Compared to fathers of other races, Black fathers who live with their children are more likely to physically care for their young children (bathe, change diapers and feed), and they are more likely to read to their children and help them with homework on a daily basis. Even among those who do not live with their children, Black fathers are still more likely than white fathers to be involved in their children’s’ lives by talking to them about their day and taking them to activities.

It’s worth thinking about the systemic factors at play—if Black family structure is indeed disintegrating, why? Why is a Black child six times more likely to have or have had an incarcerated parent than a white child? Why are Black men twice as likely to be killed by police as white men?

Why won’t Daunte Jr. have a father?

Black fathers have always demonstrated a deep connection and desire to care for their families. It’s the racist, white institutions that have tried so hard to get in the way of that.

Claudette Proctor is a member of the Class of 2021.

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy: