Counseling isn’t enough, turn to institutional change

April 2, 2021

This

piece represents the opinion of the author

.

This

piece represents the opinion of the author

.

Kayla Snyder

Kayla SnyderWhen I was younger, I would slightly bend the pages of the book I was reading and tap them with a pencil to stay focused. This habit of mine occurred often; I would rush through my classwork so I could get back to reading books I was actually interested in. My love for reading led me to a love for libraries. I would walk down the aisles as I tried to find the perfect books to take home, devouring ten at a time and then returning to check out even more. Reading was my favorite pastime, and the characters were easy to understand and connect with. All of their thoughts and emotions were laid out on the page, and though moving around a lot provided me with lots of opportunities to make new friends, books were a constant.

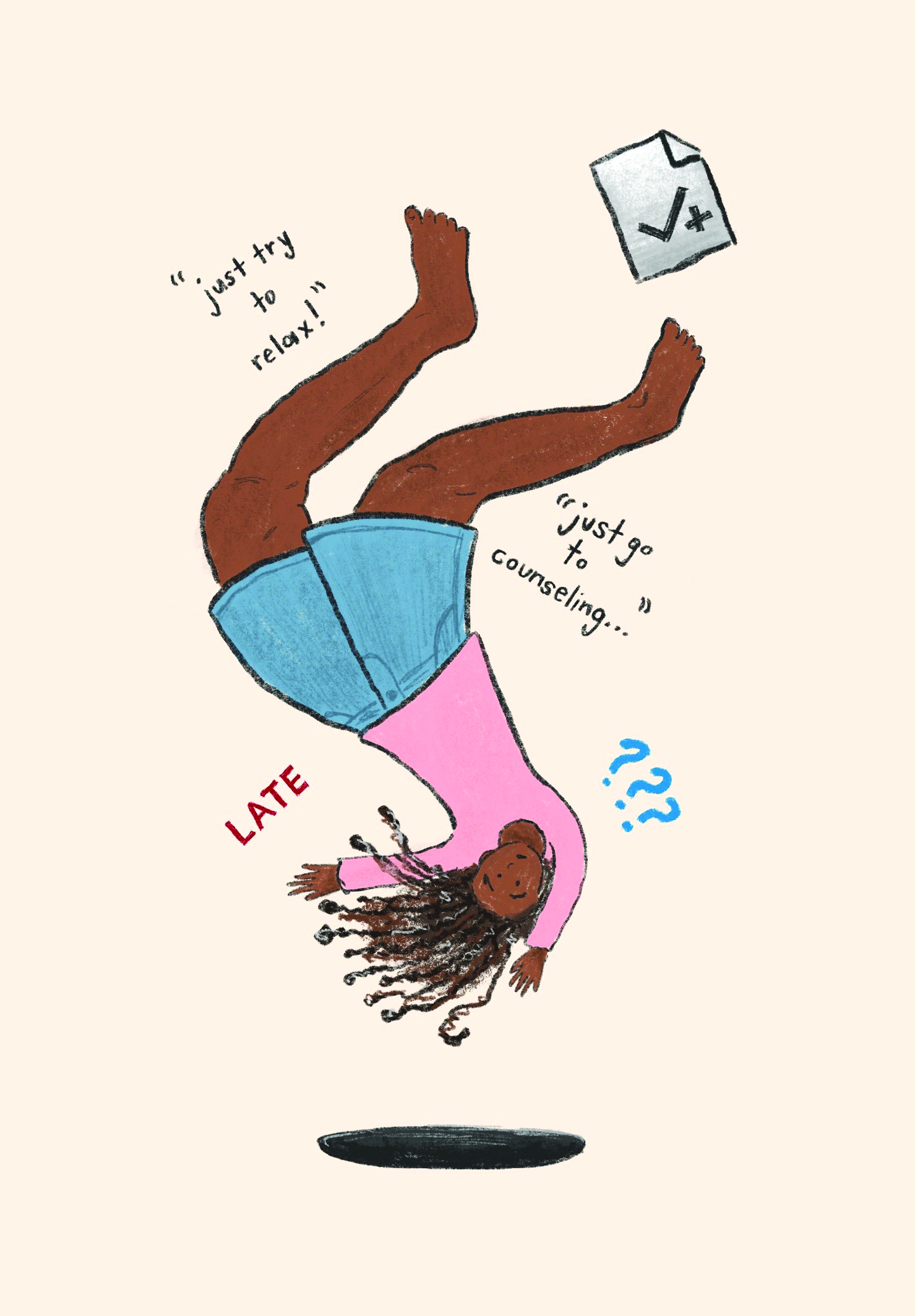

In high school, I was still faring well academically—at least on paper. In reality, I would start assignments late, remembering them at the last minute, and while I managed to turn them in on time, the teachers didn’t know that I was up late the night before trying to produce work I felt would be acceptable. Unless an assignment interested me or was a group assignment, it would fade to the back of my mind. Although being in sports helped me with scheduling my day, ultimately, if I didn’t want to do something, it would get pushed to the last minute.

Then I came to Bowdoin. While I felt prepared academically due to the quality of my public school in northern Virginia and the 4.0 GPA I had managed to achieve, I struggled in my chemistry class and pulled many all nighters trying to turn in papers before my professors woke up. Something wasn’t clicking, and it wasn’t until the end of my first year, when I was packing up my room to go home and still had four papers to finish, that I realized something wasn’t quite right. I knew I was smart; I was at Bowdoin for a reason, right? I knew I was capable and on track to become an amazing doctor; the adults in my life never failed to mention it. But as I sat writing research papers the first few weeks of summer, I started to internalize the thought that maybe I wasn’t that smart after all.

Over this past year, I’ve been reading more about the onset of mental illnesses, disabilities and poor coping mechanisms once students make it to college. The stress and competition at schools like Bowdoin forces students to either stay caught up or get left behind and suffer the consequences of academic probation or a year-long mental health medical leave. While accommodations are offered if you can prove you need them after rigorous testing (ADHD screening in Brunswick takes six hours), some of us don’t have access to them. For others, like me, who have been told their whole lives they are smart because they were able to get exemplary marks in this neoliberal system of ours, the thought that I may not be neurotypical takes a lot longer to process, and thus so does figuring out my options.

Black women are often left behind when it comes to healthcare. With the highest maternal mortality rates, it’s not surprising that we also constitute the highest percentage of people over the age of 16 who are diagnosed with ADHD, according to a UK study. Although I am still waiting for my official diagnosis, I’ve been prescribed medicine to address symptoms of ADHD. But as I mentioned before, without a formal diagnosis, my professors aren’t required to offer me extensions (and even if I had a formal diagnosis, most professors don’t respect students enough to remember to acknowledge their accommodations). In a school filled with students worried about grades and getting into top graduate programs and receiving the highest praise, it can be extremely daunting to push for institutional changes that would not only benefit neurodiverse students, but would release a lot of neurotypical students from the bondage of functional alcoholism and other harmful coping mechanisms prevalent on college campuses like ours.

Late-stage capitalism—a term dating back to 30s and 40s European sociologist circles—asks you to take a “mental health moment” before diving right back into a workload that prevents you from organizing a strike, waking up without worrying about how a late assignment will cause you to be deducted of a grade and into a lucrative job on Wall Street where you can snort your days away. The “breaks” we’ve had during the hardest year of our lives have been inadequate in healing us from the harms of hyperproductivity, and I know that professors haven’t been faring well either.

“Safiya, I know everyone on campus is miserable and burnt out, but that’s just the way things are!” Who says we have to continue the cycle of misery because those who came before us went through it? If we are to have a better future, we must imagine it and make it a reality ourselves. Imagine a campus where there are more classes like my Intro to Africana class, where we were allowed to curate our own grades, doing various assignments worth different points to get the grade we wanted, utilizing videos, songs, discussion sections and posts, lectures, papers and projects to create a well-rounded and fully accessible class for people of all learning styles? Imagine if we did away with penalties for late work and looked to readings that were easy to understand rather than overly convoluted and indigestible? K-12 schools in Maine have already begun to shift to a proficiency-based learning model where the focus is more on “do you understand the material” rather than “can you regurgitate this information in an academically elitist way.”

TW: Suicide

I don’t know how much more of this students will be able to take; a first-year student at Yale recently took her life, and while we can never know the particulars of her situation, going to an elite liberal arts institution takes a heavy toll on the body and mind. I myself was unsure if I would be able to graduate on time had I not been able to take much-needed time off when I studied abroad. Factoring in the pandemic on top of things that are going on back home and the uncertainty of our futures, it’s a miracle people show up to class at all. It is time to rethink higher education beyond adding more counselors and yoga sessions. The energy on campus has been extremely draining lately, and now more than ever we need to change the way we do higher education.

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy:

- No hate speech, profanity, disrespectful or threatening comments.

- No personal attacks on reporters.

- Comments must be under 200 words.

- You are strongly encouraged to use a real name or identifier ("Class of '92").

- Any comments made with an email address that does not belong to you will get removed.

“ readings that were easy to understand rather than overly convoluted and indigestible” seems to refer to academic papers. While certainly technical at times, I’m not sure how we become scholars without close study of scholarship. Who is doing the ‘translating’ would be concerning – why can’t we bask in the originals? Shouldn’t we be pushed to tackle with great ideas written by experts in their fields?

“we were allowed to curate our own grades, doing various assignments worth different points to get the grade we wanted”

I’m not sure I understand. Wouldn’t everyone want an A? There is a learning and growth that comes from professors pushing us outside of what appeared to be limits. While the author may be correct that grade-fixation is detrimental to student health, grades serve as a flawed but objective learning of our own standing and mastery of material.

1. Here we have to be honest: who is considered scholarly and worthy of their knowledge being studied? what is considered knowledge? Overwhelmingly these papers are written for people who have already reached a certain level in their field and effectively gatekeeps this knowledge from people who don’t come from high schools that thought them to read texts like the ones we ar assigned here.

2. Although I would rather abolish grades completely, most Bowdoin students are strongly against that, so I figured just go the Harvard route and advocate from grade inflation and as long as you understand the material and show the professor you are able to make connections (regardless of how wordy and convoluted your paper is) then yes everyone would get As. Also grades are never objective when we have professors who ask for writing samples from non-white students because they aren’t sure if they can “handle the demands of the course.” Professors are humans too, meaning they have bias and that bias will always show in their grades.

Among other things, the purpose of college is to prepare one for living in the real world; a place where deadlines and expectations exist and penalties for failing to meet them. When you fail to pay your bills on time, there are consequences. The credit rating agency doesn’t care that your mail wasn’t forwarded on time by the post office or that you had limited resources and had to pick and choose which bill to pay. When you fail to renew your cars registration or let your auto insurance policy lapse, there are consequences. You may get a ticket for the expired registration or suffer the loss of your uninsured vehicle without the ability to replace it. You say, “Imagine if we did away with penalties for late work…” – what exactly are you learning when you receive no penalty for failing to meet a deadline? After school in your career, the boss won’t care that you have ADHD, various stresses, or other personal demands on your time. You either do what you’re supposed to do when you’re supposed to do it or you don’t and suffer the consequences. That’s life-college is the time to learn that lesson.