Door to door, day by day

We followed student organizers as the first primaries unfolded.

February 14, 2020

Ann Basu

Ann BasuSaturday, February 1—Rochester, N.H.

The calluses first appeared around day 12 in Sioux City, Iowa, says Penny Mack ’22.

“You knock like two doors, and the calluses are already coming back,” she says, making a fist with her right hand, her knocking hand. Other canvassing casualties include Mack’s phone (which fell and cracked on an icy doorstep while she was searching for a door hanger) and her gloves. The real pros, she says, avoid calluses by knocking with a tennis ball.

Mack is one of the leaders of Bowdoin For Warren, the campus group organizing for the Massachusetts senator’s presidential campaign. This weekend, she coordinated a group of seven students, all first years and sophomores, to canvas for Elizabeth Warren, making the hour-and-a-half trip to spend six hours knocking doors on a Saturday.

“I think New Hampshire’s going to be big for Warren,” says Leif Maynard ’23 during the drive to New Hampshire. He canvassed during the last presidential race in 2016, but three of the students had never canvassed before, and the other two got their start a few weeks prior with Bowdoin for Warren.

One of them is Emilia Majersik ’22, who said she saw Mack’s Instagram posts from Iowa, where she spent two weeks interning for the Warren campaign over winter break.

Ann Basu

Ann Basu“If she can spend two weeks in Iowa, I can spend three Saturdays,” Majersik says.

Warren is polling at around 13 percent in New Hampshire today, and this weekend’s push is about reminding people to vote, even if they haven’t committed to a candidate.

Armed with clipboards and door hangers, the students split into pairs (except Maynard, the most experienced canvasser, who goes alone) to conquer ‘lists’ of houses across Rochester—a city of about 30,000—of previous Democrat voters or registered Democrats, information obtained from public voter registration rolls and fed into MiniVAN, an app the canvassers use to keep track of their progress and report back to the campaign.

Ben Allen ’23, another leader of Bowdoin For Warren, goes with Mack. This is his first time canvassing, and he is pumped. He decided to get involved after a friend said he didn’t believe the U.S. would see a woman president in the next 10 years.

“I was like, I’ll prove you wrong, fella,” he laughs, though the sentiment is real. “And then I saw her talk, and I thought, alright, I made the best decision.”

Ann Basu

Ann BasuMack and Allen feed off one another’s enthusiasm, staying motivated as they go from house to house, despite getting few responses; Mack and Allen knock on over three dozen doors this morning but interact with only a handful of people.

“Even on a good day, it’s like 40 percent,” says Mack of the response rate, not dejectedly but matter-of-factly.

After a re-energizing lunch at Taco Bell, the canvassers head back to the campaign’s Rochester office—located in the basement of a 1970s office building—to pick up another list for a different part of town. The morning’s ward was strictly suburban, with modest one-story or split-level homes. The afternoon’s ward is more rural and woodsy, with homes further apart.

Even though fewer people answer the door in the afternoon than in the morning, Mack and Majersik keep the conversation positive.

“If you think about how many hours you spend just to talk to X [number of] people, it’s kind of crazy. But at the same time, I know it’s the most effective thing you can do,” Majersik says.

“I know it can feel like you didn’t do a lot, but it actually means so much,” adds Mack. “You’re more helpful than you might feel.”

Monday, February 3—MacMillan House

Courtesy of Bowdoin for Bernie

Courtesy of Bowdoin for BernieIt’s just after 8 p.m., and in the state of Iowa, the first caucuses are beginning. Thirteen hundred miles away, at a Bowdoin for Bernie launch party in the living room of MacMillan House, tensions are high as students await the results.

There are around 40 people crowded in the room. Students introduce themselves, sharing their hopes and worries for the election. For many, Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders offers a vision of a new hope in American politics, for which the Iowa caucuses are the first test for this vision’s success in 2020.

“I don’t think it was before Bernie came into the mainstream for most of us that I cared much about national politics,” says Micah Wilson ’22, one of the leaders of the group. “I think I considered myself political, but there wasn’t really someone until Bernie that got me excited.”

Iowa is crucial for building a national support base in a presidential election, but for Livia Kunins-Berkowitz ’22, who began organizing for Sanders after working with Maine People’s Alliance last summer, much of the reward of organizing comes from building community.

“No matter what happens tonight, we built a nice Bernie community here, and people are passionate and excited,” Kunins-Berkowitz says.

As the night goes on, however, the optimism begins to fade and confusion takes its place as CNN reports inconsistencies in voting logs and delegate allocation.

Around midnight, Wilson, whose laptop is being used for the projector, decides to reclaim his computer and call it a night. Others follow, grumbling their frustrations, and head home.

Tuesday, February 4

Results are released at 5 p.m., although they’re anything but conclusive. It’s a narrow victory for Pete Buttigieg, the former mayor of South Bend, Ind., who was awarded 13 delegates. Sanders is close behind with 12, and Warren comes in third with eight. Sanders, however, wins the popular vote by a margin of greater than 2,000 votes.

Wednesday, February 5—On campus

Justin Ko ’22 has been involved in volunteer coordinating for businessman Andrew Yang, a relatively low-polling candidate best known for his proposal of a universal basic income for all Americans. For Ko, the Iowa results pose more questions than answers.

“People think [Yang] only got 1 percent of the vote,” says Ko, who is known around campus for hanging up #YangGang posters in Smith Union. “In reality, that result is because of the archaic rules of the caucuses. We actually got over 6 percent of the vote in the first round. And we’re expected to do a lot better in New Hampshire.”

Ann Basu

Ann BasuThursday, February 6—On campus

For Kunins-Berkowitz, frustrations have only increased since Monday night. Many news outlets as well as the Democratic National Committee (DNC) are celebrating Buttigieg as the winner, despite his very narrow delegate lead and Sanders’ popular vote victory.

“It’s really disappointing,” Kunins-Berkowitz says. “I think I knew that people didn’t like Bernie in the DNC, but I think I trusted the process, and maybe that was naive. Now I’m losing trust in the process.”

But like Ko, Kunins-Berkowitz remains optimistic.

“I think [Sanders] has a really good chance in New Hampshire,” she says.

Saturday, February 8—Dover, N.H.The Sanders field office in Dover, N.H., is in a house with a few Bernie signs in the windows nestled between a natural foods store and a house adorned with two large Donald Trump flags.

Inside, the office is bustling with energy: around 25 Bowdoin students shuffle in at 9 a.m. for a day of canvassing and are greeted enthusiastically by volunteers and canvassers from across the east coast.

Isaac, a volunteer organizer wearing a “Rights and Democracy” sweatshirt, leads a brief orientation for new canvassers. They’ll mostly be talking to people who already support Sanders, he says. With only three days until the New Hampshire primary, it’s all about inspiring people to go to the polls. And, he adds, he doesn’t expect anyone to be an expert on Sanders’ policy; instead, explain why you’re supporting Sanders.

Wilson, an experienced canvasser both in his hometown of Cambridge, Mass., and, as of two weeks ago, in Dover, has this technique down. At each house, he talks about how, as a student, he’s inspired by Sanders’ plan for free public college and debt forgiveness before asking voters what issues matter to them.

Before long, it’s time for round two in Somersworth, a small city 10 minutes from Dover, which proves to be a more difficult canvassing job. It’s mostly apartments, many of which have doors that are impossible to reach from the outside.

Nevertheless, hopes remain high.

“I’m optimistic,” Wilson says on the way back to campus.

Saturday, February 8—Hampton, N.H.

Ann Basu

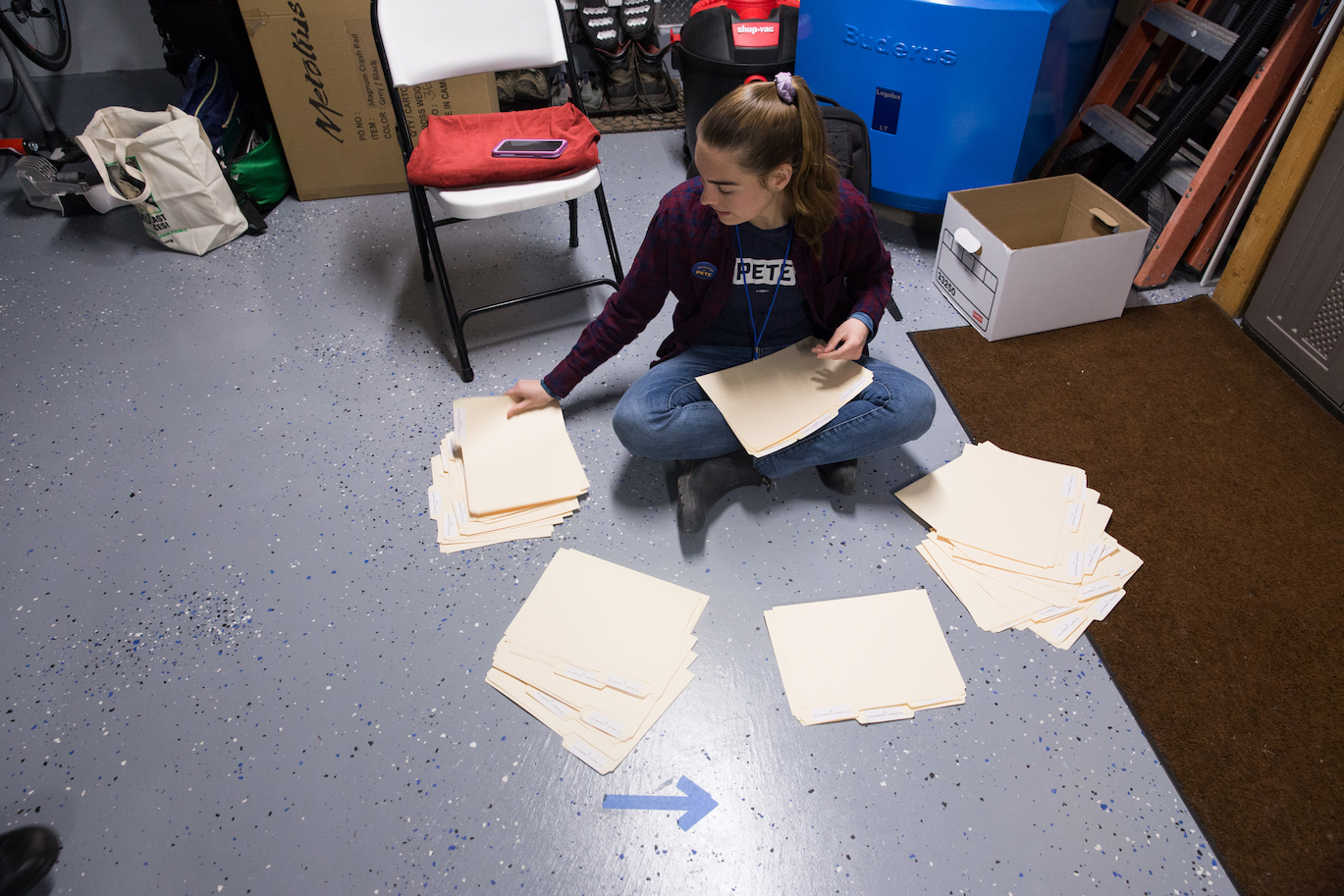

Ann BasuElise Hocking ’22 has set up camp in a volunteer’s garage in the New Hampshire town of Hampton, about 20 minutes from Dover. She sits on the floor with canvassers’ folders all around her and sorts them. Inspirational posters line the walls, and “Win the Era” is written in blue painter’s tape on the floor.

There’s no time to revel in Buttigieg’s strong finish in the Iowa caucus. Bowdoin for Pete left campus at 6:30 a.m. this morning to arrive for its last-minute canvassing efforts ahead of the primary on Tuesday.

Chas Burton-Callegari ’20 and Will deBruynKops ’20 are knocking doors across town. Like the Bernie canvassers, they are focusing on voters who have already indicated interest in Buttigieg, Burton-Callegari says.

One woman invites them inside.

“A week and a half ago I told a guy from Amy [Klobuchar]’s campaign that I would vote for the last person who showed up here,” she says, half joking. Seriously now, she says, “Beating Trump is number one.”

“I’m so upset with Trump, I don’t know where to begin,” she says. What bothers her the most is the current president’s behavior, his dishonesty and fear-mongering, which, she explains, desperate people have glommed onto.

“It’s all about rage,” she says. “[People] turn on others who they perceive to be taking [things] away from them: immigrants, other poor people.”

She doesn’t think that some candidates’ proposals—like total debt forgiveness—will alleviate the divisiveness Trump inspires.

“I did have a major issue, back when this all started: stop saying you’re going to pay off everybody’s college,” she says. “Cut it out; nobody wants to hear that. That’s not going to get us any votes.”

Many other voters agree with her, deBruynKops says, describing a recent townhall for Buttigieg.

“The only thing everyone in line could agree on was that the last thing they ever wanted to do was pay for other people’s college and forgive everyone’s loans,” deBruynKops says.

Ann Basu

Ann Basu“That’s the difference with Pete,” Burton-Callegari continues. “He said one thing to close the debate yesterday, which was, ‘I’m trying to be someone who … doesn’t subtract, but someone who adds.’ And that’s basically what we need: someone to bring more people into our tent.”

The woman is still not convinced. “Any idea how Buttigieg is doing in other states?” she asks.

“A poll just came out in Iowa where Pete took the lead—” Burton-Callegari begins, but she cuts him off: “Yeah, it’s point-one percent.”

Unfazed, Burton-Callegari continues, “Well, he’s taken a lot of votes from Biden and Warren in this state.” That’s important, he says, because bigger states with more delegates like California are coming up soon, and they’ll be watching New Hampshire closely.

After a few more thank yous and a final offer to use the restroom, deBruynKops and Burton-Callegari depart. Though it’s not typical to be invited in, Burton-Callegari says three people have done so today, even though the canvassers are advised to avoid longer conversations.

“Obviously we’re going to engage in a discussion about the things they care about and the things we care about, but a lot of undecided voters are going to decide the day they’re at the polls,” deBruynKops says. “What we want is [for] them to have a memory of two nice young people coming out here and sacrificing their Saturday afternoon to care about someone.”

They both have their own reasons for getting involved in the race—for deBruynKops it’s climate change, for Burton-Callegari, foreign policy—but they agree on why they’re backing Buttigieg.

“It was hard after the Iowa caucus, when, especially on Twitter, people were like, Pete was a cheater and all that, and that negativity is not what we need within the Democratic party right now,” deBruynKops says. “And that’s why I really appreciated Bernie last night on the debate stage. The first thing he said was a message to his supporters saying, we really need to unify around whatever candidate wins because—”

“It’s so much bigger,” Burton-Callegari finishes.

Tuesday, February 11

The results from New Hampshire are much clearer than Iowa. Sanders wins the popular vote again and splits delegates evenly with Buttigieg, nine to nine. Senator Amy Klobuchar of Minnesota surges since the Friday night debate, picking up a close third place finish with nearly 20 percent of the vote and six delegates, while Warren comes in fourth. The field also shrinks, as three candidates drop out: Senator Michael Bennet P’23 of Colorado, former Massachusetts governor Deval Patrick and Yang.

Wednesday, February 12—On campus

Ko is disappointed about Yang dropping out, but, he admits, he’s not surprised.

“I knew it was coming,” he says. “I was holding on to a sliver of hope that [Yang] would do decently well in New Hampshire, enough to continue on all the way through Super Tuesday and the rest of the early states. That clearly didn’t happen. We underperformed this time.”

Ann Basu

Ann BasuThursday, February 13—On campus

The New Hampshire results bode well for the Bowdoin for Bernie campaign.

“I think it’s a win,” Wilson says. “I think it’s decisive, which is what we want after something as disastrous and upsetting as Iowa.”

“So many people put in so much time to New Hampshire and making it happen,” he adds. “And it’s cool to see the counties that we canvassed winning by like 30 points.”

Going forward, the Bowdoin for Bernie group is planning a phone bank, especially for Nevada, the next state to caucus on February 22. They’ll also be canvassing in the Brunswick area leading up to the Maine primary on March 3, super Tuesday. Mostly, though, they’re focusing on friend-to-friend organizing, an informal way of reaching people within their own social networks.

Hocking, of Bowdoin for Buttigieg, says the mayor’s performance in the first two states seemed to encourage supporters at Bowdoin to approach her.

“Over the course of the Iowa and New Hampshire primaries I’ve found there are way more Pete supporters than I knew on campus,” she says.

Mack skipped class on Tuesday to be in New Hampshire with the Warren staffers. After a month of spending every weekend there, knocking on doors and building calluses, seeing the crowds outside the polls felt rewarding, even if the final result wasn’t what she was hoping for.

“I was kind of bummed out Tuesday night, and then I sent a text to my organizer at 1 [a.m.] and was like, ‘O.K., what can I do this weekend?’” she says. “I’m not saying that Bernie and Pete and Amy aren’t going to be the nominee, but I think we’ve still got a long fight ahead of us.”

Ann Basu

Ann BasuAre you undecided, overwhelmed or confused about the elections this year? The Orient would love to hear from you. Contact us via Facebook, Twitter or email at orient@bowdoin.edu.

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy:

- No hate speech, profanity, disrespectful or threatening comments.

- No personal attacks on reporters.

- Comments must be under 200 words.

- You are strongly encouraged to use a real name or identifier ("Class of '92").

- Any comments made with an email address that does not belong to you will get removed.

Go Bowdoin for Warren!