Be wary of an inclusive status quo

January 31, 2020

This

piece represents the opinion of the author

.

This

piece represents the opinion of the author

.

A few weeks after the start of the new year, Johns Hopkins University (JHU) announced it would be ceasing the long-held history of legacy admissions at the institution. President of the Baltimore school, Ron Daniels, boldly announced that reserving legacy slots had been “impairing [its] ability to educate qualified and promising students from all backgrounds and to help launch them up the social ladder.” JHU’s decision comes during a time when Americans are becoming increasingly cynical about democratic institutions being stacked against them.

Eliminating legacy admissions doesn’t substantially threaten Johns Hopkins’ bottom line, but it does signal to other elite colleges that meaningful change is most effective in the form of sacrifices: win-lose compromises where moneyed interests give up some of their hold on the tug-of-war rope. With this new policy, JHU can better deliver on the promises we make as a liberal-democratic society: that anyone with enough steam and brilliance can climb themselves and their family into the American Dream. In a way, the call to abolish legacy flies in the face of the preeminent neo-liberal thinking that flinches at the idea that institutions might need to work against the (very few) wealthy in order to uplift the (very many) suffering.

What happened at Johns Hopkins was more-or-less inevitable. While venerable, it falls predictably in line with the institutional left’s 21st century narrative of inclusivity and diversity. The way I see it, it is only a matter of time before this becomes commonplace and the antiquated tradition of legacy admits falls away because it simply makes so little sense. Legacy-admitted students are three times more likely to be wealthy and white than non-legacy students. Its very existence erodes the idea of meritocracy and is inconsistent with the values that modern universities preach.

The reason legacy admission still exists in most elite colleges today is that it narrowly falls into the utilitarian logic that private colleges need to operate like businesses, and it carries with it an air of patronizing charity. When students from more affluent backgrounds pay full tuition, low-income and minority students can receive grants and scholarships to be able to attend. The enterprise gets to feel fine about unfairly admitting students based on the accident of family ties, especially if it brings in more donation money to direct towards scholarships and attract more diversity. It’s wrong, but just palatable enough. Everybody wins … sort of.

I am not entirely convinced that inclusion—while vital in forming a free and equal society—is the be-all, end-all of justice; rather, it is only the first step in addressing a deeper systemic problem. Inclusion is not enough and in many ways serves to masquerade the part of the process by which social and political power maintains and legitimizes itself by appealing to liberal sentiments of diversity. JHU may have made it easier for underrepresented students to attend, but it hasn’t done anything to ensure more of those students graduate without crippling debt—that would really hurt its bottom line. It hasn’t done anything towards reforming the system that allows a disproportionate number of applicants to have needed to be wealthy in the first place to have had access to better schools and SAT tutors to be qualified.

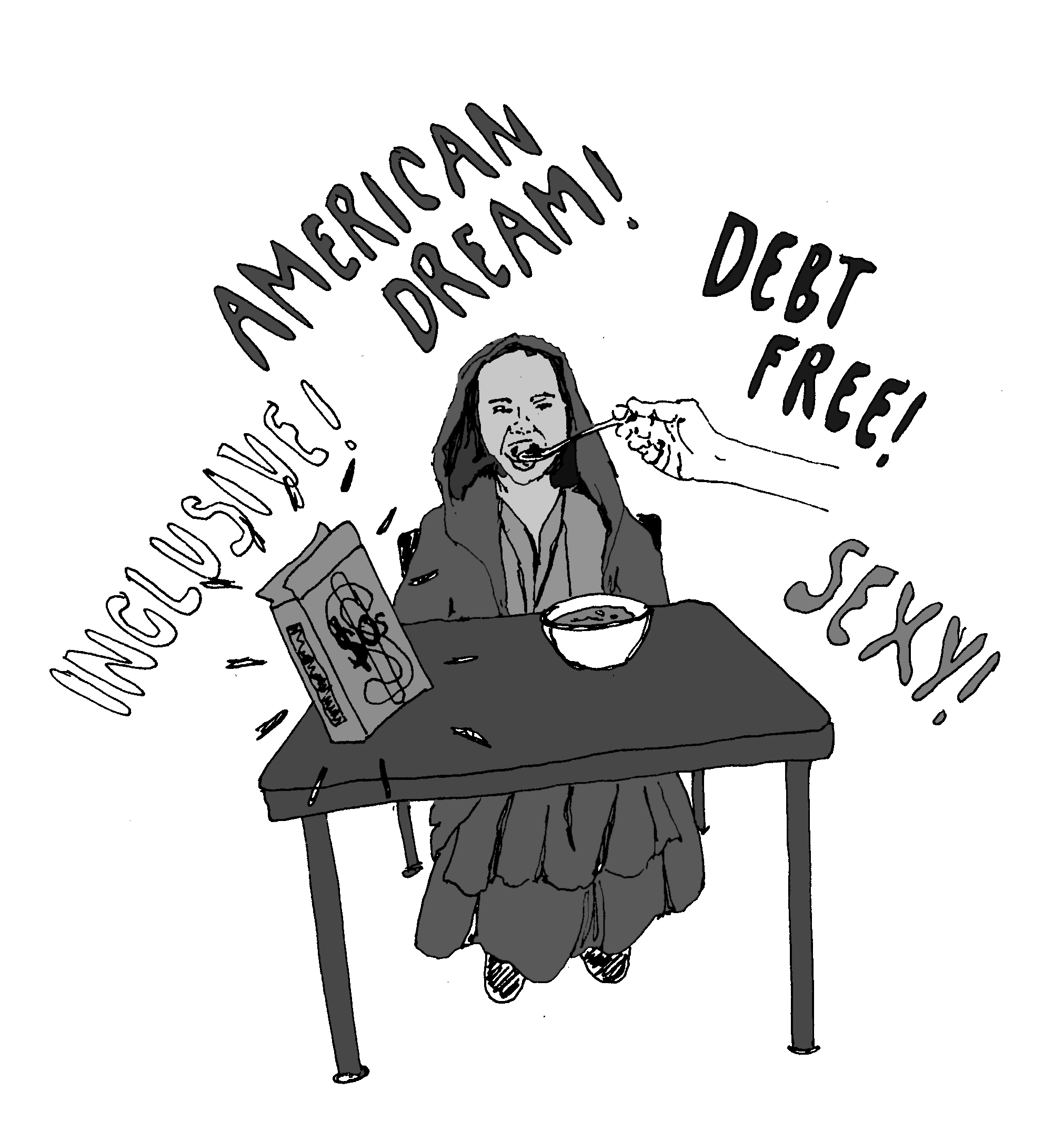

Banks, unicorn tech companies and elite consultancy firms do the same thing in their HR departments: they streamline low-income and marginalized minorities into the hiring pipeline and thus wash their hands clean of historic (and current) exploitation of those marginalized people in the first place. They roll out the red carpet typical of the equal opportunity employers of the plutocrat class, the springboard programs and networking events, the skills-training workshops and networking dinners, the high salaries and the glamorous urban lifestyles. Rarely are these prospective traders, analysts and programmers reminded of the wild-fire gentrification that financial institutions fuel or the income volatility pushed by the profit-maximizing consultancy firms or the dismantling of labor union laws by tech companies like Uber. They somehow make income inequality seem sexy to the underrepresented and the talented.

More inclusive, sure, but private colleges, as well as banks, simultaneously design and profit from fixtures of inequality. Colleges and banks together are responsible for the $1.46 trillion in education debt, which has delayed homeownership in younger generations of borrowers by an estimated seven years. The average graduate accumulates over $40,000 in public and private loans (a conservative estimate). The financial burden affects struggling communities disproportionately: 86.8 percent of black students borrow federal loans to pay for attendance at four-year colleges, compared to 59.9 percent of white students. Post-graduation monthly fees for these loans can reach $600 a month, making it painfully difficult to save for the future—especially if a good chunk of your money goes to supporting your family.

Institutions that tout equality and social justice have established a system of sky-rocketing college sticker prices, insufficient financial aid packages, predatory loan rates, historically flat-lining graduating salaries and dwindling job benefits. These factors only serve to reinforce power structures by making upward mobility virtually impossible. Low-income and middle-class students end up feeling like idiots for following their dreams, voluntarily entering into debt peonage like a 17th century indentured servant after being fed fairytales by college recruitment offices about the affordability of the college experience.

Institutions make the rules that shape interests and ideas, set the incentives, make some things possible and others not. As many students at elite universities and colleges like Bowdoin are being fashioned into the technocrats and functionaries of the status quo, coerced and guided not purely by intellectual curiosity but by the salaries that can buy their freedom from debt bondage, it’s important that we remain awake to the reality that these elite institutions that preach equality don’t do all that much alleviating of inequality. If this neo-liberal, inclusionary status quo persists, we may produce a more diverse cohort of millionaires (and billionaires), but we will certainly not end up with less poverty.

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy: