Golz lecturer discusses women’s role in Indian history

October 25, 2019

Diego Velasquez

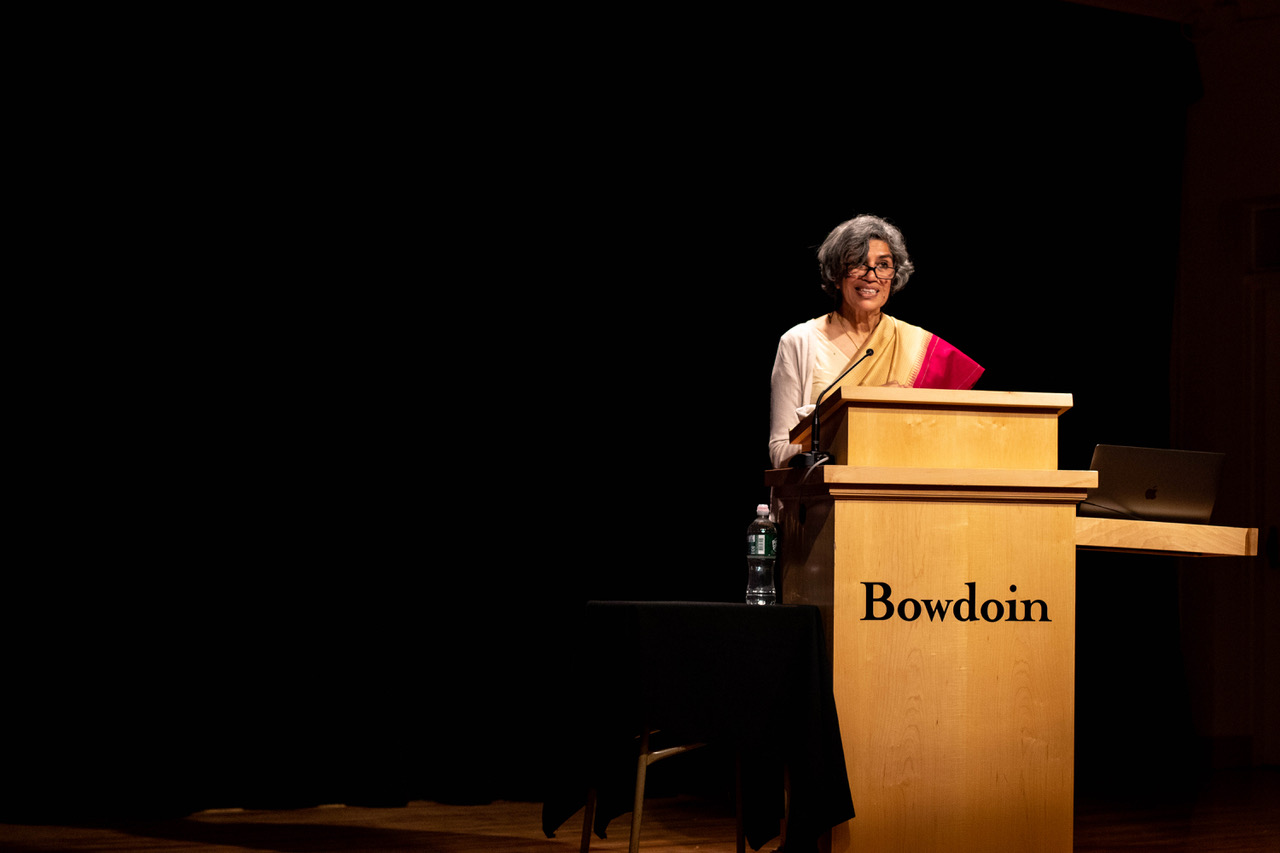

Diego VelasquezHow do historians interpret the surprising presence of ordinary women in the historical archive?

Janaki Nair, professor at the Centre for Historical Studies at Jawaharlal Nehru University in New Delhi, India, addressed this question on Tuesday at the Alfred E. Golz Memorial Lecture titled “Inheritance of Loss: Women’s Wills and Female Personhood.”

In her lecture, Nair told the story of a debt owed to a banker family and the efforts to claim it by its women inheritors, before it was ultimately converted into public charity.

In 1845, banker Damodar Dass of Mysore loaned money to the Maharaja Krishnaraja Wodeyar III, going unpaid for over 70 years. Nair discussed the four female family members’ claims to the unpaid debt and the legal and bureaucratic challenges they faced in their attempt to recover it. These stories reveal a complex framework of laws pertaining to women’s rights and the creation of a new moral order at a time when India was becoming into a modern bureaucratic state.

The story of women’s inheritance that Nair presents speaks to the importance of using archival research to read beyond the official language or legal documents and courtroom speeches to understand the experiences of women.

“Our circumscribed task may be to hear in the interstices of official reports, in the fragmentary speech of the courtroom, the exercises of choice, however vulnerable and the displays of female solidarities, however doomed,” said Nair. “These small voices of history must be made to yield their potential to disturb the univocality of statist discourse and recover for the women whose lives have been involuntarily collided with authority, a place that was not intended for them.”

The traces of the women Nair describes can be found in the archives only because of their failure to produce male heirs. Their personhood, Nair explained, is difficult to recover.

“Sandwiched between the intents of the colonial, princely state and the patriarchal structure of the feudal family, we’re allowed small glimpses in the rips and tears of the fabric of the law from the personhood of women,” Nair said. “The determined effort of the state to deny them these claims forged them into the tortured fragments of our archive.”

In her introduction to the lecture, Associate Professor of History and Asian Studies Rachel Sturman remarked on Nair’s advocacy for intellectual freedom under India’s current right-wing government, which has campaigned against universities, intellectuals and the free press.

“In the context of increasing repression and intimidation, Professor Nair has been a prominent voice fighting for intellectual freedom and for broad economic and social justice and political rights that seem so precarious at present,” said Sturman.

Sturman, who organized Nair’s visit to campus, has followed her scholarship after first reading her work in graduate school. After meeting Nair at a conference in Delhi five years ago, Sturman knew she wanted to invite Nair to Bowdoin.

Sturman thinks that while the lecture might have been challenging to folllow for some students unfamiliar with the topic, it was still an interesting opportunity to understand the legal rights of Indian women in the 19th century.

“This is a context of British colonialism but where the British didn’t rule directly … it’s this very interesting combination of colonial logics and very strong modernizing logics and ideas about what kinds of rights women should have and debates about what kinds of rights women should have and where modernity is identified for the British, in particular, with problematizing women’s rights but not necessarily giving women rights,” said Sturman.

Earlier in the day, Nair visited Sturman’s seminar, “A History of Human Rights,” and discussed contemporary women’s rights debates in India. Sturman believes that this experience was valuable for her students.

“I think it’s useful for students to be exposed to different styles of academia. This is an example of Indian academia and Indian intellectual work and an opportunity for students to think about how the question of women’s rights or the question of human rights … appear within an Indian context and for an Indian academic,” said Sturman. “We expect things to translate in a way that is automatic, that human rights or women’s rights has a kind of immediate readability universally, but even the concept itself gets interpreted differently in different academic contexts.”

Nina McKay contributed to this report.

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy: