Presidents build their legacy—literally

May 3, 2019

Courtesy of the George J. Mitchell Department of Special Collections & Archives

Courtesy of the George J. Mitchell Department of Special Collections & ArchivesEven a cursory glance around campus reveals the ways in which the College has changed since its founding. Buildings, in a range of architectural styles across various time periods, reflect not only the College’s evolution, but also the changes in its leadership. Bowdoin’s presidents have left a range of legacies, both physically and ideologically.

Various presidents brought sweeping changes to the campus’s appearance during their tenures. Many iconic Bowdoin buildings were constructed during William DeWitt Hyde’s presidency between 1885 and 1917, including Hubbard Hall, Sargent Gym, Searles Science Building and the Walker Art Building. Hyde left a clear mark on campus with these additions and the progress they boded for Bowdoin’s status as a premier liberal arts college in New England.

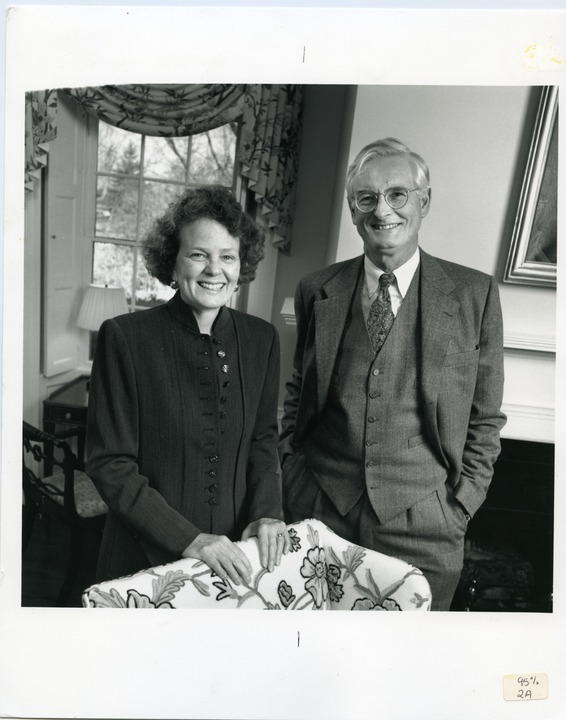

In 1990, nearly 100 years after Hyde entered the presidency, Robert H. Edwards was inaugurated, during a time when the College was struggling financially, functionally and socially. Among other problems were cumbersome governance by two Boards and low first-year enrollment.

As Edwards tackled these problems, his wife Blythe Bickel Edwards sought to use architecture to reverse a “dragging” campus culture.

“[Edwards] actually said to me when he was approached about Bowdoin, I can’t do this alone,” Bickel Edwards recalled in an interview this week. “And my response, given some of the experiences I had in other places—particularly at the boarding school where I was the wife of a headmaster—was, ‘I will help, but I have to be recognized in some capacity as a freestanding individual.’”

Instead of a title or even an office, she asked for her own health insurance and benefits—and she received them. Bickel Edwards then joined several faculty committees responsible for planning new construction, whose members soon disbanded and told her, “you do it yourself.”

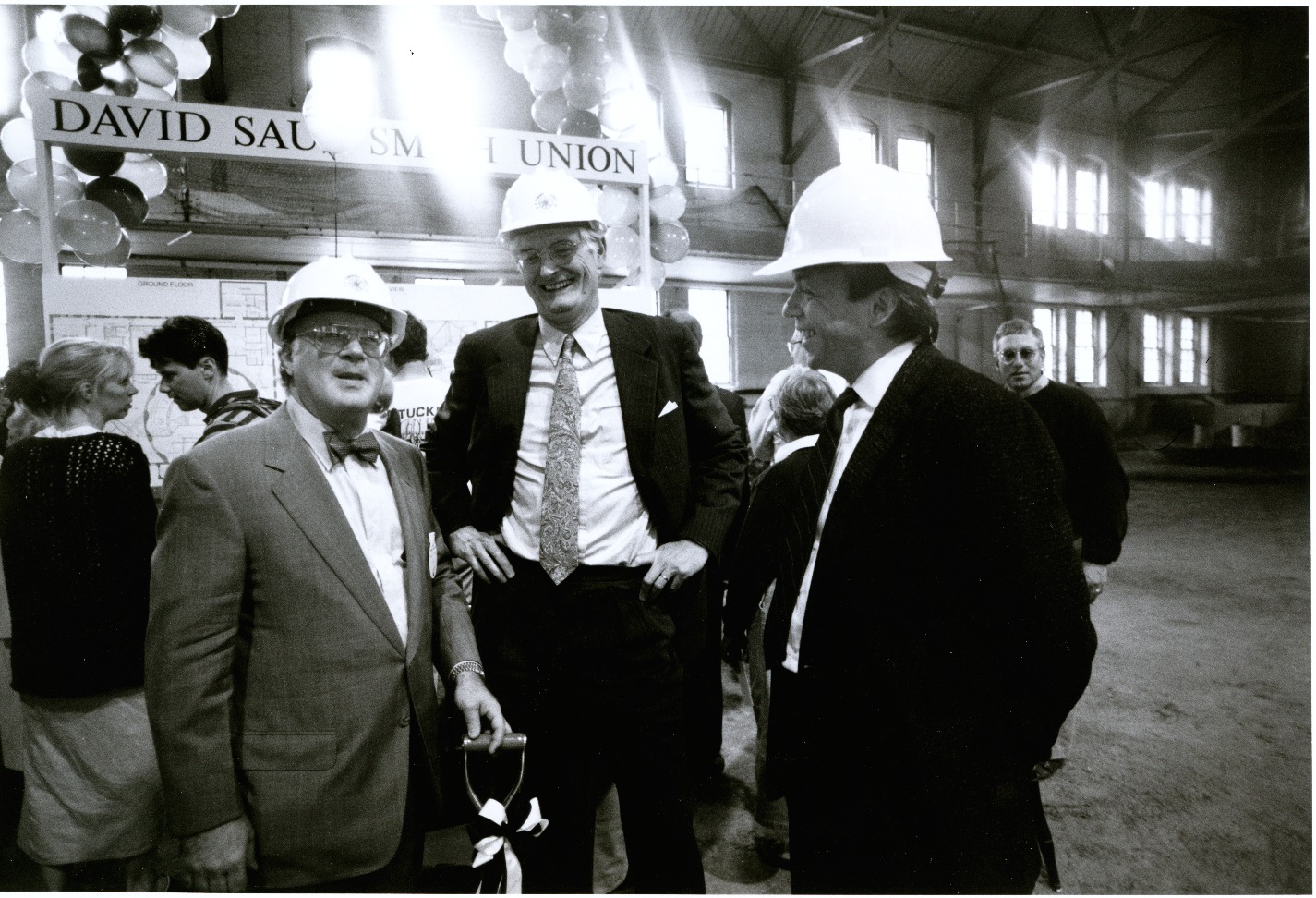

Bickel Edwards felt she had been given a unique opportunity to shape not only the outward appearance of campus, but also how students, faculty and staff perceived the College. She had taken architecture courses in college and had worked in different offices at several other educational institutions, including Amherst and Harvard, where she oversaw married student housing. But at Bowdoin, she managed major projects including the transformation of Smith Union, an expansion of Thorne Hall, the renovation of Searles and the construction of Studzinski Recital Hall.

Courtesy of the George J. Mitchell Department of Special Collections & Archives

Courtesy of the George J. Mitchell Department of Special Collections & Archives“I think the spaces that have been renovated or newly built are reflecting back to students and faculty that they are people to be respected, that they should respect themselves and should see themselves at a serious and prestigious college,” said Bickel Edwards during an interview in 2000, in the last academic year of Edwards’ presidency. “I notice a difference in the behavior of people in those spaces. They come into [Thorne] Hall, and they feel respected and that they are being treated like adults. They speak to you, they address you head on. That was not what we encountered when we first came.”

The opening of the Robert H. and Blythe Bickel Edwards Center for Art and Dance in 2013 recognized not only the couple’s commitment to improving academic and artistic facilities during their time here—the photography labs used to be underneath the pool, they told me—but also continued their tradition of physically and mentally building up the College.

“If we were remembered for anything, it would be along those lines, that we laid our rock on the cairn to make the College stronger,” said Edwards. “We found a place which, quite honestly, was not as strong as we felt the bones of the place were, and we hope that what we did was to build muscle and strength, and when we left, we had done that bit of substantive help to a great historical institution.”

Continuing the tradition of naming buildings after influential presidents, President Clayton Rose announced in December that he planned to name a new academic building in honor of his predecessor, Barry Mills ’72.

“It was totally a surprise,” Mills said. “I was overwhelmed and honored, and that’s the extent of my involvement.”

Plans for the construction of a new academic building were already in place, but Rose suggested naming the building after Mills. The name will have to be officially approved by the Board of Trustees at its meeting next week, but since Rose informed the campus of the plans for Mills Hall via email in January, the decision is as good as made.

“The idea to have a building that memorializes the work that he did struck me as a very good idea,” said Rose.

During his tenure as president, Mills greatly expanded the College’s financial aid offerings, introducing a no-loan initiative in 2008 and steadfastly defending the College’s need-blind admissions policy. He also helped increase Bowdoin’s diversity across ethnic, religious and socioeconomic lines. These effects are felt at Bowdoin, if still as a work in progress.

“It’s not unusual to consider ways of celebrating and memorializing presidents who have done a wonderful job,” Rose said.

Consequently, most—10 out of 14—of Bowdoin’s past presidents have something on campus named after them. Appleton, Chamberlain and Hyde halls are dorms named for Bowdoin’s second, sixth and seventh presidents respectively. With the McKeen Center for the Common Good, the name of Bowdoin’s first president, Joseph McKeen, is inextricably linked to an emphasis on public service. Sills Hall houses various academic departments, including Romance Languages and Literatures and Cinema Studies, and is named for Bowdoin’s longest-serving president. And Greason Pool honors the College’s twelfth president, A. Leroy Greason.

But what about the other four? One would be hard pressed to find the names of William Allen, Leonard Woods Jr., Samuel Harris and Willard F. Enteman outside of the Bowdoin archives.

The case of Enteman, the eleventh president, is particularly notable given its recency. Enteman only served as president for two years before his resignation, from 1978 to 1980. Though the details are largely shrouded in mystery, as the records from his presidency are sealed until five years after his death, it is clear that Enteman did not get along with other higher-ups. Before resigning, Enteman demanded that the vice president for development and the chair of the Board of Trustees both resign as well.

Enteman arrived at Bowdoin fresh from a philosophy professorship at Union College, and soon after beginning his tenure created two committees: one to investigate gender discrimination in Bowdoin’s fraternities and another to consider divesting the endowment from companies associated with apartheid South Africa. Though he was not able to see his goals through in his short time at Bowdoin, the changes Enteman pushed for were reconsidered, and in a few cases implemented, soon after his departure.

John Branch ’16 wrote a Talk of the Quad for the Orient in April of his senior year, when divestment from fossil fuels was still a hot-button topic on campus, after hearing about this little-mentioned president. Titled “The Old Boys didn’t like it,” the article detailed the Enteman controversy and called on the Bowdoin community to consider the ways the College’s presidents are remembered, and what for.

“The decision to name one building after any one person happens on an individual basis, but collectively, they’re an important part of the way that institutional memory functions at a place like Bowdoin,” Branch wrote. “A name attached to a part of Bowdoin’s physical landscape is not an endorsement of every facet of that person’s character, but it is an indication that the namesake is part of a group that made a significant contribution to Bowdoin’s past.”

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy: