Caught on tape: Pete Seeger’s 1960 visit to Bowdoin

April 26, 2019

Pete Seeger stood on the stage of Pickard Theater in front of a single microphone. He picked the strings of his signature long-neck banjo and whistled a gentle harmony, his foot tapping out the beat. After a minute, he stopped playing and began to explain the history of the long-neck banjo and the folk music he played on it. It was March 13, 1960, and a crowd of Bowdoin students sat in the audience, unsure of what to expect from the music lesson.

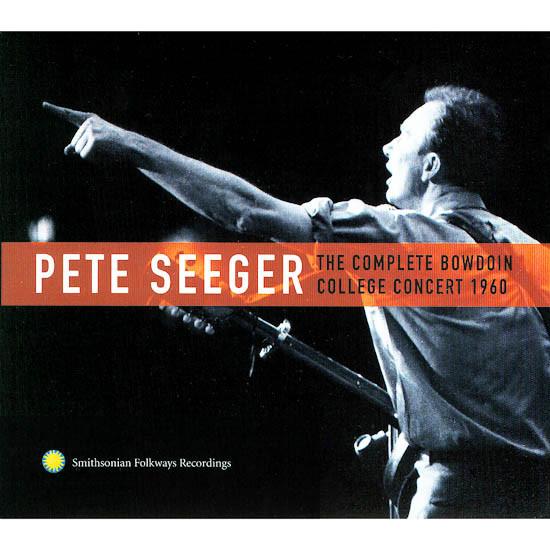

Courtesy of the Bowdoin Bookstore

Courtesy of the Bowdoin BookstoreFifty-two years later, the recording of the concert was released as an album called “Pete Seeger: The Complete Bowdoin College Concert, 1960.”

Seeger was just one of many big-name musicians to visit Bowdoin. His concert was part of Campus Chest, a fundraiser for local charities, which, much like Ivies, was a spring weekend of events intended to raise campus morale after Maine’s harsh winter. The Kingston Trio, Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong, Richie Havens and The Ramones were among the campus visitors in the mid-twentieth century.

Seeger used the concert as an opportunity to teach the audience about folk music.

“That’s right, clear your throats,” Seeger said as he began to strum the chords of “Deep Blue Sea,” seven minutes into the concert. “You’re going to have to sing on this. Some of you know it—those who don’t, now’s a good time to learn.”

His rich, youthful voice adapted to the key changes as he slid his capo up and down the fretboard between songs. And the audience began to adapt to Seeger’s unique concert style, often singing along at his urging.

“When he went out on stage, he was acting as an educator,” said Jeff Place, curator and senior archivist for Smithsonian Folkways Records.

A Visit from an Un-American

Seeger, who died in 2014 but would have turned 100 on May 3 of this year, was famous for bringing folk music to the fore of American consciousness. As a lifelong activist, he wrote, adapted and performed protest songs.

Seeger was a self-described communist and was convicted of contempt of Congress in 1961 after refusing to answer questions regarding his political ideology in front of the House Un-American Activities Committee. As a result of the conviction, he was banned from all television and radio; by 1960, no major record label would sign Seeger. Instead, he recorded his college concerts so they could later be released on compilation albums.

“[Seeger’s concert] was the key event of the weekend. It helped us raise some money. It also helped raise the visibility of the weekend,” said Joel Sherman ’61, the chairman of the Campus Chest Committee in 1960.

That weekend, hundreds of students attended the concert and the Committee was able to raise $533.50 in ticket sales.

Seeger’s Bowdoin concert remained unknown to the world beyond the College until 2012, when tapes of the show were released by Smithsonian Folkways Records.

These tapes owe their existence to Bob McNeill ’61 and Bob White ’63, WBOR’s sound engineers at the time of the concert. They recorded the concert on eight new reel-to-reel tapes. Recordings were typically made by running tape at a rate of 7.5 inches per second (IPS), but McNeill and White recorded Seeger’s concert at a rate of 15 IPS, using twice as much tape but resulting in a remarkably high-fidelity recording.

The microphone captured not only the soft timbre of Seeger’s voice, but also the collision of each metal finger pick on his banjo strings, the crisp tapping of his foot on the stage and the deep united voice of the audience as they sang along.

“It was a requirement that we tape the concert and give the tapes to him,” said Tom Holland ’62, the station manager of WBOR in 1960. “I didn’t realize until later that he could not have a [contract with] big record companies … [this was] the only place where he could make records.”

Holland gave Seeger the tapes after the concert and expected them to end up on compilation albums. Instead, the tapes sat the office of Moses Asch, the owner of Folkways Records, until he died in 1986. The Smithsonian took control of Folkways Records, but the tapes remained undiscovered until 2009.

Jeff Place came across the tapes while going through Asch’s archives. The Bowdoin concert was among roughly 20 taped college concerts from that era.

“Because of the incredible sound quality, it stood out,” said Place. “You can hear him tapping his foot on the stage. It’s really good.”

Communal College Concerts

Seeger’s concerts on college campuses were not only recording opportunities, but community events. He was a folk musician in the truest sense of the term. Though he wrote many songs, the music he was best known for was the music he learned and adapted from others, including members of the crowds at his concerts.

Joe Hickerson was a budding folk musician in the 50s, and was lucky enough to collaborate with Seeger on several songs. The two met at one of Seeger’s earliest college concerts at Oberlin, where Hickerson studied.

“[These concerts were] very important to his career and they were certainly very important to mine,” Hickerson said.

In 1957, after Hickerson had graduated, he returned to Oberlin to attend Seeger’s then-annual concert there.

“At any concert that he gave, there was always a gathering afterwards with lots of singing,” Hickerson said.

It was at this gathering that he taught Seeger “Hieland Laddie,” which Seeger would sing at Bowdoin three years later.

“I learned [this next song] from an Oberlin College student,” Seeger said, introducing “Hieland Laddie” on the Pickard stage in 1960. “I asked him where he got it, he said he got it out of a songbook. But you know, here’s the interesting thing. I looked up the song book and he didn’t sing it like it was in the song book. He’d changed a note here, change a few notes there and frankly he’d improved it. That’s what you call the ‘folk process.’ Glad to say it’s still goin’ on.”

Hickerson remembers the story the same way as Seeger did in 1960.

“I’d never heard anyone sing it,” he said. “I pieced it together the best I could, added some words … So Pete learned it from me—he definitely did.”

Seeger pieced together songs from others and composed new music, following “the folk process.” He took the words to “Turn! Turn! Turn!” from the Book of Ecclesiastes. The words to the hit “Where Have All the Flowers Gone” were inspired by lyrics quoted in a Russian novel and the music was based, in part, on an Irish-American folk song. Hickerson wrote the last two verses (which reference soldiers going to graveyards, and graveyards turning to flowers).

In the years since, Seeger’s songs continue to be sung and improved by the likes of Bruce Springsteen, Bob Dylan and amateur musicians in jam sessions all around the country. “Pete Seeger: The Bowdoin College Concert, 1960” can be found at the Bowdoin Bookstore and on Spotify.

At the end of the album, Seeger candidly concludes the concert: “the only thing that could make me any happier is to know that a lot of you are taking these songs and spreading them around the world wherever you go. That would be the best thing of all.”

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy:

- No hate speech, profanity, disrespectful or threatening comments.

- No personal attacks on reporters.

- Comments must be under 200 words.

- You are strongly encouraged to use a real name or identifier ("Class of '92").

- Any comments made with an email address that does not belong to you will get removed.

I had dinner with Joe Hickerson last night in Portland Oregon. Still going strong, and will be performing this week to honor Seeger’s 100th Bday.