The racial playbook: African Americans and Bowdoin Football

April 5, 2019

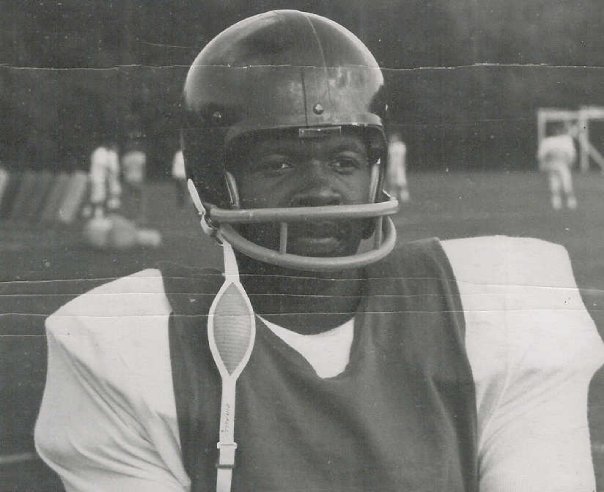

Courtesy of Dr. Maurice Butler

Courtesy of Dr. Maurice ButlerOn a humid August night in 1970, Maurice “Moe” Butler ’74 dropped his trunk at the steps of Smith Union as he headed to dinner. A day early for first-year orientation, Butler could not access his dorm and, with $20 left in his pocket, looked for a patch of floor to spend the night.

One of just 25 African Americans enrolled on campus at the time, Butler left Washington D.C.’s predominantly black inner-city for the whitest state in the Union.

“You have to understand, the College made a decision to go into the inner-city and get some of the best and brightest to integrate the school,” Butler said. “That was a movement before I got there.”

Among Bowdoin’s previous recruits was a talented running back named Al Sessions ’73. Sessions was the inspiration behind a character Butler included in his book, “The Blue Dilemma.”

“His only problem was that he was black, and at that time, blacks weren’t supposed to be intelligent enough to play the quarterback position in college,” wrote Butler.

On the eve of move-in day, Sessions was eating dinner with the football team when Butler walked in. The two became fast friends, and although Butler had never played before, he joined the few black athletes on the team.

“[Bowdoin] wasn’t really the type of school that you had to have a whole lot of experience,” said Butler.

Locked in the gridiron, race may seem like an afterthought as long as the player can “do a job” in the words of former Head Basketball Coach Ray Bicknell. But the playing field’s ability to equate racial differences ignores the social challenges of true integration.

On the field, Butler and teammate Phil Hymes ’77 remember sharing a close bond with teammates on the field, forged through exhausting two-a-day workouts and weekend trips. However, there was a subtle split in the team’s social life. For example, most black students only roomed with black teammates on away trips. When asked about the personal backgrounds of their white teammates, Hymes and Butler offered similar answers. They didn’t know.

“I would say most of them came from New England schools,” Butler recalled. “I don’t know if they were wealthy or not, I didn’t have that type of relationship with most of my teammates to be talking. [There was] a polarization on campus.”

Growing up in an inner-city, Butler did not encounter overt racism until he came to Bowdoin, where the majority of students were white. Some people would exit an elevator when a black man stepped on. Others would yell, “I’m going coon hunting tonight!”

Hymes joined the Bowdoin football team in the fall of Butler’s junior year. After graduating top players the season before, Head Coach James Lentz announced all positions were open, Butler said. Starting positions would be decided purely on talent and commitment to training. In the 1972 season, two top athletes vied to be running back: a white player and Sessions.

“Coach said Sessions was the one for the job,” said Butler. “When he said that everybody said, ‘Whoa, can you believe this guy?’ But when I got into the locker room, I heard ‘nigga, nigga, nigga,’ and I was like where is this coming from? They were angry.”

The night before the season’s first away game Butler roomed with Sessions in the hotel. A recent convert to Islam, Sessions prayed for courage and the strength to perform well for his team. But the next day, every time Sessions touched the ball, he was instantly tackled. In a play known as “Power 1,” it was imperative for Sessions, given the responsibility of tailback, to run with the ball. But the team refused to block for him, Butler remembered. Unable to gain substantial yardage, Coach Lentz removed Sessions from the game.

“Man, he was crushed,” Butler said. “He was almost in tears, and when we got back to the school, he quit.”

Against the backdrop of the Civil Rights Movement, this was a highly unusual event to happen at Bowdoin. In fact, it was the worst and, thankfully only, racist display Butler encountered on the football team.

“But it was ugly,” Butler said.

Butler recalled that, in a move of solidarity, the majority of African Americans left the team with Sessions. Butler stayed. He began to notice a small crowd of black students gathering at Whittier Field on Saturdays, only to leave when Butler couldn’t play after an injury. No longer playing for himself or his team, Butler worked hard to entertain his loyal fans.

Football took on a new shape in Butler’s life. It became a much darker and physical game than before. Each hit was an opportunity to not only execute a play, but harm the man on the other end.

“I was angry with white people,” Butler said. “I was raised to judge people by the content of their character, not what they look like. But you know, at that time, I was just enraged.”

In the mid-1970s, the College began to confront underlying racial tensions. Butler, and other prominent athletes such as Geoffrey Canada and Stephen Morrell, established a commission to investigate the athletic department. Yet when Hymes graduated in 1977, there were no marked improvements in place.

More than wanting close relationships to their teammates, African American students wanted a place to call their own at Bowdoin. Established in 1969, the African American Society served this purpose, but among white students, its message was lost.

“Some of our classmates did not have that understanding of why it was important to us,” said Hymes. “That was always the question.”

The African American Society celebrates its 50th anniversary in November this year. Outspoken proponents in Bowdoin’s mission to create an inclusive society, such as Butler, will return to campus for the celebration. And while it is important to recognize the achievements of the current administration, it is even more helpful to remember a time before race and sexuality were common topics at Orientation. One racist act does not define a campus, but the collective response and future work toward prevention, can define an entire movement.

“Lots of things you have to learn through experience,” Butler said. “It was one incident. I dealt with it, but that was not my total experience on the football team, and I love and enjoy playing football.”

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy: