Oil, gas and other precious commodities

April 5, 2019

Phoebe Zipper

Phoebe ZipperWe talk a lot about hometowns, both in our casual conversations and within the pages of the Orient. Given that this is a column on our home state of Texas, we felt it’d only be fitting to pay our respects to our home cities in the Lone Star State—places that, by virtue of their complexity and size, dazzle and confound us, often at the same time. What follows is part-rumination, part-conversation on what we’ve learned about our homes since being removed from them for the past four years. This is Houston.

Phoebe: There’s a dark grey cloud blotting out the sun. I’m home again for break, and my mom and I sit in the Houston traffic, trying to puzzle out what’s going on with the sky. A tropical storm maybe? But hurricane season doesn’t start for months. The cloud’s borders are unnaturally blunt and precise, graphic like a pop art cartoon. It’s less of a fog and more of a charcoal smudge against the sky, trailing down to the ground in a neat plume. The cloud, our local news anchor tells us, is actually smoke, the result of a fire at the Deer Park petrochemical plant in east Houston. Ten days later, a sickly pink, dead dolphin washes ashore in Galveston, a neighboring city on the gulf coast. Whether or not there was a connection remains unclear.

For many of us at Bowdoin from the American South, it can feel like we’re here partly because we cultivated a mild disgust for where we come from. A resentment towards Texas and the oppressively conservative culture of my private high school were certainly large reasons behind why I looked almost exclusively in the northeast during my college search. People gathered in dimly lit rooms around wooden tables discussing, you know, great works of literature.

Surya: @PeucinianSociety?

Phoebe: Something like that. Knowledge like a petrochemical haze in the air, students picking apart history to get at kernels of reality and truth. That was the fantasy.

Surya: This rings so true to me and reminds me of the nagging feeling that comes over me so often when talking politics with Bowdoin friends (i.e. I left Texas thinking that outspoken Texas conservatives were the devil, but have found, in time, New England liberals to be just as insidious in some ways).

Phoebe: Right? Up until recently (thanks, Beto), if you were a liberal in Texas, you really had to get behind your politics in a way that isn’t required of you in New England. Or just shove them down and never talk about it. It’s probably a cliché at this point, but four years and many miles of distance between me and Houston have allowed me to recognize the ways in which my hometown holds truths equally as important and complex as the ones studied in the classroom.

Houston is a place that often confronts you with ugliness and without illusion. The city sprawls out endlessly in all directions, the flat landscape blanketed by a constellation of mega-highways that make a modern, nightmarish mockery of the phrase “everything is bigger in Texas.” There’s no escaping the energy industry, from the petrochemical refineries that mushroom along the ship channel in east Houston to the businessmen that commute downtown every day to bundle, buy and sell the natural gas that powers our lives, my dad among them. There’s equally no escape from the heat—relentless, nearly suffocating in its humidity.

Surya: As an Austinite who only visited Houston for weekend soccer tournaments, I’d also like to add that Houston’s humid climate boasts some of the most bountiful greenery west of Louisiana. My memories of Houston are shrouded in soft green grass and storybook mega-mansions. The money made the place all the more unreal to me.

Phoebe: Yeah, it’s this strange juxtaposition of the lush and nearly tropical alongside Texas as the edge of the southwest and also alongside the southern charm. There’s definitely a media narrative out there these days that loves to lift Houston up as an incredibly multicultural society, but I think what makes the city so interesting is the ways in which these often struggling immigrant communities exist alongside a parallel culture of vast, ostentatious oil wealth. It certainly made for an interesting mix in my high school.

So, like all great cities, Houston is a place of contradictions. The oil and gas industry generated the money that made the city a great center of philanthropy and public art: we would not have the Rothko chapel if it wasn’t for Schlumberger.

Surya: Again, Austinite and art novice here: what’s a Schlumberger?

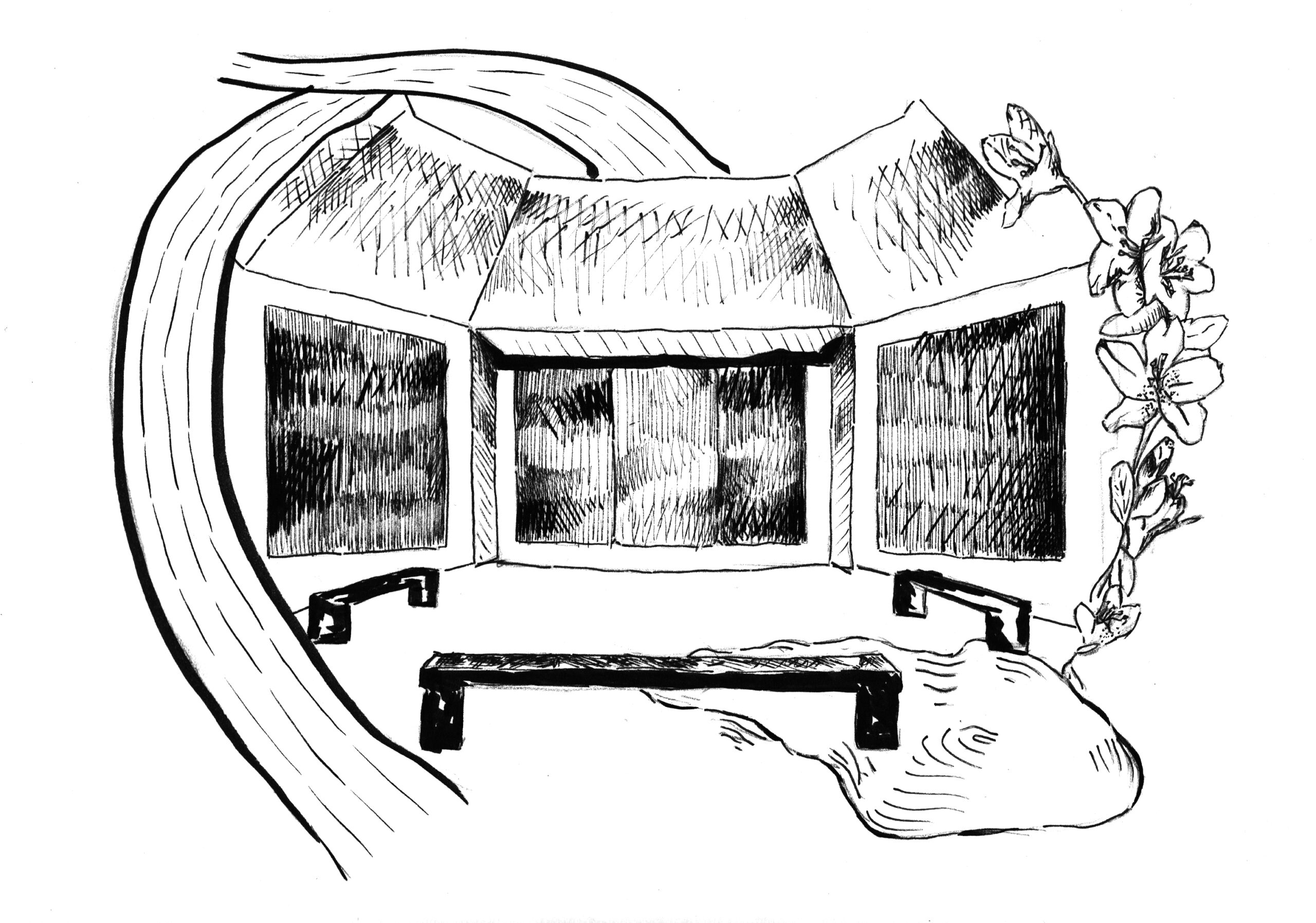

Phoebe: It’s an iconic oilfield services company. The heiress to the money from that company, Dominique de Menil, went on to found this amazing, tranquil oasis of an art museum. The Menil campus is lush Houston greenery at its finest. But anyway, the money from the energy industry is the money that’s bubbling under the melting pot of diversity that the city has become, money intertwined with a sprawling story of immigration, economic development and the birth of a sort of uniquely Texan cosmopolitanism. I’m not really tribal or emotional about my hometown, the way I think it’s easy to be in this age where we’re all globally connected but also constantly displaced and shuffled away from our roots—in search of the next job, degree, line on the resume.

Surya: And why would you feel tribal about Texas? Our families are both transplants.

Phoebe: Right, like who even knows where I’m supposed to locate my roots at this point? But I am deeply appreciative of Houston. I love the way perfumed 20-somethings wear cowboy boots to brunch even though we live in a swampy urban jungle, the way that we’re always the underdog, the fact that the things that make Houston great also make it difficult.

There is no escaping the fossil fuel industry, it’s true, or the overt bigotry that still permeates many corners of Texas. But in Houston, it is also impossible to run from the realities of American life—where it has been, where it is going. It’s there in the post-Civil War freedmen’s cottages in the Fourth Ward, in the immigrants that continue to arrive not just from Latin America, but from India and Nigeria and Vietnam, in the Hurricane Harvey wreckage piled in the bayou like an omen of climate change to come. But where there’s ugliness, there are always ways in which it is intertwined with beauty. In early March, the Houston air starts to grow heavy with humidity again, and azalea blooms gush forth against that dark, prickly Texas grass: red, magenta and white brushed with the barest hints of pink.

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy: