How does Bowdoin get its money?

Endowment returns and tuition fund normal operations, donations drive construction

April 5, 2019

In recent months there has been a pattern of stories in the Orient exploring the complexities and limitations of Bowdoin’s endowment and operating budget. To add context to the series of articles and op-eds, the Orient has decided to break down the numbers behind the money that makes Bowdoin run.

This is Part 1 in a two-part series examining Bowdoin’s budget. This week, we look at the College’s sources of revenue. The second installment, published next week, will examine its spending.

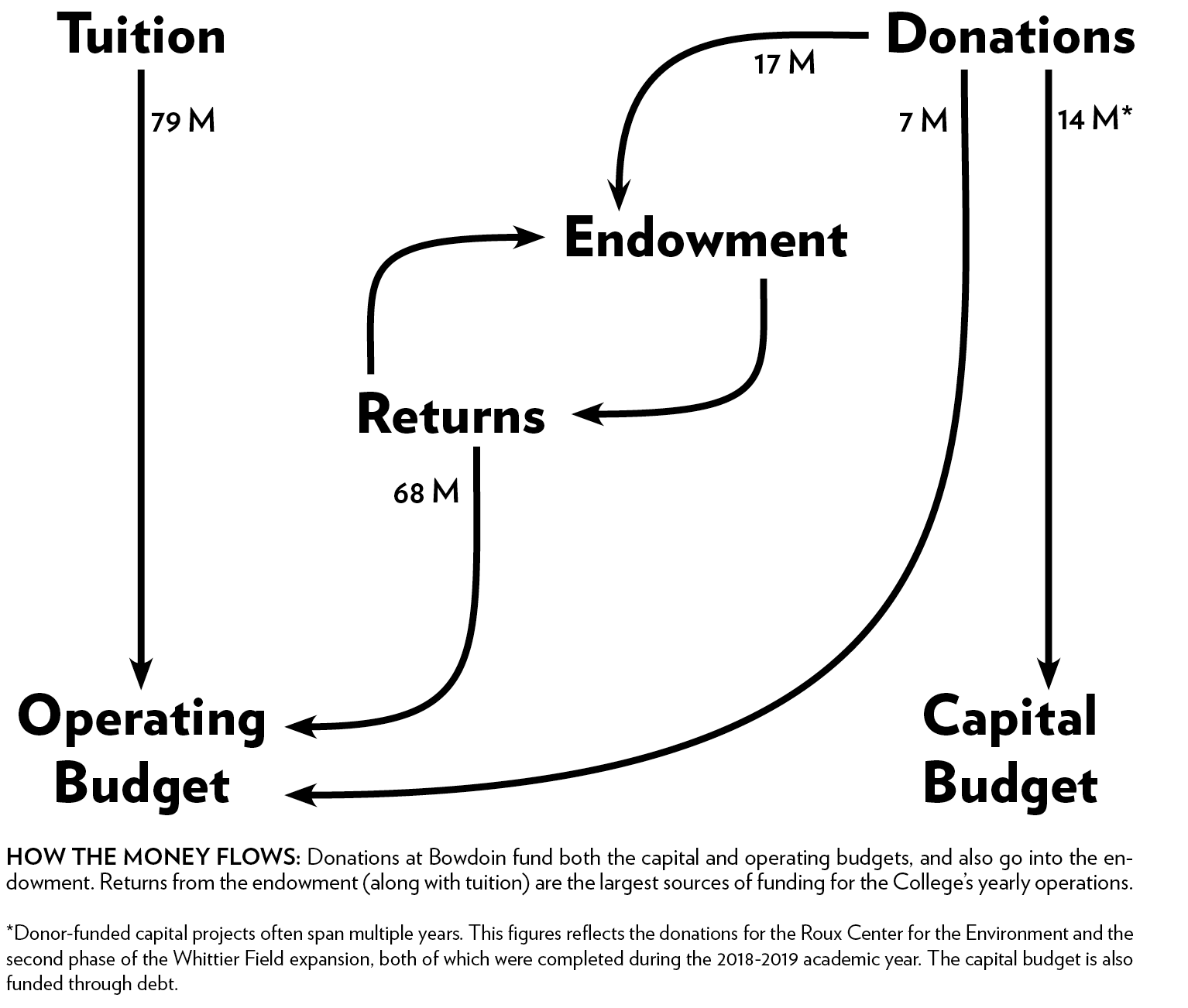

Bowdoin draws its revenue from three main sources: tuition, returns on the endowment and donations. The money that the College spends each year is generally split into the operating budget and the capital budget. Understanding the finances of an institution as large and multidimensional as Bowdoin is complicated, but breaking down the data from the Office of the Treasurer makes it a little easier.

Operating Budget vs. Capital Budget

Each year, the Office of the Treasurer prepares two distinct budgets: the operating budget, which is the annual cost of running the College, and the capital budget, which is spent on construction projects and renovations.

The operating budget pays for everything from financial aid for students, to the food in the dining halls, to faculty and staff salaries.

This academic year, the funds available for the operating budget are $168.4 million, up 3.4 percent from last year’s budget when accounting for inflation. On the spending side, the College is spending more on student wages and financial aid.

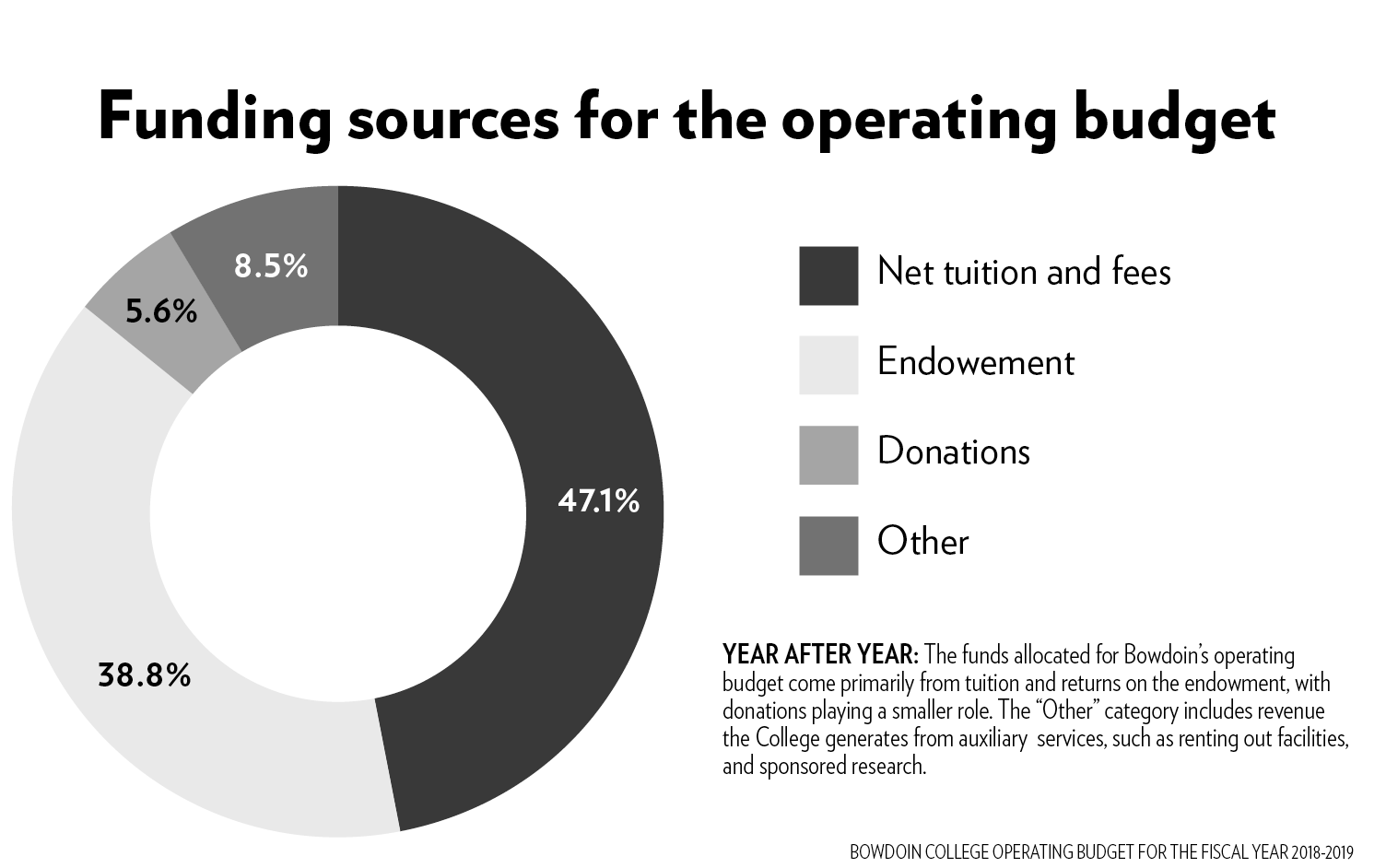

Net tuition and fees (the total amount of tuition due to Bowdoin minus the amount of financial aid distributed) cover 47.1 percent of the current operating budget. Funds from the endowment pay for 38.8 percent. Unrestricted gifts, which are donations that the College can use to its discretion, cover 5.6 percent. The remaining 8.5 percent comes from other sources, such as revenue from renting out facilities and sponsored research.

The capital budget, meanwhile, pays for larger projects and maintenance in excess of $500,000, including construction projects such as the Roux Center for the Environment and Park Row Apartments.

The College is currently in the midst of a $153 million capital plan, which spans six years: fiscal year (FY) 2017 to FY 2022. Of that, Treasurer Matt Orlando anticipates spending $35-40 million this fiscal year on projects such as the construction of Park Row Apartments and the renovation of Boody-Johnson House.

The capital budget varies year to year and is unusually high this fiscal year, which Orlando attributes to the several ongoing construction projects. From FYs 2012 to 2016, capital budget spending ranged from $5-10 million per year.

For the most part, capital projects are financed through donation, debt or a combination of the two. Financing through debt means that the College issues bonds which are purchased by banks, or—more commonly—purchased on the public market. Proceeds from bond sales contribute to the capital budget. The bonds with interest may be paid off either incrementally or all at once, and the payoff term is typically 30 years.

The College prefers to finance capital projects through debt because the interest rate the College has to pay back on bonds tends to be lower than the rate of return on the endowment, which means the College is getting more money from the endowment every year than it is paying in interest on the money it borrowed. Most recently, the renovations of Boody-Johnson House and the construction of Park Row Apartments were financed through debt.

Capital projects can also be financed through donations. The Roux Center for the Environment, for example, was paid for by a donations totaling to $12.5 million from David and Barbara Roux and other donors.

COURTESY OF GEORGE J. MITCHELL SPECIAL COLLECTIONS

COURTESY OF GEORGE J. MITCHELL SPECIAL COLLECTIONSEndowment

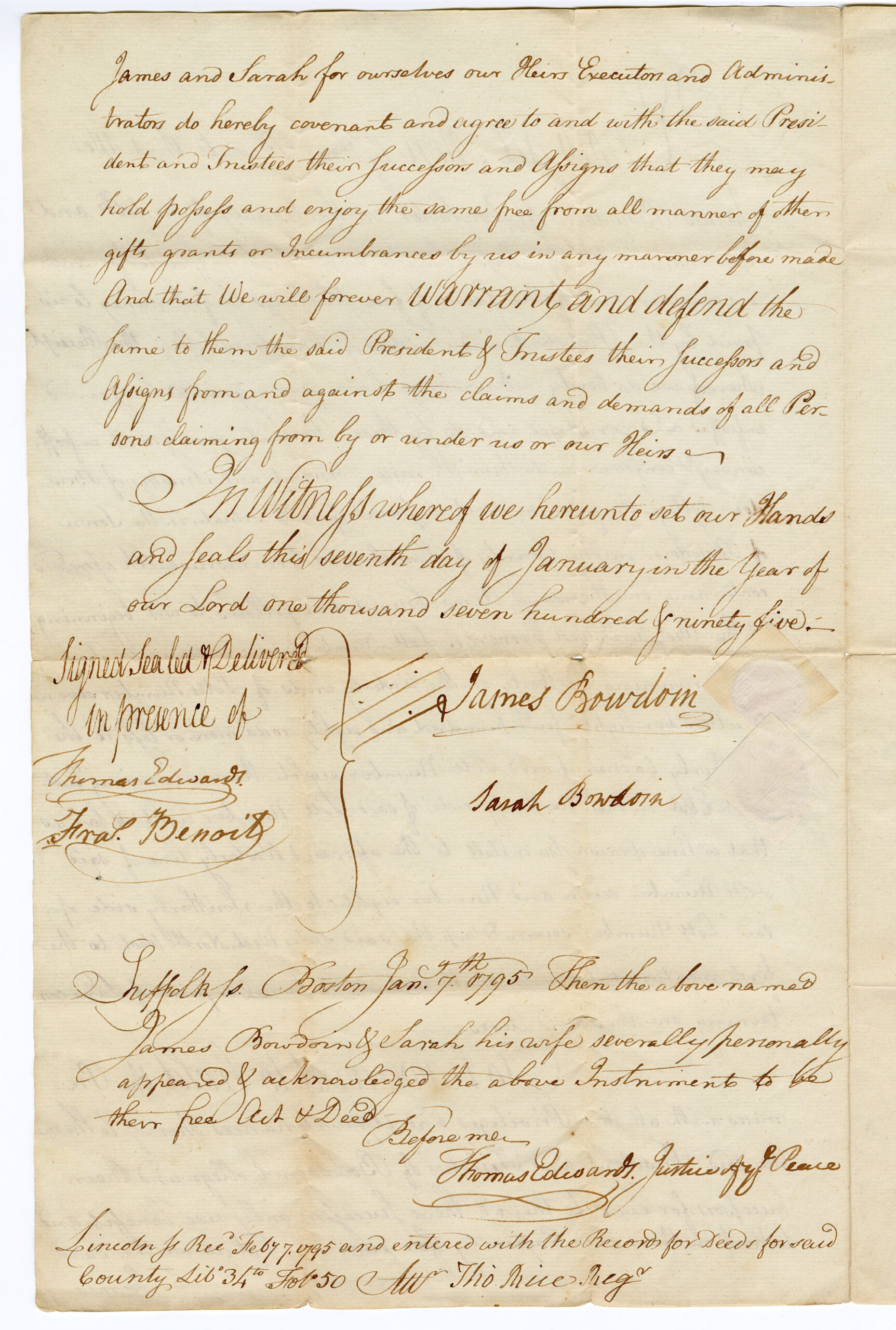

Bowdoin’s endowment is as old as the College itself. Shortly after Bowdoin received its charter in 1794, James Bowdoin III gifted the college $1,000 and 1,000 acres of land and later endowed a professorship in mathematics or natural and experimental philosophy. In 1802, his wife, Sarah Bowdoin, endowed a professorship in modern languages.

Several centuries later, the endowment has become crucial to Bowdoin’s finances. For this academic year, returns from the endowment made up roughly 38.8 percent of the funds available for the operating budget.

Bowdoin has had particularly strong endowment growth over the last decade. It made headlines last fall as one of the best performers among any college or university in the United States, with a 15.7 percent rate of return. As of June 30, 2018, the endowment was valued at $1.63 billion.

Strong endowment growth is good, but it doesn’t mean that the College has $1.63 billion at its disposal. Endowments are designed to pay out interest, often around five percent, each year. If the endowment grows at a rate higher than the payout, it will be positioned to continue generating income for the College year after year, for an unlimited amount of time. The recent strong returns have allowed both the endowment and the operating budget to grow significantly in recent years.

Bowdoin draws out between four and 5.5 percent of the endowment’s 12-quarter moving average to fund a year of expenditures. The 12-quarter moving average means that the College chooses an amount based on the average value of the endowment over the previous three years, rather than its current value. This is designed to prevent significant market swings from affecting the payout.

The exact percentage that Bowdoin withdraws each year is recommended by the College’s administration, reviewed by a committee within the Board of Trustees and then voted on by the full Board during its May meeting.

For the FY 2018-2019, Bowdoin withdrew $67.7 million from the endowment. For the coming fiscal year, the College expects to withdraw roughly $71.8 million.

Endowment growth can happen two ways. Endowment returns, which amounted to more than $200 million last year, are the primary driver of growth, but the endowment is supplemented by donations. During the FY 2017-2018, the endowment received $16.5 million in donations. These donations become part of the core of the endowment that will generate returns in the future.

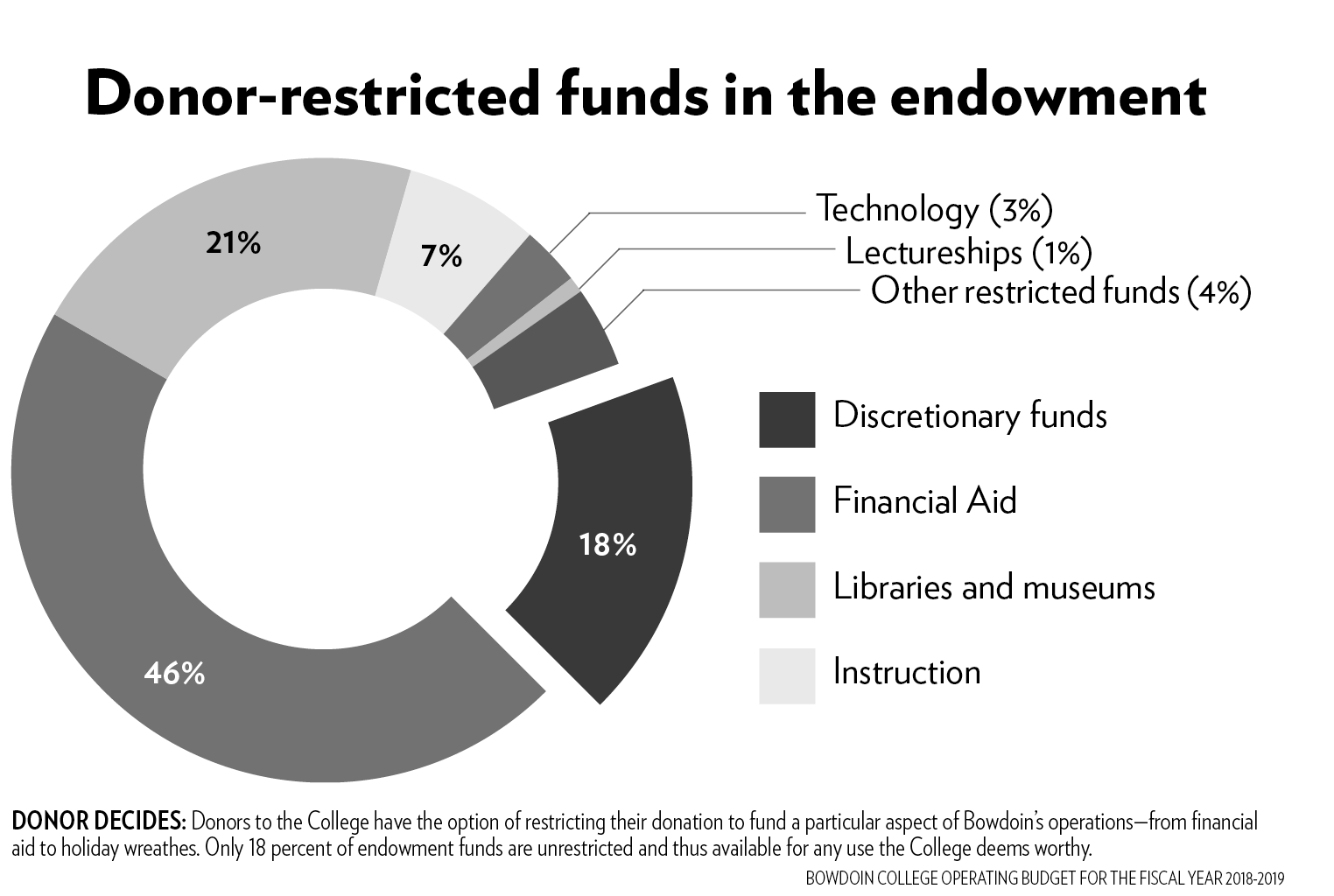

However, most of the endowment is donor-restricted, meaning that the College is legally required to use it toward a certain cause specified by a donor. For instance, returns earned from Sarah Bowdoin’s donation can only be used to fund a professorship in modern languages.

Roughly 46 percent of the endowment is restricted for financial aid; 21 percent is for instruction; seven percent for libraries and museums; three percent for technology; one percent for lectureships and four percent for other programs, including the McKeen Center and the Outing Club. Thus, only 18 percent of the endowment is available to fund the College’s other expenditures.

Going forward, Bowdoin’s endowment will run into one additional challenge: the endowment tax. Passed in December 2017, the policy imposes a 1.4 percent excise tax on colleges and universities with endowments greater than $500,000 per full-time student (Bowdoin’s endowment sits at nearly $900,000 per student). The tax will take effect for the first time for the 2018-2019 FY returns, although, in the absence of federal guidance, the College is still determining exactly how its finances will be affected.

Tuition

Tuition dollars make up 47.1 percent of Bowdoin’s budget. This figure reflects net tuition—the hypothetical total amount of money the College would receive if all students paid full tuition minus the amount of financial aid administered, or a simple sum of all students’ tuition payments.

Though tuition dollars play a significant role in funding the students’ day-to-day experiences, tuition doesn’t cover the whole cost of the Bowdoin experience. The operating budget divided by the number of students provides a glimpse into how much it actually costs to educate a Bowdoin student: $92,315 per year.

How is this money spent? Check back next week.

Editor’s note, 4/5/19 at 12:07 p.m.: A previous version of this article incorrectly described the sources of donations for the Roux Center for the Environment. The phrasing has been amended.

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy: