Myth-bound borders and the mama bear of west Texas

March 1, 2019

The bear wasn’t supposed to be there. It was just a black one, a mother whose deep eyes held ours for too long—so long that we continued to lock eyes, paralyzed, our weary knees locked by both reverence and fright. Black bears were supposed to be shy; they were supposed to wander in pockets of wilderness where humans and their cars were sparse. But the bear was there nonetheless, only a few feet off the trail, a mother with a small cub sitting by her hind leg.

We had been stumbling our way towards the end of the trail, the low-slung motel roof and crowded parking lot of the Chisos Mountain Lodge finally starting to materialize through the trees. Our 10-mile hike to the precipice of Emory Peak was nearly over and done: we had made it up, and then down, from the highest point in the Chisos Mountain Range, the rigid spine of mountains that bisects Big Bend National Park.

Phoebe Zipper

Phoebe ZipperThis stretch of Texas, the far west that sits nestled between the Rio Grande and New Mexico, had always loomed large in our imaginations, and we had set aside a week over Winter Break to explore it together. It was a place that was looming larger in the national debate as well. The Mexican border, and all of the political noise that surrounded it, seemed to hover around the edges of each conversation and just beyond the horizon of every empty vista.

Our sojourn to Brewster County began in El Paso, where we took Beto O’Rourke’s hometown as a good luck charm and ran, racing through abundant orange-capped mesas and U.S.–Mexico border checkpoints. We searched through miles of highway for all of the myths we had projected onto this landscape. These were visions of a vast, untamed wilderness, of American lawlessness and echoes of a land before time. There were images of a national park frozen amidst a government shutdown, of migrants stranded in no-man’s land, of super-sized burritos and of a pulse that might be the heart of the place, the heart of Texas perhaps, in the way that the whole nation seemed to flow south and peter out here.

What we found was a lot of openness, a lot of nothingness, a lot of silence and a lot of air.

Like the mother bear, or a Prada store in the middle of the desert, the landscape of West Texas felt both real and unreal, unbounded and elusive. We spent our first night in the tiny community of Marfa, which rose to art-world prominence after contemporary sculptor Donald Judd decamped there from Brooklyn in the 1970s. The main street of Marfa yawned unnaturally wide and held that kind of expansive, eerie silence that only lonely small towns can claim. Except around the corner, there was a peel of female laughter—a group of women arriving from Austin, clad in cowboy boots and leather fringe, posing for a photograph. We saw them again later that same day in a coffee shop, where they sipped turmeric lattes. A table over sat another couple in black, silently flipping through “The Gentlewoman.” New Yorkers, definitely, Surya quipped.

But Marfa still eluded us. There was a bubbling under the surface of the town: the galleries that seemed closed but were really open, the waiter who said he was leaving for his smoke break only to disappear, the security guards who strolled around Donald Judd’s “100 untitled works in mill aluminum” in jeans and black hoodies. There, at Judd’s Chinati Foundation, it was unclear where our personal agency stopped and authority began.

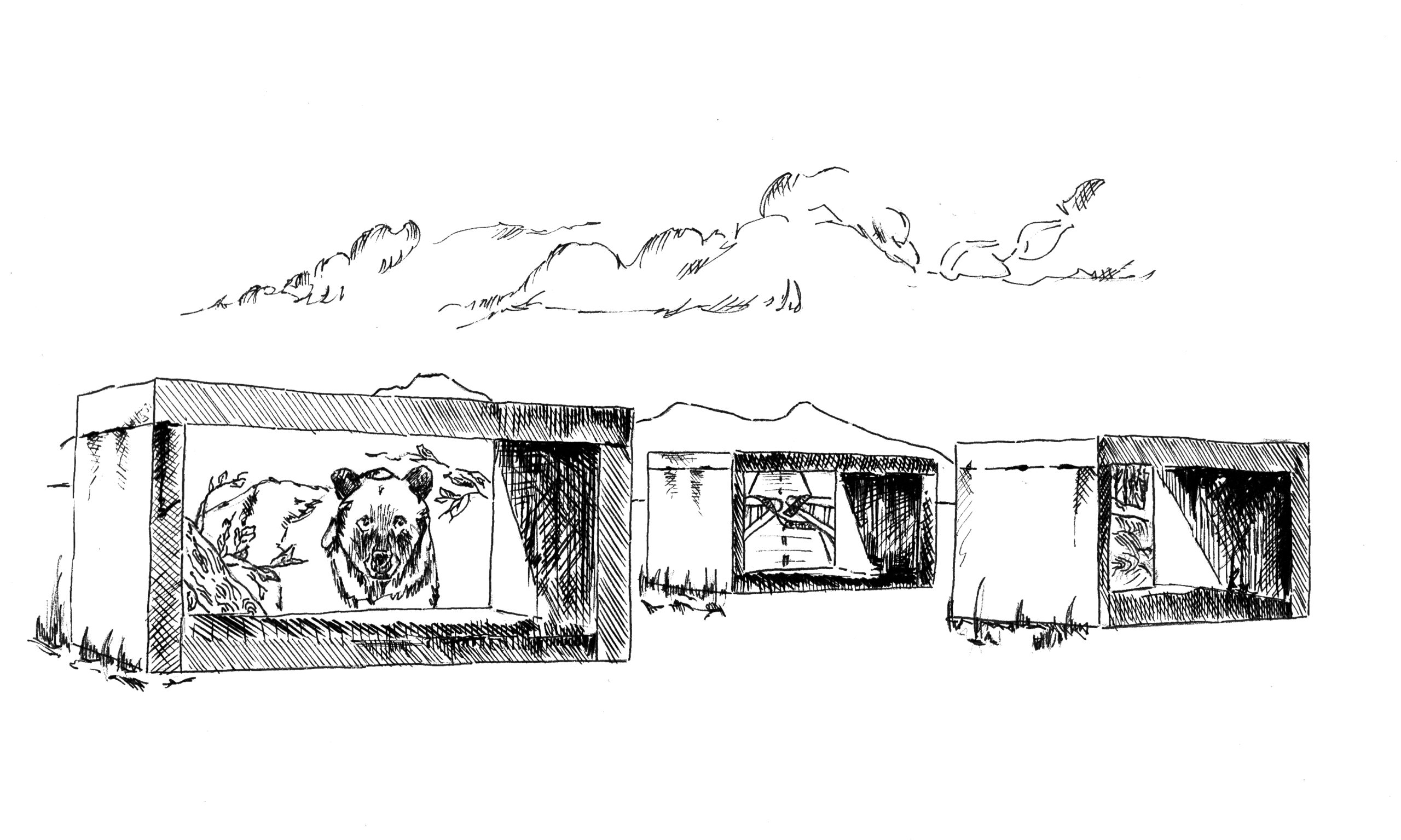

Outside, we drifted through his “15 Untitled works in Concrete”—these huge, hollow cinder blocks that framed the merging of desert and sky. They were industrial, achingly minimalist, but they belonged. The border between the man-made and the natural, it turns out, is also arbitrary.

These contradictions did not ebb—even after we quit Marfa, looking to shake the feeling of toeing the town’s boundary lines: between silence and community, cowboy kitsch and art elites. But Big Bend, like Marfa, felt both of and not of its place.

Our first night in the wilderness, we trekked to Boquillas Hot Springs, a stone-studded alcove on the north bank of the Rio Grande. Elbows propped on the edge of the warm lagoon, we pointed across the stream at a towering mess of brush: to Mexico, that place where you need passports and plans and maybe some broken high-school Spanish. It felt too tangible, nothing more and nothing less than the other bank of the river. The federal government was a prickle on the back of our necks, just a tension in the air. Phoebe fought the urge to swim across. When we left, we did so only because the night had made itself welcome.

Handcrafted tchotchkes of vibrant colors, made by Mexican artisans and left out for purchase on the honor system, sat near the hot spring’s dusty car park. As with the limestone cliff drawings all around us, or the standalone Prada installation back in Marfa, the people behind the art were nowhere to be found. So when we endeavored to witness the 1,500-foot-tall Santa Elena Canyon—keen to see its towering limestone cliffs and leafy depths—we didn’t really heed the park’s warnings that the area was closed to the public. We drove in anyway. Halfway down a should-be-shuttered road, we arrived at the plastic white blockade that heralded the boundary of our own journey. The powers that be were there, we felt, and we heard their gentle whisper: turn around.

So we did turn around eventually, winding back through Marfa, then Alpine, and finally Midland, the energy hub at the heart of the oil-rich Permian Basin. Separately we flew into Portland, traveled up Route 1 by car, trudged across Maine Street to campus. Feet firmly planted in the Bowdoin bubble, the government shutdown continued and the border was back in the news. Things on the screen seemed so clear, conversations with friends charged with moral righteousness and easy solutions. The insularity of Bowdoin, we felt, was so good at making us feel like we could reduce the nation’s largest problems into smooth narratives: of displacement and delusion, on the part of our government and those on whom it exerts its control.

But the reality was, the closer we were to the border, the less clear things seemed. Our movement through west Texas was a constant negotiation: between ourselves and the desolate Chihuahuan desert, our low-slung Nissan Sentra and the pointed inquiries of border patrol agents, our own survival instincts and the black bear’s maternal ones. At Bowdoin, the powers of nature and of state often feel distant and diffuse. But in the vastness of west Texas, they felt visible and then primal—at once there and then quickly out of our grasp.

Caught in the bear’s gaze, we were also caught in a quiet tug-of-war over who held power in that moment. In the end, it was her home, not ours. We raised our arms and made a run for it.

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy: