Facilities workers struggle to make ends meet

Employees in grounds- and housekeeping sometimes receive below living wages. The College knows they struggle.

May 4, 2018

Ann Basu

Ann BasuBeginning at 5 a.m. on the Sunday after students finish their exams, Bowdoin’s housekeeping staff will work for 10 straight days, many of them for 10 hours, readying the school for graduation and reunion in the following weeks. The workers will clean 25 dorm buildings in 10 days. It’s an annual ritual, and a grueling one for some housekeepers.

Each year, it’s a push to get it done. “It’s mentally and physically stressful,” said one housekeeper, who asked to remain anonymous. But it’s vital to making the school look presentable and impressive to the important guests who will soon arrive.

It’s also a time when employees clock overtime wages and hopefully put some money aside.

For many facilities and housekeeping employees, the extra savings are crucial. An Orient survey and interviews with 18 housekeepers and groundskeepers reveal that many of these workers live paycheck to paycheck. Their stories illuminate a workforce in which some employees lead lives of poverty and financial insecurity at a College that makes the common good a core element of its mission.

Interviewees reported financial insecurity in various ways. Some have difficulty paying normal bills and putting food on the table, while others say they have just enough to cover that week’s expenses but are unable to put money aside to save for the future, or in case of emergency.

“If the kids in the locker rooms leave food behind, that’s our lunch. If they’re not going to eat it, I’ll eat it,” said Beth Icangelo, a housekeeper who cleans Watson Arena among other duties.

“For what I make, I can just barely pay bills. I never have money in my savings account. Never. Literally right now, I have $2.50 in my bank account. It’s definitely a struggle,” said Gabriel Grindle, a groundskeeper who has worked at Bowdoin for almost 15 years. “I also have a kid at home. That definitely doesn’t help financially.”

“We used to have to go to the food bank—more often than I care to have to admit because we just would have enough to pay rent or pay whatever because I had kids at home,” said a housekeeper who asked to remain anonymous.

“I have a car that needs an inspection sticker, but it’s going to cost $1,000 to get it inspected, and it was due last October. I’m driving around with a vehicle that’s not inspected but I don’t have the money,” said a groundskeeper who asked to remain anonymous.

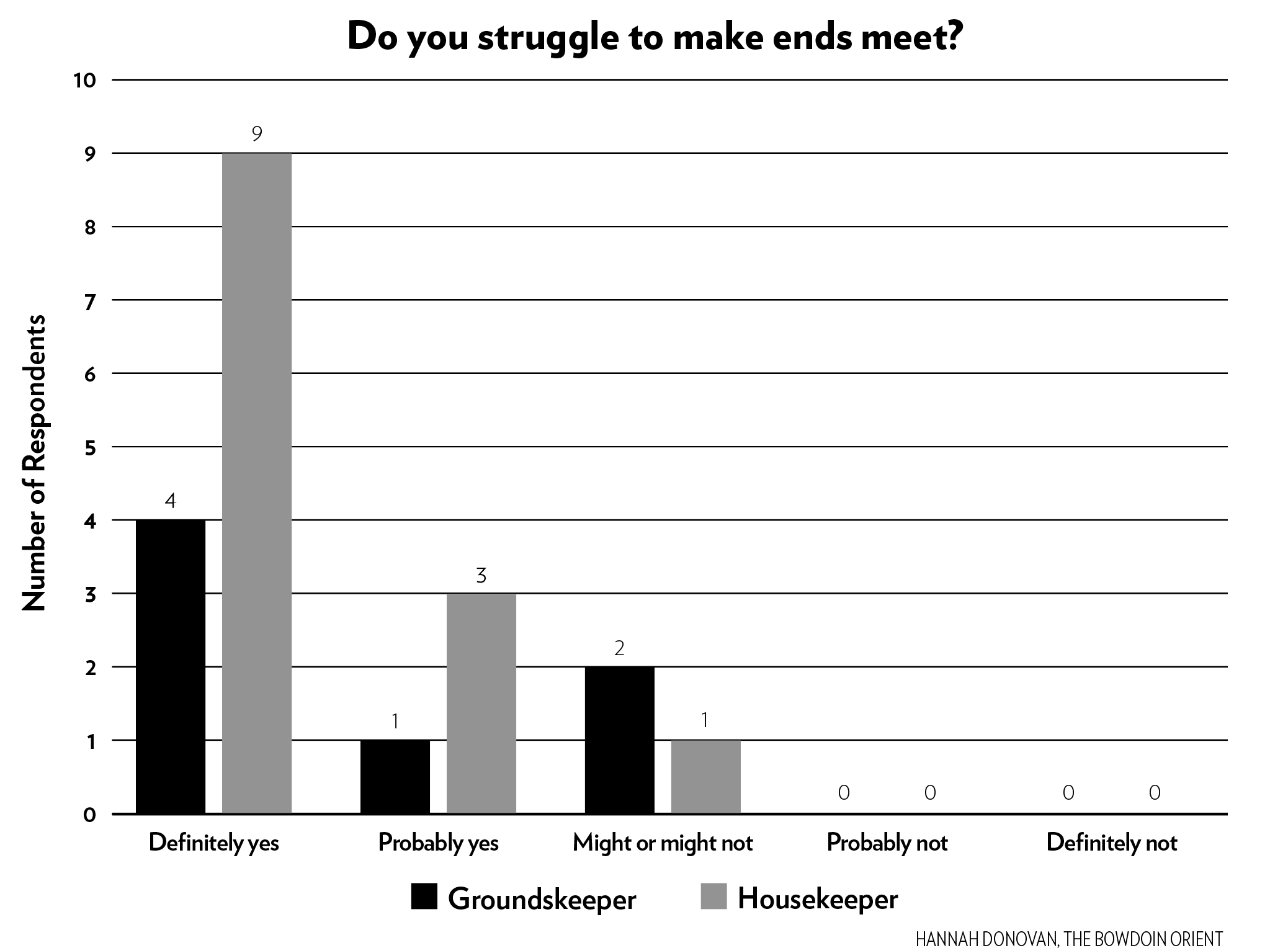

Last week, the Orient sent a survey to 112 facilities employees and received 29 responses. Twenty-two respondents said that they struggle to make ends meet.

Twelve survey respondents said that they work another job to supplement their Bowdoin income. Six said they do so sometimes.

Karen Doyle usually works at least 40 hours a week as a housekeeper at Bowdoin. On some days she leaves work at the end of her daily shift at 1:30 p.m. and drives to a house she cleans for a private client. For her, this is physically exhausting and leaves her with little time to see her partner, a meat cutting associate at Hannaford. He left his job in Bowdoin housekeeping a few years ago because the pay at Hannaford was better, and he found the benefits to be comparable. When Doyle’s children lived at home, just a few years ago, her work meant she frequently wasn’t able to see or care for them.

For many in housekeeping and groundskeeping, the ability to meet expenses depends on whether they have another income-earning individual in the household or have to provide for dependent children. Interviewees with children were more likely to say that they struggled financially. Some reported their situations changing once their children moved out. Many interviewees who have a working spouse said that they only make ends meet due to the higher wages of their partner.

One housekeeper, who requested anonymity because she did not want to be identified by co-workers or management, said that she was in the beginning stages of a divorce and expressed concern about financial stability once she is unable to rely on the wages of her spouse.

“How in the world am I going to be able to live on $12.50 an hour?” she said. “Obviously he can help, but it’s not the same as having two full incomes. It’s a scary thing to stop and think, ‘How do you live on—pay a vehicle payment, insurance, rent?’”

Sabrina Bouchard, a housekeeper who has worked at Bowdoin for 11 years, said she used to work multiple jobs when her children lived at home. Now that they have moved out and she has fully paid her mortgage, she says she is able to comfortably support herself on her Bowdoin salary.

“I don’t have to do those [extra] cleaning jobs anymore. I wasn’t doing it because I wanted to. I was doing it because it was necessary,” she said.

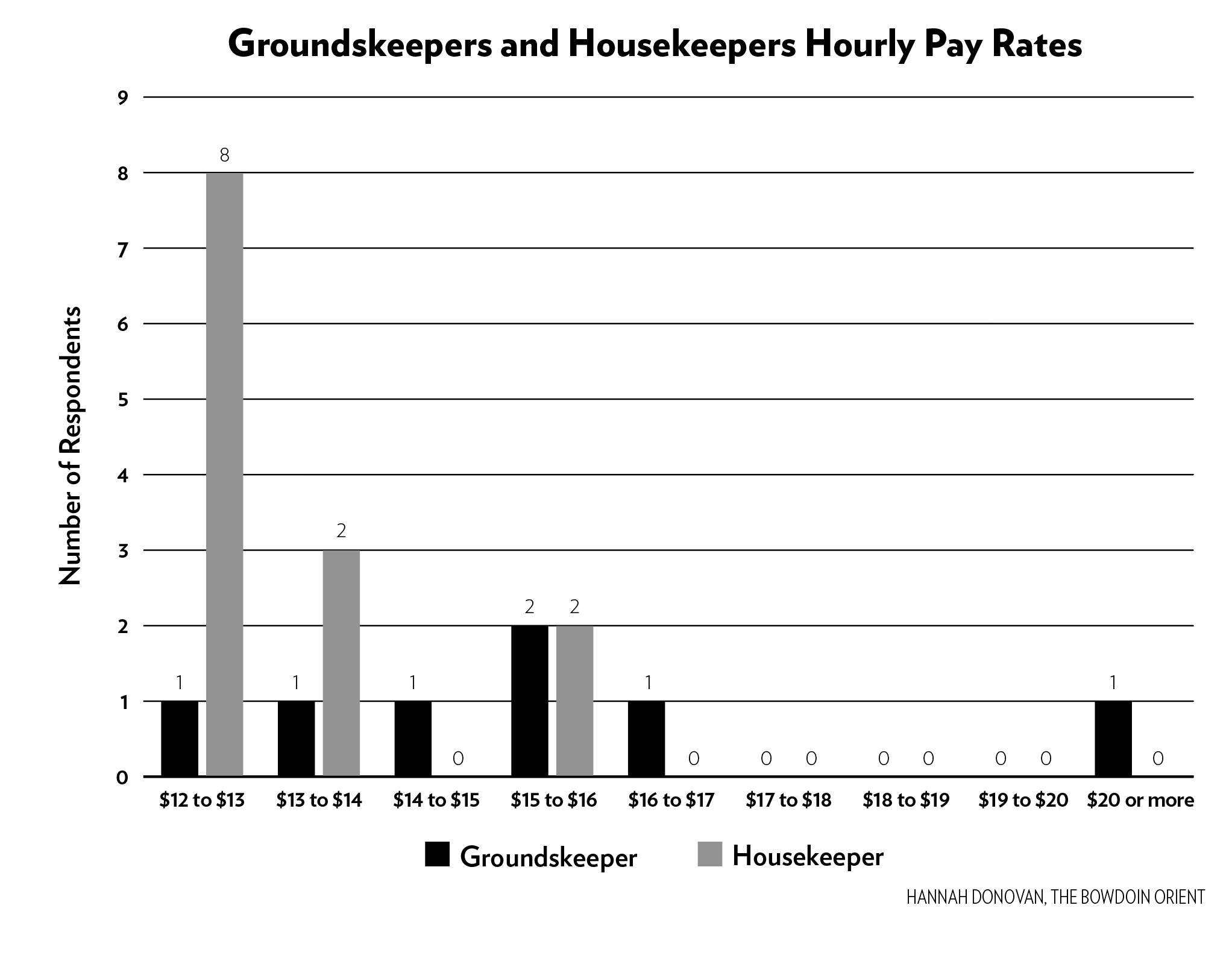

The 29 individuals who reported their current hourly wages on the Orient’s survey had earnings ranging from $12.03 per hour to $30.79 per hour. The mean wage reported was $16.54 per hour. Fourteen employees, nearly half, report making below $15 per hour.

Within housekeeping and groundskeeping, the ranges and averages were lower than in the total sample. In housekeeping, no worker made over $15.42 per hour and eight reported making less than $13 per hour. The average wage was $13.09. Within groundskeeping, the highest income reported was $22.42, while the six other respondents reported making under $16.83 per hour.

Band-aid solutions

Earlier this spring, Tama Spoerri, vice president of Human Resources (HR), put the cost of a Central Maine Power reconnection bill for a Dining Service employee on her Bowdoin credit card. The money came out of either the Paller Fund or the Bowdoin Staff Assistance Fund, endowments which are specifically designed to cover expenses for employees in times of hardship. In this case, the Dining employee had reached financial dead end, Spoerri said. She had had a large medical bill, her car broke down and she received a disconnect notice after she wasn’t able to pay her power bill.

After six months of work at the College, each employee is able to request support from these funds, provided they document need. Multiple workers interviewed mentioned using the funds at some point during their time at Bowdoin. For some, the emergency assistance was a crucial lifeline pulling them back from the brink of financial freefall, and they were grateful that the College could support them.

At the same time, the existence of these funds reflects the College’s awareness of its employees’ financial insecurity, and that it has adopted a system of charity rather than a living wage to deal with the problem.

“We get it—how hard it is to live paycheck to paycheck and to not know—a broken down car will be the next financial disaster. We are mindful of that,” said Spoerri.

Spoerri mentioned that she had referred employees to other forms of charity, such as the United Way 211 service, an online directory of resources available to people in need, filtered by location. United Way offers links to local food banks, resources for enrolling in supplemental income or food assistance programs and finding emergency shelters, among other services.

A little better than Walmart

In an interview with the Orient, Spoerri and Senior Vice President for Finance and Administration and Treasurer Matt Orlando indicated that the College sets wages based on a calculation of what employers nearby are paying. While Bowdoin’s hourly wage is comparable to that of similar employers, the College hopes to attract workers with a significant benefits package.

“We look at, what does McDonald’s hire? What does Amato’s hire at? What is Walmart hiring at? Et cetera,” said Spoerri. “The fact is that many of those employees don’t have any benefits. We offer paid time off, sick time, vacation time, disability.”

In making such a comparison its practice, Bowdoin has tied wages and benefits for its workers to employers like Walmart, which has made headlines for having record numbers of workers who use SNAP benefits and is notorious for paying non-livable wages. Many studies have documented Walmart’s ability to substantially influence wages in local economies.

Multiple living wage reports suggest that many workers at Bowdoin may not meet a living wage, depending on their household arrangements.

A 2010 Maine Department of Labor report said the hourly living wage for a single parent of one in Cumberland County was $19.81. The wage for someone in household with two earners and two children was $14.30 per hour—nearly half of respondents reported earning less than that.

A 2017 study conducted by researchers at MIT says that the Maine living wage for a single parent of one is $24.21 and the wage for someone in a household with two earners and two children is $15.82.

Bowdoin’s decision to supplement low wages with a strong benefits package appears to be working for the College. Housekeepers and groundskeepers uniformly reported staying for the benefits. Some also talked about enjoying the work environment and the ability be around students.

One housekeeper interviewed said that because he appreciates the students, he took a two-dollar pay cut to an hourly wage of $10.50 to return to Bowdoin after having left originally to work at Walmart.

Bowdoin does offer good benefits, compared to other low-wage employers. Employees have access to subsidized comprehensive healthcare plans, which include dental and vision, life insurance, subsidized retirement accounts and paid time off including short- and long-term disability. The College also grants employees paid sick time and vacation time.

“Benefits, I will definitely say, are a positive,” said Icangelo. “Even the dentist now is covered. That aspect of this is the best I’ve seen in any other job I’ve had.”

Bowdoin employees are also guaranteed a full 40-hour work week, something not always available at other low-wage employers.

A raise for new workers but not veterans

Low wages present challenges, but housekeepers and groundskeepers interviewed unanimously revealed their current frustration with the fact that some 10-year employees are paid just 50 cents more than many new employees.

Five respondents to the survey who have worked at Bowdoin for over eight years report earning less than $15 an hour. Two workers who have been at Bowdoin for almost 10 years report still earning an hourly wage between $12 and $13. In order to accommodate the rising minimum wage in Maine, at the beginning of this year Bowdoin raised its minimum starting wage to $12 per hour, meaning all new hires earn less than one dollar less than these 9-year veterans.

“I don’t think that somebody that’s been working here for 10 or 11 years should be at the same pay rate as someone that’s just starting here. That just doesn’t seem fair,” said Bouchard.

The lack of parity comes from the fact that, when the College raised wages for new hires, it didn’t push veteran workers up accordingly.

“It’s called compression,” said Spoerri. “We used to have a dollar difference or 50 cents, but the fact is, now with this moving up so quickly, that compression is going to be the case.”

There is a ladder of positions in each facilities job. In housekeeping, new employees are often hired as a Housekeeper I, but with experience and time, can become a Housekeeper II or a Senior Housekeeper. Groundskeeping has the same position rankings.

However, many in housekeeping and groundskeeping feel that the ladders aren’t successfully increasing compensation and fully rewarding commitment. With the jump from I to II comes an increase of about 50 cents in hourly pay, according to Spoerri. The next jump to Senior Housekeeper or Groundskeeper brings about a dollar more in pay.

Nine respondents who have been at the College for over 10 years reported that they struggle to make ends meet. Three respondents reported that they might or might not struggle.

“My biggest problem here is that people who’ve been here for 20 years should not be struggling financially,” said Shawn Gepfert, a manager in the groundskeeping staff. “For guys who just start who are 18, 23, 25 years old, 15 an hour is pretty good. But a guy my age who is 40, 45, who’s been working here for 10 or 20 years—he shouldn’t have to struggle.”

Annual raises for all facilities workers are on average 3 percent of their wage, according to Orlando. For a housekeeper making $13.09—the average wage reported by survey respondents who work in housekeeping—that equates to 39 cents annually.

However, there is some wiggle room. Direct managers have discretion about their workers’ annual raises. Depending on performance, workers can receive anywhere from no raise at all to four percent a year.

For Gepfert, it’s frustrating that he can’t reward his crew with better compensation. There just isn’t any money available for him to allocate. “It doesn’t matter what I give them for a review, the raise is essentially the same. Three percent. When you’re three percent of 15 an hour, it’s not a whole lot of money,” he said. “I couldn’t give someone a good review and say they get four percent, and someone else gets two, but we’re talking pennies.”

Many workers, it appears, were given a two percent raise or less last year. Survey data suggests at least ten. Three workers said they received no raise at all.

According to Orlando, the money for larger increases just isn’t available. He says finding it conflicted with other budgetary concerns, like providing financial aid and providing good benefits to all employees.

“We do the best we possibly can to advocate for our employees,” said Spoerri. “We advocate every year. We did not have to go to 12 an hour. We could still be at 11 dollars. We go to Clayton, but the thing is, is how much does it cost us? Because it’s more in benefits, because it’s more in paid time off, in disability, in retirement. Retirement is based on how much you earn. Every time you continue to do that, there’s this exponential cost associated with it.”

Housekeepers also expressed anger that certain student employees make the same as them or their colleagues. In general, student wages are set below those of full-time employees. This year, guidelines for students’ wages range from $10 to $11.75 per hour. However, some positions may pay more. Students who work as interviewers in admissions receive $12.50 an hour.

”That’s not fair,” said Bouchard. “It makes you feel underappreciated. Especially when you’ve been here long.”

Work not respected

At Bowdoin, housekeepers are responsible for cleaning up vomit. It’s one of the ways in which housekeeping is an intrinsically difficult job. The repetitive motions of mopping and scrubbing and dusting all take a toll on the body, too. Housekeepers frequently report injuries—10 of 12 housekeepers who answered the survey question said they had been injured from working at Bowdoin, reporting strained muscles, chronic tendonitis and pinched nerves among other injuries.

In interviews, many housekeepers felt that their hard work and physical sacrifices are not only not respected by the College with monetary compensation, but that sometimes they are denied basic decency from their managers or HR. They report being reprimanded and feeling unheard or undervalued.

Sometimes, it’s the small things, like when housekeeping staff were not alerted about a snow day until they had already arrived to work at 5 a.m., even though students were notified the night before—Spoerri says she hears from housekeepers regularly about this. But for many, these feelings stem from specific incidents, often a few years back, under a manager who was later forced to retire. Since then, under a new manager of the housekeeping staff, employees have reported fewer complaints.

For example, around five years ago, a housekeeper working in the basement of Coles Tower passed out. Her partner thought she was having a heart attack and called 911 immediately. However, instead of concern for her colleague’s wellbeing, she was sent to HR and reprimanded her for breaking College policy by calling 911 before Security. In the future, she was supposed to wait for Security to assess before calling 911.

Ann Basu

Ann Basu“I don’t know why it matters because the phones on campus, if you call 911, Security gets alerted,” she said.

After this story was originally published, Director of Safety and Security Randy Nichols clarified that the College does not have a policy against calling 911 before calling Security.

Multiple interviewees also expressed concern that they are watched on camera by Security at the request of their bosses.

“There have been occasions where a department head or director gets information that an employee isn’t doing what they’re supposed be doing and they would reach out to us to investigate. While that doesn’t happen often, it’s not something that doesn’t happen,” one Security officer told the Orient.

After inquiry by the Orient into this practice, Orlando confirmed that the former housekeeping director routinely accessed the Security communications center in Rhodes Hall with the help of a Security officer.

According to Orlando, neither he nor other administrators knew about this practice until the Orient’s inquiry, but both individuals involved have since left the College.

“Basically the activity stopped with [the officer] who was basically a bad egg in the Security office,” Orlando said. “It’s deeply troubling that this this took place at all.”

One housekeeper, who was tasked with cleaning Rhodes Hall at the time and who asked to remain anonymous, said she witnessed this practice first-hand.

“Say I was in the Security office, vacuuming or pulling trash or something. Our boss at the time would come in and ask me to leave so that she could watch the security cameras. She didn’t tell me that, but the security officers, when I’d go back in and finish, did: ‘Well she comes in and wants us to pull up cameras from different areas so she can check up on you guys.’”

While regular surveillance doesn’t continue, the practice of monitoring employees via camera may still occur, occasionally, in the cases of employee investigation.

“If we are asked to do an investigation, we do, generally,” said the officer who spoke with the Orient.

The possibility of being watched sends a message to housekeepers that they are not trusted to perform their jobs independently. In addition to not feeling trusted, housekeepers report not feeling heard, especially by HR.

Multiple employees reported having to beg for promotions from HR. Under the old manager, who many housekeepers found to be harsh and punitive, it took a chorus of voices complaining to HR before their concerns were taken seriously.

Housekeeper Sonya Morrell was one of the employees who spoke up about the manager early on. “In the beginning it was, ‘Here come the troublemakers,’ but then more people started speaking up. You can’t keep saying, ‘Oh it’s this group and their trouble.’”

When asked about workers not feeling heard, Spoerri dismissed their complaints as those of a few disgruntled employees.

“I could probably list off who they are,” she said. “People lose perspective. They get here and get a little entitled and whatever. I get that we’re not an perfect employer. I don’t have perfect managers out there. God knows I don’t have perfect supervisors. But given the overall… Seriously?”

“Human Resources, whether it’s at Bowdoin College or at Bank of America, is here to protect the company,” said George Hale, a groundskeeper who has worked at Bowdoin for almost 23 years. “I know on the students’ end, this college is a non-profit … common good. But in a facilities, dining service angle, it’s a company. We work for a company. And HR is here to protect that company.”

This is a feeling shared by many employees. They can talk to HR and their managers but in the end, the higher ups are not here for them.

Are you a support-staff employee at Bowdoin? We want to hear about your experiences. Send us a message anonymously here.

One result of this is that many feel and know that they are replaceable. A few report having been told this directly.

“Just being here for 17 and a half years, I’ve seen so many people come and go. I know how replaceable we are. It’s sad to say,” said Jane Davis, a housekeeper who currently works in West Hall.

Unequal benefits

Facilities staff say that they love Bowdoin students. The students are one of the reasons why they work here—they enjoy being around and serving so many talented and kind individuals. Several housekeepers said that students are their biggest supporters on campus. They say “Hi,” and sometimes develop relationships, since many spend much of their time cleaning first-year dorms. Some even keep in touch after graduation. However, interviewees say that they don’t receive the same respect from faculty and other College staff. On the hierarchy of employees, housekeeping is squarely at the bottom. Other staff make that clear to them.

“It’s the—no-offense—professors, the other adults who work here, they sometimes treat us as if we are that bottom totem pole type of thing,” said Icangelo.

This surely isn’t an attitude held or expressed by all employees at Bowdoin, but it is reflected institutionally in the benefits workers receive. As a percentage of their income, lower wage workers pay more for health insurance at Bowdoin than do higher earners, despite the fact that the plan prices are split into four income tiers. With the wages they make and on top of other expenses, this can be a significant burden.

For the same middle-priced health insurance package, an employee with a family who makes the average housekeeper wage will spend 12.3 percent of their income on their monthly plan, whereas an individual making the average faculty salary will spend 2.4 percent of their income.

Vacation time and other paid time-off policies are another area in which lower wage workers receive worse benefits.

Administrative staff, which ranges from deans to administrative assistants, are granted 20 days per year of paid vacation time, while support-staff members receive 10 days in their first year of employment, 15 days in years two through seven and 20 days after eight years of employment. Faculty have no defined vacation, though they are afforded paid time off for family leave.

In addition, rules for short-term disability insurance, which covers 70 percent of employees’ wages in the event of temporary impairments, are severely unequal. When applying for short-term disability, staff members are subject to a 14-day waiting period that faculty members do not encounter. As such, an impaired worker has to use vacation and sick time to receive an income during those two weeks.

Multiple housekeepers said that they feel discouraged from actually using their paid time off. Using all of the sick days can be seen as an indication that the employee is lazy or not taking the job seriously.

“Sick days seem adequate, [but] its being penalized for how many you use that’s the problem,” said one housekeeper who asked to remain anonymous.

“We encourage employees to keep a bank of sick time and vacation time,” said Spoerri. “If you’ve been here 5, 6, 10 years, you shouldn’t be at a low vacation or sick time balance.”

Another crucial differential between resources available to support staff and faculty and administrative staff is childcare. The Bowdoin Children’s Center is a world-class daycare and preschool located behind Thorne Hall on South Street.

The Center has four separate programs—for infants, young toddlers, older toddlers and preschoolers. It is open to all employees and strives to integrate itself into the community, according to its mission statement.

However, not one support staff employee has sent a child to the Center in the past six years, according to Martha Eshoo, its director. The Center does not seem to be designed with all Bowdoin employees in mind. The main factors preventing the children of support staff workers at Bowdoin from enjoying the Children’s Center are its hours and tuition cost.

Most workers in housekeeping are required to arrive at work at 5 a.m., while workers in groundskeeping are required to arrive at work at 7 a.m. However, the Center does not open until 7:45 a.m. There’s little flexibility in this, says Eshoo.

Enrollment at the Center costs between $1,000 and $1,160 per month, depending on the child’s age. HR has a program that gives a limited number of employees a 25 percent discount on tuition, but even at $750 per month, the cost of care would be 33 percent of the average reported housekeeper monthly wage, assuming no overtime and a 40-hour work week.

Without this benefit, Bowdoin employees are forced to be creative about finding care for their young children.

When Children’s Center told Hale that they would not be able to accommodate his hours years ago, he found a different solution.

“You know who stepped up? The Bowdoin hockey team. They lived at Brunswick apartments. I said guys, just chill out with him. Those guys, all seven of them. They figured out a system and a schedule,” he said.

Others pay for childcare elsewhere.

“It was another mortgage payment. You make concessions on other things in your life while your kids are at daycare,” said Gepfert.

If you took them away…

After last weekend’s Ivies festivities, the campus was littered in trash from students’ partying—the Brunswick Apartments Quad, Reed House’s backyard, the lawns next to MacMillan, Quinby and Ladd Houses and the common areas of dorms. But by Monday afternoon, these grounds were returned to their normal state of cleanliness. Housekeeping and groundskeeping make Bowdoin run, and the College knows this.

While Ivies, reunion and graduation are especially important weekends, support staff works year-round.

“In some aspects it seems like a menial job. We’re not making policies for the College. We’re not teaching,” said Morrell. “But if you took us away, and got rid of the housekeeping staff in general, this college wouldn’t be what it is.”

Editor’s Note May 4, 2018: This story has been updated to include a comment from the Director of Safety and Security clarifying the College’s policy about calling 911 in case of emergency.

Editor’s Note May 5, 2018: Early this morning, the College published a response to this article.

Correction May 6, 2018: An earlier version of this story incorrectly stated that housekeepers work 11.5 hour days during their period of mandatory overtime between exams and reunion. During this period, they are required to work 10 hours per day at most, though can sometimes elect to work more.

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy:

- No hate speech, profanity, disrespectful or threatening comments.

- No personal attacks on reporters.

- Comments must be under 200 words.

- You are strongly encouraged to use a real name or identifier ("Class of '92").

- Any comments made with an email address that does not belong to you will get removed.

Writing like this is the real value and purpose of the Bowdoin Orient. Thank you Bowdoin Orient for publishing this important story. Bowdoin brags about the Common Good and Social Justice but pays many of its most crucial workers an unlivable wage. A year at Bowdoin costs three times as much as one of these workers makes. That is shameful.

This is the same institution that pays its chief financial guru over $1M a year. Why can’t Bowdoin pay those support workers a decent wage?

Excellent reporting on the financial struggles of the working class that keep an elite institution (Bowdoin) running. I regularly see house cleaners in my acupuncture practice. The repetitive strain of this kind of work consistently breaks down bodies over time, but in the current economy, low wage workers are seemingly viewed as expendable and wages are kept low based upon a market economy which places profit over life.

Equally disturbing though are reports of facilities staff being ignored or looked down upon by professors and white collar employees. Over time, this has a negative psychological toll which also adversely affects physical health. Everyone has a basic need for respect and kindness. Bowdoin: Time to rethink our commitment to the “Common Good”.

Best article in the Orient in years. Truly stellar work, you should be proud!

Hats off to you, Mr. DiPrinzio, for the best journalism I have seen in the Orient in three years. Real people with a real life problem that Bowdoin contributes to and can do something about. Wouldn’t it be wonderful if some of your classmates would take a break from bashing one another to take up this cuase. And finally, let’s hope that faculty and administrators will take a moment to reflect on their responsibilty as role models to the young adults they mold and undertake to be better.

Recently, the CEO at my non-profit decided that she would institute a progressive system of health insurance payments so that now our lowest-paid staff pay an equal proportion of their income on this expense, (rather than equal cost) and our highest paid staff now pay much more as a result, with no complaints and an understanding that we are doing what is right. The tone is set from the top, Bowdoin. We can do better!

Thank you for this article and your thoughtful reporting. I wasn’t too surprised to learn the extent of the wage inadequacy and inequity amongst housekeeping and groundskeeping staff (and I believe the inequity extends further into other crucial hourly staff positions that keep the college running). What truly surprise and disappoint me are Tama Spoerri’s condescending comments and poor explanations for college pay scaling, and her weak justification for wage “compression” (which sounds to me like a systematic cutting of costs by freezing wage increases for the lowest earning group of college employees who have also been here the longest… it makes almost no sense).

I hope this issue gets student and alumni attention, since Bowdoin is highly accountable to you. Bowdoin provides so much for its students and its broader community, but it needs to provide significantly more to the folks who keep everything running. Bowdoin is a far more complicated and multifaceted operation than a Walmart or McDonald’s, and should treat employees at all levels with more trust and appreciation (and it can start by increasing pay).

I hope this article ignites change. If you’re an alum, and you think every Bowdoin Employee deserves a living wage, consider signing and sharing this open letter:

https://docs.google.com/forms/d/e/1FAIpQLScGWQ3SM-PJd6tydTOwOqLdEvmgIG-9nRm03GUAFDPm7JDE8w/viewform

This was an excellent article; thank you. I’m dismayed that facilities employees at Bowdoin aren’t earning a living wage. The HR director’s comments in the article seemed dismissive and condescending. I’d love to see some labor organizing on campus, and leadership (in HR and elsewhere) more in touch with the lived experience of employees. Bowdoin can do better.

Excellent work Harry. Very informative and timely.

Another thing I find frustrating is the blanket three percent raise. It doesn’t matter if you are a hard worker or not, we all get the same percent raise. This takes the initiative to work hard and have pride in your work away. Why go the extra mile when you won’t be rewarded for it?

Alumni, parents, students, faculty, and staff,

Show the college that you call for a living wage for Bowdoin facilities workers by signing this petition.

https://bowdoincollege.qualtrics.com/jfe/form/SV_9Qs73NKEOE83Ogl

A fine piece of investigative journalism, leaving us readers with a lot to think about. Thanks, Harry!

I am an alum and former staff member and I know this isn’t the first time these issues have come up. The College did a review of all support staff positions in the ’80s, adjusting many job descriptions, pay grades and resulting salaries. It was a long and arduous process, but made everyone on campus, including the students who worked for us and the faculty and salaried staff who saw us go through it, re-think the value of each and every worker, the college’s responsibility to the staff — within the available budgets, of course — and how to reward those who went above and beyond the call. Maybe it’s time for another overhaul. Fellow alums, remember when you make your annual support pledge, that available budget is all part of the issue. We (staff, faculty, alumni and students) are ALL part of the Bowdoin family, and ALL staff members contribute to each student’s education; it’s important to remember that.

I too wish that there were less poverty in the world. But Bowdoin is a non-profit with an educational mission. Bowdoin already offers above market compensation to staff, and it would be wrong to further dilute Bowdoin’s educational mission by paying even more. Saying Bowdoin should pay staff more is the same as saying that the College should spend less on education. How would you feel about Oxfam offering well-above market pay to its employees, thus depriving the needy across the world?

How much endowment does Bowdoin College have available to them? $1.63 Billion. For a place that preaches endless social justice leftist ideology it appears that “justice” stops when it applies to them. Keep the fantasy land running for the kids and professors, just ignore those other people that run around behind the scenes making $12.50. Although higher education institutions are mostly non-profits, their goal is not education. Education is what they sell, making money and gathering funding to keep the grand halls open is their mission.

This is an impressive piece of journalism– factual, balanced and well- researched. In light of the role that the facilities and groundskeeping staff play in maintaining the beauty and cleanliness of the college, it doesn’t seem too far-fetched to say that they could be better compensated for the work that they do. As a Bowdoin parent, I would certainly notice a tremendous difference between a clean and attractive campus and refuse-strewn, unkempt lawns and buildings. These aesthetic issues are much more important than they may seem. The staff literally provides the all-important first impression to potential students and parents who are visiting the campus throughout the year. The staff , then, should be rewarded for their contribution to Bowdoin’s excellence– through respect from professors and students, and through more-generous wages for dedicated and veteran employees.