Long division: Polarizing parties, formulaic discussions & their confusing remainders

April 13, 2018

Diana Furukawa

Diana FurukawaThis article is the third installment in the Diversity Matters series, in which students from the Diversity in Higher Education seminar present research based on interviews with 48 seniors. To read the first installment, click here. To read the second installment, click here.

Our analyses of self-segregation and insufficient race education at Bowdoin suggest that many students do not understand the impact of racial inequity in their own lives. What happens when this manifests in controversy?

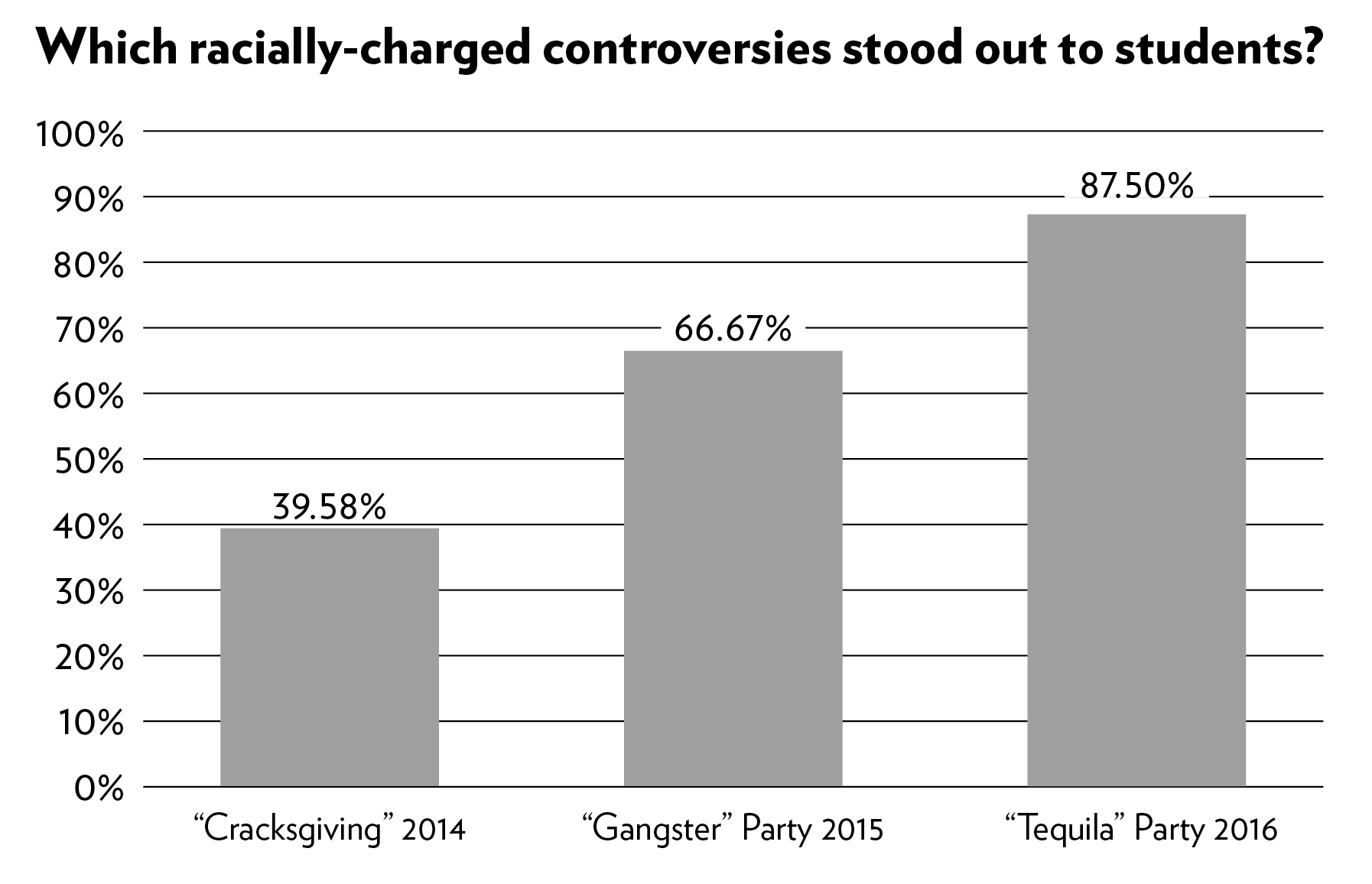

At the beginning of the Class of 2018’s college careers, three racially charged controversies occurred on campus over the course of 15 months. In their first semester at Bowdoin, just before Thanksgiving, the men’s lacrosse team hosted their “Cracksgiving” party, an annual event at the time where teammates and their guests dressed up as Pilgrims and Native Americans. The following October, members of the sailing team dressed up in baggy clothing, one member wearing cornrows, for their “gangster” party. Four months later, a group of students threw a tequila-themed birthday party in an upperclassmen dorm in which some students wore mini sombreros. While less than half (40 percent) of our interviewees mentioned “Cracksgiving,” almost everyone (92 percent) mentioned one or both of the sophomore year controversies.

COMPILED BY HANNAH DONAVAN AND DREW MACDONALD. SOURCE: “UNDERSTANDING DIVERSITY”.

COMPILED BY HANNAH DONAVAN AND DREW MACDONALD. SOURCE: “UNDERSTANDING DIVERSITY”.The unique, rapid succession of racially-charged controversies—especially during the 2015-2016 academic year—engaged students across campus in issues of diversity, including many who had before not done so. These events catalyzed discourse on race, cultural appropriation and campus structures, and the campus climate grew turbulent and divided as the College responded to these issues. For many current seniors, this tone defined their second year at Bowdoin and has had lasting effects.

Our research shows that individuals’ responses to these racially-charged controversies cannot fit into simple categories—they cannot be understood, as one student said, as “an us-versus-them binary.” We found that some students report learning from the aftermath of these parties and many report feeling discouraged by this series of events. Students felt pressured to talk about the parties and were often unsatisfied by their peers’ and administrators’ reactions. We explore how students have tried to reconcile their lingering frustrations and find common ground with those whom they perceive to be on “the other side.”

•••

In this climate, many of our interviewees expressed a desire to resolve their confusion. More than half (58 percent) mentioned encouraging learning experiences that helped them understand the controversies. They often noted the value of being able to ask questions openly and form new conclusions and ideas they could apply to other areas of their lives. To many students, classrooms were crucial sites of these conversations. To others, talking informally with friends and peers who were more engaged in the issues helped alleviate confusion and illuminate others’ perspectives. For example, one student explained not knowing what cultural appropriation was—apart from being “bad”—until an upperclassman heavily involved in the discourse explained it.

Even students implicated in these controversies described experiences that encouraged them to opt into discussions about race. One student described their team’s conversations with an affinity group as “the most productive conversation we had” because the group was understanding and did not assume bad intentions. However, encouraging learning experiences were not universal.

A central pattern among students who mentioned feeling discouraged (63 percent) was the lack of platforms to ask questions without feeling punished by their peers. Twenty-three percent of discouraged interviewees expressed unresolved confusion. Students of color in particular commonly felt they were expected to know, care and teach more about cultural appropriation than their white peers—yet did not always feel prepared to do so. One student explained “I still don’t feel like I can do the best job explaining to someone why [cultural appropriation is] not a good thing.” Another student said, “I remember that year really realizing that I could say that I fit in, in terms of being a person of color, but, culturally, I’m very white,” indicating that they still felt ignorant about cultural appropriation.

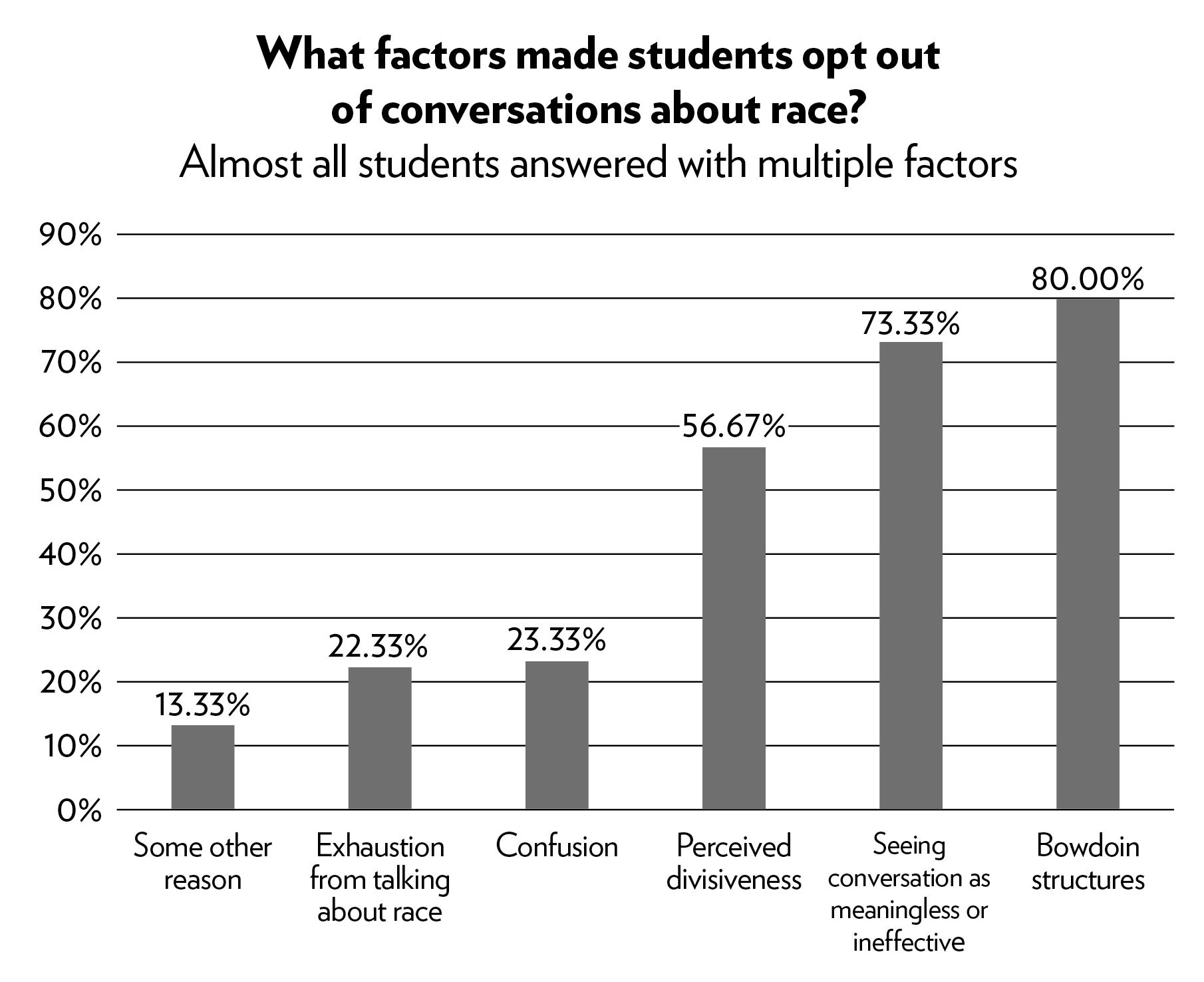

COMPILED BY HANNAH DONAVAN AND DREW MACDONALD. SOURCE: “UNDERSTANDING DIVERSITY”.

COMPILED BY HANNAH DONAVAN AND DREW MACDONALD. SOURCE: “UNDERSTANDING DIVERSITY”.Following the “tequila” party, the campus felt polarized, much as it does to some students today. Fifty-seven percent of discouraged students mentioned polarization and felt divisiveness. One student said, “I realized how divided our campus could be in so many ways, but [after the ‘tequila’ party], I really felt it.” Another student explained how the controversy “made Bowdoin feel so divided and you had to choose a side … it was really hard because I could totally see both sides, so it was almost impossible—I felt so divided,” they said. Similarly, one recalled walking into an open Bowdoin Student Government (BSG) meeting following the “tequila” party: “I’ll never forget this: literally all the minorities were on one side of the room and it was all white people on the other side of the room,” they said. “I feel like everyone was waiting for me to choose a side.”

•••

Why do students still feel confused and divided, despite their desire to find a resolution? After the “tequila” party, a number of community forums were held on campus by BSG and other official groups, in an attempt to help students process the controversy. Despite the purpose of prompting open conversations and learning, these reactive discussions felt to some students like “echo chambers” where the same strong opinions were validated and others silenced.

Students who felt constrained in structured conversations felt obligated to maintain “political correctness.” For example, one student involved in one of the controversies said, “It felt like there were targets on all our backs and everyone was watching out to see what we did next … Nobody wanted to say the wrong thing.” Similarly, another student mentioned fearing their inquiry would infuriate their peers: “We were all too scared to ask people why they were upset about it, because all we had seen was angry Facebook posts and yelling at the [BSG] meeting.” One student of color, who was in disagreement with members of their affinity group, said, “I felt like I couldn’t speak my piece without being attacked.”

Confusion about the racially-charged events was common, but questions were rarely asked—much less answered—in these structured conversations. Interviewees felt restricted to specific ways of talking about the controversies at public discussions and few felt comfortable expressing their opinions or acting upon their confusion. Together, polarization and confusion hindered efforts to learn.

Each party was quickly “universally condemned” in BSG resolutions that defined cultural appropriation and asserted that it was “unacceptable.” Disciplinary sanctions by the administration after the “tequila” party described the behavior as “unbecoming of a Bowdoin student” and specified punishments for implicated students. In this way, Bowdoin officially presented a unified front maintaining that the incidents were unacceptable—but as many seniors recall, students’ interpretations remained divided. The administration expected students to understand where to draw the line with respect to cultural appropriation and ethnic stereotyping but students did not feel that they knew where this line was.

This formal denouncement of cultural appropriation on a campus where students generally lack racial education generated resentment. Attempts by the College to respond appropriately to the controversies were often met with bitterness. First, students in general were confused about the nature of and reasoning for the punishments. Second, some students felt they were disciplined without enough explanation of the line they crossed, nor sufficient opportunity to talk with the group on the other “side” of the conflict. Some complained of a lack of transparency and a focus on assigning blame. As one student said, “The way it was handled seemed like really kind of inflammatory, and [the administration was] not helping settle disputes or create meaningful apologies.” One student described the punishments as arbitrary. Students talked about punishments, polarization and conflict that led to resentment, which ultimately discouraged them from engaging in and learning from racial discussions after the events.

•••

If divisiveness is the one thing students agree on, how can they come to a solution that brings understanding and healing to all parties? The frustration evident in our interviewees’ stories more than two years after the “tequila” party is a testament to the controversies’ enduring sting. What does it mean for so many seniors to graduate with the memories of division still intact? As the class of 2018 prepares to leave Bowdoin, so too may the memories of these racially charged controversies. Pamela Zabala ’17 explored this issue in her honors thesis, which we encourage you to read. Her research revealed incidents of racial bias have occurred on average every 3.5 years since 1964—just about every time the student body is regenerated. It should not take another “gangster” or ‘“tequila” party for future Bowdoin students to care and learn about racial justice.

How, then, can students learn—as many said they wanted to—from these moments?

Some of this work starts with the teams implicated in the controversies. As one sailing team captain shared, post-“gangster” party, they met with sociology professors and participated in a facilitated Inter-Group Dialogue (IGD) with members of the African American Society. This year, they held an IGD program in addition to a team conversation about the “gangster” party to give underclassmen the context that prompted the team’s conversations about race. A member of the team said these events “try and emphasize that the conversations about race extends beyond the ‘gangster’ party.” In contrast, a member of the men’s lacrosse team said that he participated in “very productive” discussions after “Cracksgiving,” but the team has not participated in any formally organized discussion about the event since. These students were drawn into discussions about racial justice because they had to be. Their learning matters, but the rest of campus must work, too.

Classes of 2019, 2020, 2021 and 2022, recognize your power and duty to learn during your time here. Our research shows that coursework and class discussion on racial inequity can effectively teach students about race without burdening students of color. There is no reason a Bowdoin student should graduate without a grasp of institutionalized racism. Consider this as you register for fall classes. Professors, make teaching these controversies part of the education you provide your students.

Seniors, ignorance is no acceptable excuse. Carry the lessons from these controversies with you—if you have lingering unresolved confusion, ask yourself why, and if there is anything you can do to learn. Listen to what your peers have to say, and consider discussing over brunch and beyond.

Next time, we will close our series by looking at what seniors think about diversity. We will consider the personal meaning of diversity for students and seek to answer why diversity matters at Bowdoin.

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy: