Jose Antonio Vargas discusses immigration, discomfort and finding home

March 2, 2018

Tessa Epstein

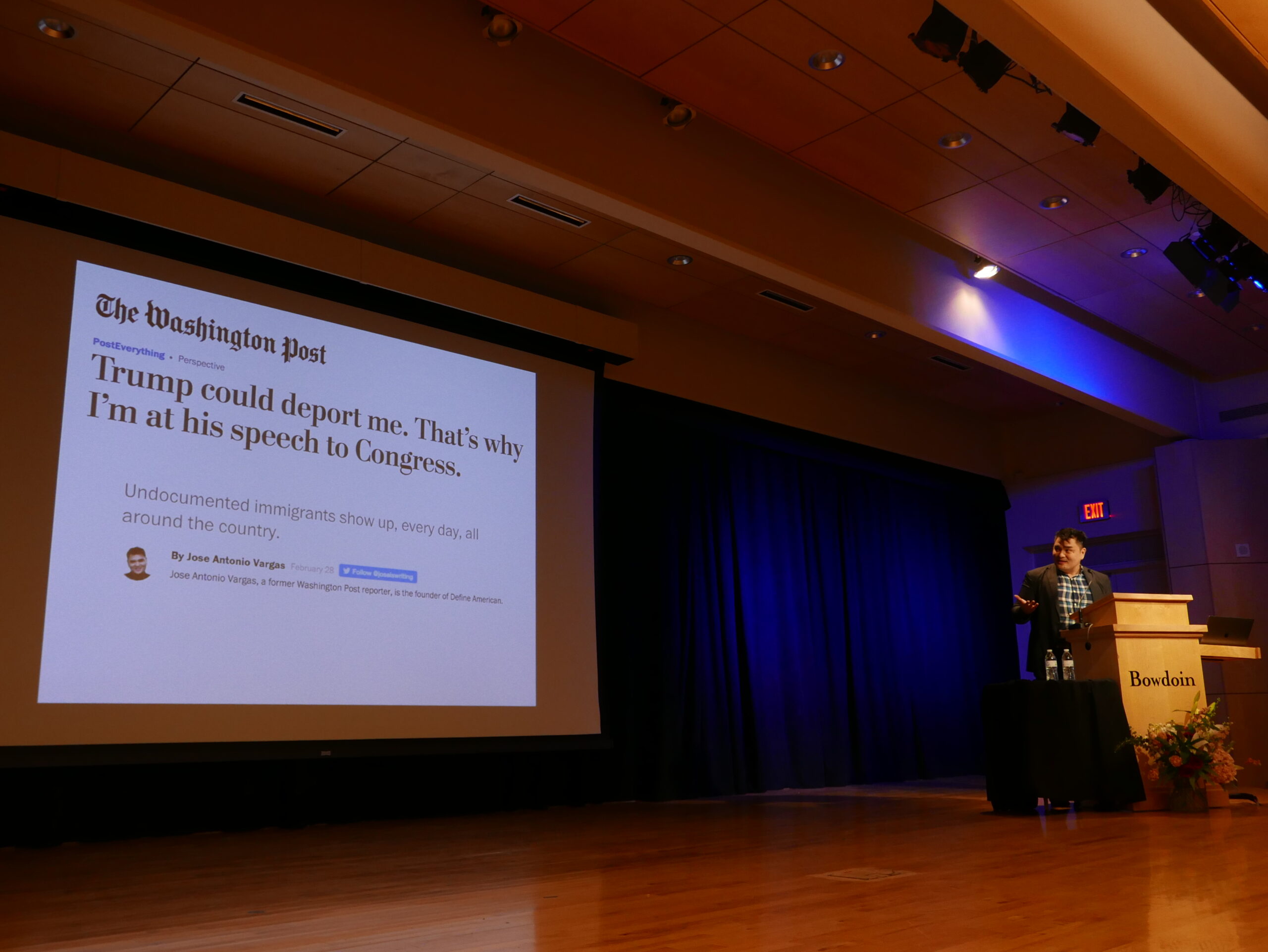

Tessa EpsteinJose Antonio Vargas is home. His California driver’s license may look a little different than a citizen’s, but—in front of a packed Kresge Auditorium last night for the Kenneth V. Santagata Memorial Lecture—he shared his personal struggle to feel like he belongs in America as an undocumented immigrant, and he challenged Bowdoin students to undertake the uncomfortable conversations necessary in today’s immigration debate.

Vargas, a Pulitzer-Prize winning journalist and filmmaker, came out as undocumented in a 2011 essay published in New York Times Magazine. He said his training as a journalist strengthens his desire to understand other perspectives, even those of people who think he doesn’t belong in America.

“I was always asked to make sure that I don’t think of an issue or a person from just one point of view,” he said in a phone interview with the Orient prior to the event. “That my reality is not the only reality. And that my truth is not the only truth. It’s always in relation to other people.”

Vargas has appeared on Fox News, debating hosts like Tucker Carlson and Bill O’Reilly. He said he’s accepted over 100 invitations by Republican groups—even though he’s witnessed some individuals call Immigrations and Customs Enforcement (ICE) while he’s speaking at their events.

“I engage as many people as I can who don’t agree with me because I feel like if I’m going to get anywhere, then I have to figure out why to them the sky is black when to me the sky is white. I have to figure out, how did they get there?” he said. “And that’s the thing, I’m fascinated by a lot of the anti-immigrant, naked bigotry.”

For instance, Vargas shared how he decided he should probably move out of his apartment when the super for his building told him the building couldn’t hide him if ICE ever showed up. As an undocumented public figure, he can’t avoid the discomfort. Instead, he’s sharing it.

“I have been uncomfortable since I found out that I wasn’t supposed to be here. I feel like all I’m doing is sharing the uncomfortability,” he said during the lecture.

He continued, “I get really frustrated with this woke identity which has been going around, which means that all you gotta do is say the right thing and talk to the same people to be woke. That you don’t have to challenge yourselves to confront and face people who don’t share the same perspective and point of view as you. That it’s much easier to call out strangers on social media than deal with your racist parents. Or your racist grandparents. Or your racist co-workers.”

While conversations about immigration might be uncomfortable, Vargas sees the importance in stopping misinformation. He noted that immigrants actually commit crime at a lower rate than native-born Americans. He also pointed out that undocumented immigrants contribute $13 billion to Social Security each year, helping keep the program solvent even though they do not receive benefits themselves.

He argued that the United States has yet to reconcile with its complicated immigration history.

“Immigration is probably the most discussed and yet least understood issue in America,” he said. “Talk about a wall—we have a wall up about our own history. And I’m fascinated with white Americans who don’t want to face their own history.”

As a Filipino immigrant, he noted that the large presence of Filipinos in the United States can be traced to the American colonization of the Philippines after the Spanish-American War in 1898. The United States maintained the Philippines as a colony until 1933.

Vargas also drew similarities between Irish immigrants who came to the United States when facing starvation in the mid-1800s and Central American immigrants who try to come today. He noted that U.S. immigration restrictions weren’t invented until over a century after the nation’s founding—at first, the country accepted all immigrants.

“Unless you’re a Native American or an African-American, three questions must be asked: Where did you come from, how did you get here and who paid?” he said. “If you can’t answer those three questions, you have no right to talk to anyone about a border that you don’t understand.”

Vargas understands borders, although it’s been a while since he’s crossed one. As an undocumented immigrant, he would not be allowed back into the United States if he left. There is not a pathway to citizenship for him, nor anyway to legalize his status. But he has made his home in America.

“If they’re going to ask me to leave, they’re going to have to drag me out of this country—with all of my furniture from Pottery Barn,” he said.

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy: