Eating disorders at Bowdoin: students share stories of pressure and anxiety

Eight students spoke with the Orient about their experiences with eating disorders. These are their stories.

March 2, 2018

Ann Basu

Ann BasuIn recognition of National Eating Disorders Awareness Week, the Orient spoke to eight students, who shared their personal stories and thoughts about eating disorders. One name has been changed to protect the identity of the student.

When Julia Morris ’19 came to Bowdoin with the class of 2018, she spent just three weeks at the College before she went on medical leave as a result of her struggle with anorexia nervosa.

Morris started having disordered eating thoughts when she was in second grade and since then, she has gone through phases with anorexia. She started seeing a doctor when she was 11 years old, but it wasn’t until she got to high school that her eating disorder significantly affected her life.

“When I relapsed when I was 15, I never really came out of that,” said Morris. Her disorder worsened upon her transition to Bowdoin.

“My weight was too low, and I wasn’t dealing with being here well. I wasn’t dealing with being away from home,” she said. “It sort of got to the point where people started to be concerned for my health, so I went home.”

During her time off, Morris was admitted to an in-patient treatment center. When she came back to Bowdoin, she re-matriculated with the class of 2019.

According to the National Institute of Mental Health, eating disorders—officially categorized as “illnesses that cause severe disturbances to a person’s eating behaviors”—have the highest mortality rate of any mental health disorder. Eating disorders include anorexia nervosa, bulimia, binge eating disorder and orthorexia, among many others.

What differentiates eating disorders from disordered eating thoughts is the severity and consistency of behaviors.

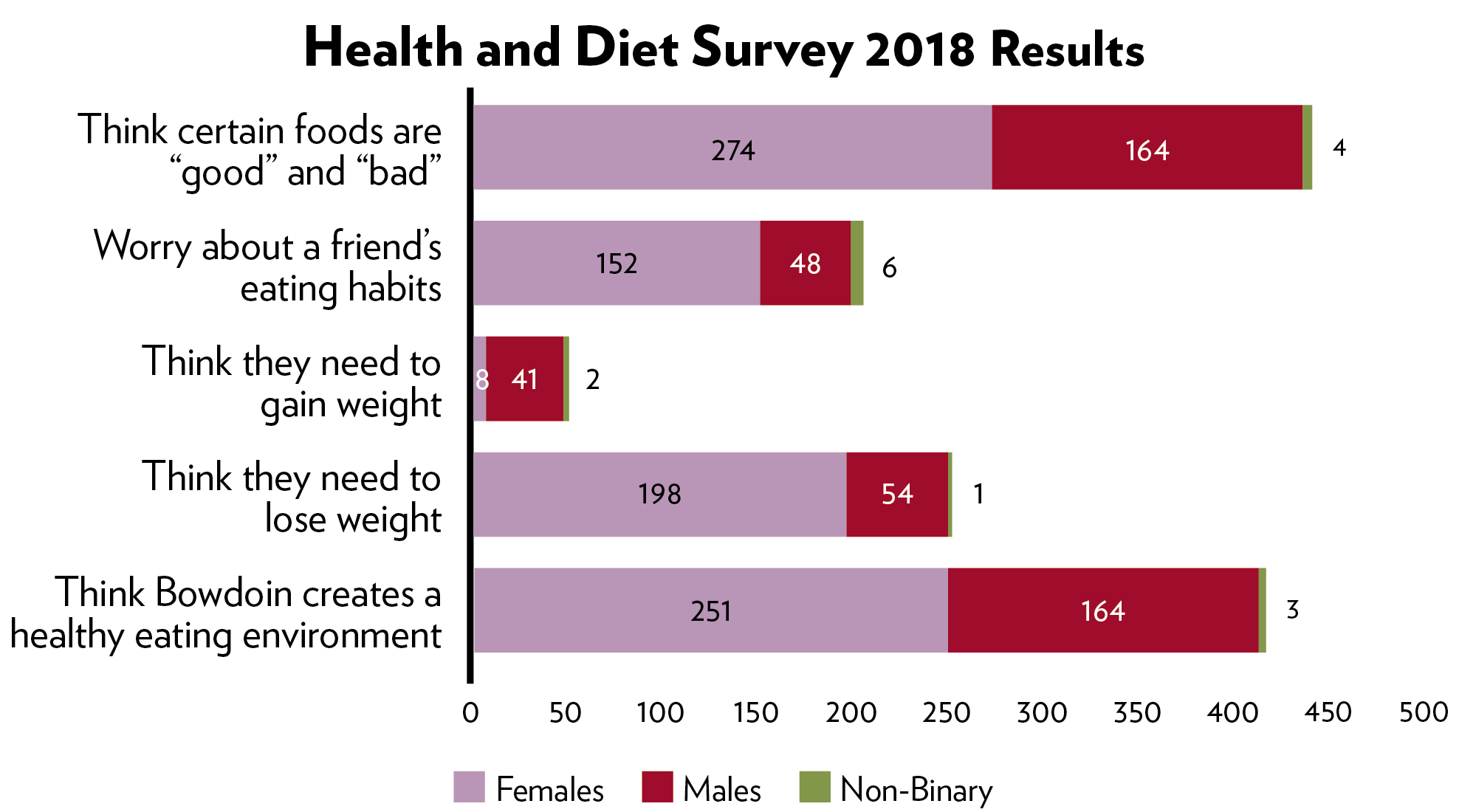

This week the Orient sent out its Health and Diet Survey—last distributed five years ago—to the student body. Of 538 respondents, 60 percent of women said they thought they needed to lose weight, while 45 percent of women were worried about a friend’s eating habits. Forty-three percent of all students said they exercised to compensate for food intake, and eight percent of students have been diagnosed with an eating disorder. All of these numbers represent increases since the last survey.

Hannah Donovan

Hannah Donovan“Part of the reason why I’ve been hesitant to accept [calling what I have an eating disorder] is my sister had anorexia nervosa,” said Megan Retana ’19. “I grew up with that and not understanding it.”

Retana has struggled with disordered eating thoughts since high school, but it wasn’t until her first year at Bowdoin that she began to understand what she was experiencing what many would classify as an eating disorder.

Both Retana and her sister were overweight growing up, as are her parents, which contributed to her low self-esteem.

“The feeling of starting college and losing weight was really exciting to me,” said Retana.

During her first year at Bowdoin, Retana saw counselors at the Counseling Center, but ended up switching counselors and felt like she wasn’t getting the support she needed. She was also diagnosed with ADD her first year and was prescribed Adderall, a side effect of which is loss of appetite.

“I was also having a lot of anxiety attacks and so there came to a point towards the end of the year where I was having anxiety attacks every day. It wasn’t sustainable,” said Retana.

Ann Basu

Ann BasuUltimately, after being hospitalized for a psychiatric crisis during her first year, Retana took a semester off and began to seek help for her eating disorder.

Coming back to Bowdoin, Retana has found support in seeing Dr. Kathleen Hart, a licensed psychologist who specializes in eating and anxiety disorders. She is working towards recovery and now considers her eating habits to be more or less stable.

•••

Recognizing a need for additional support for students with eating disorders, the Counseling Center reached out to Hart and since the fall of 2016, Hart has come to meet with Bowdoin students once a week. Currently, she is seeing around nine Bowdoin students, individually and in group sessions, who are struggling with eating and/or anxiety disorders.

Emily Conroy ’19 is one of the students Hart is seeing. She went to the Counseling Center to seek help for her disordered eating thoughts and behaviors during her first semester of her sophomore year, after which she was referred to Hart.

Conroy had disordered eating thoughts throughout high school, centered on poor body image and low self-esteem. After starting college and transferring from Barnard to Bowdoin, she realized the thoughts were becoming more persistent.

Similar to Retana, it took Conroy a while to admit that she had an eating disorder. It wasn’t until two months into seeing Hart that she was comfortable recognizing her illness and understanding the underlying factors.

Since seeing Hart both individually and in a group, Conroy has been able to grapple with her eating disorder more easily. The group therapy session offers support and a sense of belonging.

“[The biggest thing I get from the group is] realizing that other people feel similarly. Not in the same way, but I’m not going through it alone, which makes it much less scary and much more reasonable and you’re able to pin it down and tackle it,” said Conroy. “And hearing other people’s perspective helps me see things in a new light as well.

Retana echoed this sentiment. “It’s not nice to hear someone else say things that you’ve thought in your mind. It’s not nice to hear that they think that about themselves, but it’s nice to kind of know that you aren’t the only one who feels a certain way.”

Many students say they feel shame in admitting the disorder to themselves and others.

“I remember when I was in high school and I was going through all of that, my friend started packing extra food for me because she was like ‘You won’t feed yourself.’ But I never even told her anything that I was going through,” said Haley Friesch ’18, who has suffered with disordered eating since her senior year of high school.

When she came to Bowdoin, she said she gained a noticeable amount of weight as a first year, which reignited a cycle of calorie counting and dangerous restriction.

Friesch is one of Hart’s nine patients and is proud of the progress Hart has helped her make through guiding her nutrition and realigning the way she thinks about food. However, she still struggles on a day-to-day basis.

Ann Basu

Ann Basu“The biggest thing is that people think of eating disorders as somebody who is really skinny, and looks like they’re going to die, or somebody who has a binge eating problem and can’t control themselves and it’s such a spectrum. I know that nobody would look at me and think, ‘oh she has an eating disorder,’” she said.

“But it doesn’t change the fact that when I’m getting dressed, I’m nitpicking little stuff about my body or I’m always thinking about, if I eat this for breakfast, then I have to eat this for lunch. It’s so thought-consuming that you’re wasting a lot of mental energy that you could be expending elsewhere.”

•••

Several students interviewed cited Bowdoin’s rigorous academic environment as a stressor of their disorder.

“For me, it’s incredibly tied with an anxiety and it’s a coping mechanism. It’s a way to hold onto some semblance of control in a world that I really can’t control very much,” said Conroy. “It looks different at different times, depending on what emotional stress I’m dealing with.”

Conroy’s eating disorder is, in large part, a manifestation of her obsessive-compulsive disorder and wanting to control a part of her life amidst the stress and pressure of Bowdoin’s campus.

“[The eating disorder] is just this whole other voice overriding my brain, which I’m certain a lot of people on this campus can relate to. I think we are a very anxious, type-A campus. And there are these ‘What if?’ thoughts like ‘What if there’s not enough time? What if I’m not good enough?’” Conroy said.

Morris also sees the harmful effects of the stressful campus environment.

“The same part of my personality that drove my eating disorder I see reflected in a lot of Bowdoin students, which is just this compulsive need to be the best, or feeling like you’re not enough,” said Morris. “We’re just sort of driven to want to achieve the best to a compulsive extent, I think that sometimes gets situated around food.”

In the Orient’s Health and Diet Survey, 38 percent of students indicated they were worried about a friend’s eating habits. That number skewed heavily toward female students expressing concern.

A female sophomore student who has witnessed many friends suffer from and receive treatment for eating disorders expressed great concern about worrisome eating habits at Bowdoin that are often developed under the guise of healthy eating.

“Everyone on campus seems to moralize food in a way that I haven’t seen in what I would call otherwise healthy people before,” she said.

She said the prevalence of restricted diets, such as being gluten-free, sugar-free or vegan, is often perceived on campus as a healthier lifestyle.

“But having a blanket policy of no sugar, when it starts leading to that being what you think about more than being healthy… that can be when it goes into the grey area of maybe being a problem.”

•••

The strong presence of varsity student athletes on campus—about 35 percent of the student body— is an aspect that some students interviewed noted as a factor in their own assessment of their body.

“I was talking to my friend about this like two years ago, she was like, ‘It must be really hard to be somebody on this campus who’s not considered fit because so many people prioritize it here,’” said Friesch. “It’s just so ingrained into the culture but nobody ever really talks about it.”

Manlio Calentti ’20 noted how difficult it can be to maintain a good relationship with food and body on campus with such a high percentage of athletes on campus.

“If you see all these athletes walking around, and you are thinking to yourself, ‘Why don’t I look like that? What can I do to fix that?’ You get into this really bad downward spiral,” he said.  Ann Basu

Ann Basu

Calentti was never diagnosed with an eating disorder, but in high school, was aware of his disordered eating thoughts and habits.

“It catapulted up to binge eating after going through an anorexia phase, so I was never really diagnosed with an eating disorder, but I knew wholeheartedly that I was giving characteristics of severely disordered eating, whether it was not eating anything after a double digit run or eating like 2000 calories in one sitting,” said Calentti.

For him, these behaviors were strongly correlated with being on the cross country team and wanting to become a better runner.

“There was this competition factor of wanting to beat this person and go up in a race and cut down my mile time and my 5K time,” said Calentti.

During his senior year of high school, Calentti went through periods where he was running up to 75 miles a week, yet was consuming fewer than 2000 calories a day. Over the period of a few months, Calentti’s weight dropped from 160 pounds to 125.

Nowadays, Calentti has a healthier relationship with food, although some days are harder than others.

“My life is more balanced but there are still some days where things aren’t quite right and I eat too much, or things are kind of bad and I don’t eat anything at all,” said Calentti.

Another sophomore male, who asked to remain anonymous, has struggled with disordered eating behaviors in the past: he lost 90 pounds over 4.5 months through restricting his calories and doing rigorous workouts.

Now on the crew team at Bowdoin, his coaches don’t do anything that actively discourages gaining or losing weight. However, ergometer tests—tests on the rowing machine to determine one’s speed—are weight adjusted and then sent out to the whole team with individuals’ results.

“It’s not like they are actively saying, ‘Lose weight’ or ‘You need to slim down’ but passively, it’s showing everyone how much you weigh,” he said. “If you have any insecurity about your weight or your performance or how well you should be doing, those results are out there. It’s a lot of pressure on a lot of people, especially me.”

“There’s always the idea that you always have to get bigger or stronger or you’ll get cut,” he said.

•••

A student who would like to remain anonymous finds that her race plays a factor in how she understands her eating disorder. Growing up in Durham, Connecticut, she was one of the only Asian girls at her school and started to internalize how her male friends would talk about girls’ bodies.

“I had the exact relapse of that when I first entered my first year of college in the dorms when guys would go on girl’s Facebooks and say, ‘Oh, she’s hot,’” the student said. “I would start to see a pattern amongst who these girls were, and the light that was going off in my head was, ‘Oh, I feel like I’m not as skinny as them.’”

Although the student struggled with disordered thoughts and behaviors, such as restricting herself and consistently weighing herself, she had difficulty admitting to herself she had an eating disorder until last year, when she went to therapy specifically for her eating disorder.

“I didn’t even admit to myself that I had one until someone had defined it for me, until a therapist defined it for me because I kept convincing myself that I wasn’t skinny enough to have one,” the student said.

She managed her eating disorder in high school, but coming to Bowdoin made it worse, largely due the emotional challenges that come along with being in a new environment and the consistent need to be social.

For students with an eating disorder, the public nature of dining hall meal and the social nature of “getting a meal” can be difficult to navigate.

“In college, I had more restrictive behaviors and more purging because it was so hard to not eat in front in people because people would say something in the dining hall,” she added.

Friesch, too, has found the dining hall to be a place of pressure, constantly finding herself comparing her own meals to those of her friends.

In the Orient’s Health and Diet Survey, 60 percent of students indicated that they paid attention to the eating habits of their peers, and 88 percent of students said they ate differently when at home.

“The hardest part for me about an eating disorder, at least the saddest realization I came to, was all the memories that I missed out on and all the people I never got back to about getting a meal with because of my fear and relationship with food,” the student said.

For Retana, however, having the dining hall helps her to navigate her relationship with food.

“The times where I feel like I’m doing my best to nourish my body and getting the food I need and the amounts I need is when I’ve gone to the dining hall with a friend. I’m grateful for that,” said Retana.

Hart sees dining hall behaviors as potentially harmful, especially in regards to foods that are categorized as healthy and unhealthy.

“There’s a lot of judgement about healthy eating now, but it’s also morphing into this, judging food behaviors versus what’s healthy eating,” said Hart. “I always like to think about that—‘What’s healthy eating?’ Flexible, not judging, letting your body determine what your body wants to eat rather than reading labels.”

This fall, the student who wishes to remain anonymous began seeing a therapist at Bowdoin, but didn’t feel like she was getting enough support and wanted someone who understood the rhetoric and specificities of eating disorders.

Seeing Hart allowed her to find the support she needed, especially due to the physical component to eating disorders.

“She tells me exactly what time to eat or else I relapse, and that’s the kind of structure that I think people who specialize in that field can provide, because there is a lot more of a physical component,” said the student.

Hart thinks that one of the biggest misconceptions about eating disorders is the idea that one must have an extreme one in order to get help, rather than thinking that one can simply have mild disordered eating thoughts.

“So much of the disordered eating is culturally approved. Like it’s OK to calorie count or get uber restrictive with your eating because it’s so ‘healthy’ for you to eat that way,” said Hart.

•••

These days, Conroy would say that she hasn’t recovered, but is on her way.

“Even half a year ago, my whole life was very much ruled by food. Now, my whole life is ruled by recognizing that and then coming up with ways to cope. Realizing that it’s not the food, it’s about what’s really making me anxious, and how can I cope with that instead,” said Conroy. “So I still think about it a lot, but in very different ways now.”

Right now, Morris considers herself the most recovered she has ever been, but understands she has to be careful. She sees a therapist, psychiatrist and dietician off campus to help support her recovery.

“The thing about eating disorders, it’s a lot like alcoholism, like I can never skip a meal because I will click right back into restrictive eating habits, the same way that an alcoholic can’t take a shot of alcohol,” said Morris.

Morris finds the lack of dialogue surrounding eating disorders concerning, yet sees a trend in discussing food and diets.

“I feel like all of our dialogue about food is just so disordered as a society, as a Bowdoin community, that if we started to facilitate more healthy conversations around food that aren’t about food, we’d get back to this place where food is something to be enjoyed. It’s something that nourishes your body,” said Morris.

Sarah Drumm contributed to this report.

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy:

- No hate speech, profanity, disrespectful or threatening comments.

- No personal attacks on reporters.

- Comments must be under 200 words.

- You are strongly encouraged to use a real name or identifier ("Class of '92").

- Any comments made with an email address that does not belong to you will get removed.

You all are so brave for fighting about this and speaking out! Kudos to you all and best of luck in your recovery. I struggled between relapse and recovery for all four years at Bowdoin and am glad the counseling center FINALLY brought Hart in.