A good guy with a gun

November 10, 2017

This

piece represents the opinion of the author

.

This

piece represents the opinion of the author

.

Molly Kennedy

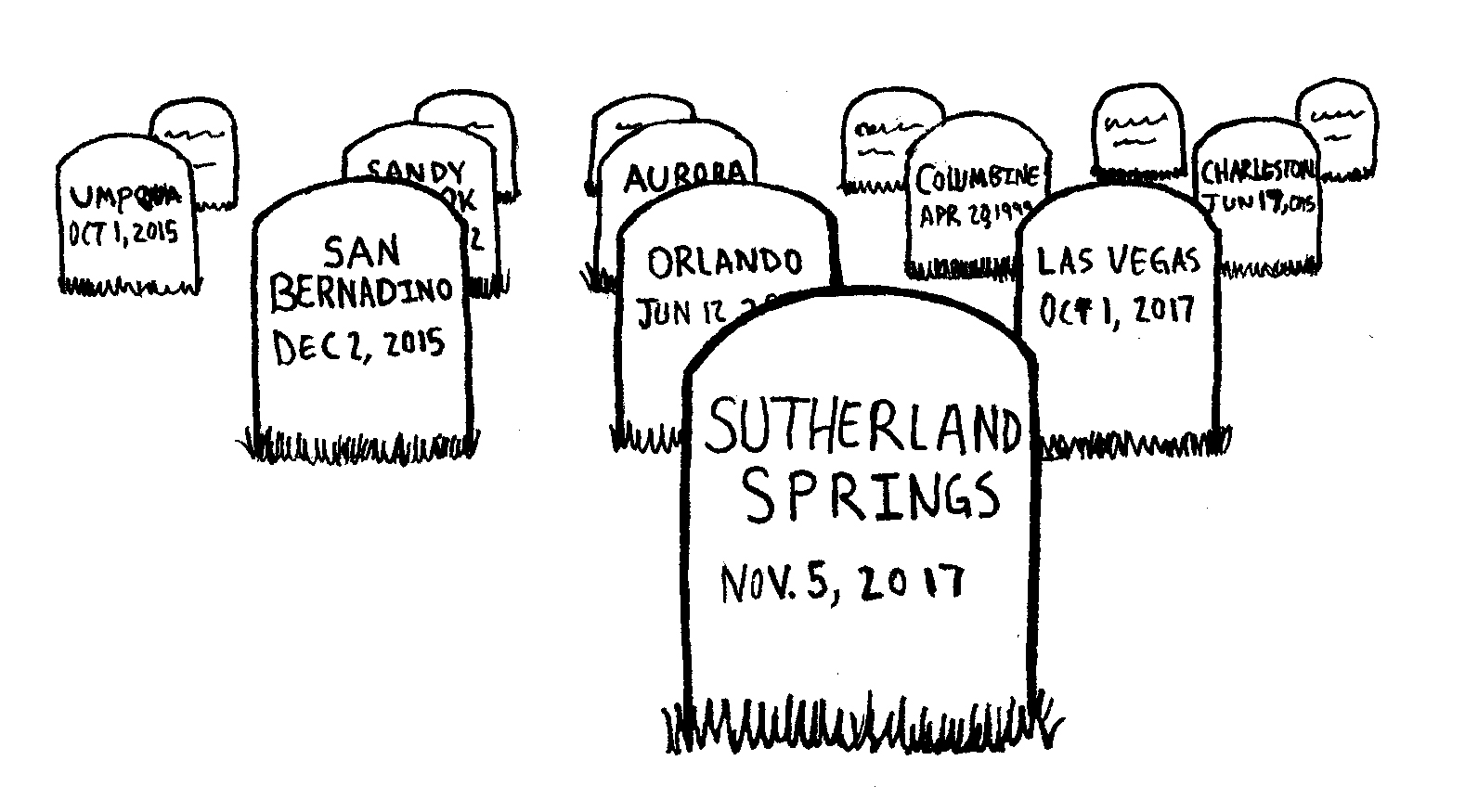

Molly KennedyIf a good guy with a gun exists, it would be inside a church in Texas. I have not lived a life punctuated by the immediate and personal threat of gun violence, nor of violence in general. My family lives five miles over the city line and a world away from Baltimore. The death toll in Baltimore, while achingly high at the end of every year, mounts in intervals of one or a few at a time, the everyday grind of a city whose government has yet to learn how to legislate with human dignity in mind. How easy it is to forget these numbers when faced with the generative fact of my generation: killing and despair on an impossible scale on a clear September day. We’ve never been disproved; calamity and evil eats up beauty predictably. I learned about Tom Petty’s death and the shooting in Las Vegas nearly simultaneously, and then I was ashamed that I cried at the former and just shook my head at the latter. I accepted 58 deaths, and hundreds more injuries, with the cool calm of a child raised in the tailwinds of 9/11, and Virginia Tech, and Aurora, and Sandy Hook, and Isla Vista, and San Bernardino, and the Bataclan and Charleston and Nice and Orlando. You remember Isla Vista, I assume? It’s a distinct event in your mind? Or have the past ten years of your life elapsed in a haze of headlines, bold and italicized, with a body count creeping higher, more men with more guns?

I cannot make policy recommendations. I only just learned what a bump-stock is. I’ve never shot a gun. I never want to hold one. The thought of guns sickens me, whatever their usage. They are fundamentally tools of death, in a way that no knife or truck could ever be. Perhaps I’m impossibly removed, culturally, from the part of the world that sees personal liberty and personal gun-ownership as inextricably tied. The right to self-defense, to defense of property, has been asserted as the core of American rights. I doubt it, but maybe the Second Amendment is actually a guarantee of the right to own a semi-automatic weapon. Maybe we should reconsider what our liberty really is, if we can’t imagine it existing without a concurrent right to end another life.

And sure, maybe we can trace all of this existential blankness back to that culture created by the bomb, the idea of unpreventable suffering on a scale much larger than any one human. I would caution, however, against a wholesale carbon copy of a classic critique of modernity: that the loss of religion, along with a whole host of domestic and geo-political factors, has left us all feeling meaningless, and adrift, and too small and disconnected to handle the meaninglessness of our existence. Nuclear-age ennui was just another, if poignant, facet of a century-long loss. This may be true, but it is not the cause of the despair fostered by our current state of generalized slaughter. This is because, of course, the cause of any of these horrors is not beyond human reason. They are, recognizably, individuals, or a group of individuals. It is not simply knowledge of the transitory and fragile nature of our lives in the face of forces we cannot control that has caused this numbness. It has been caused by a never-ending series of all-too-human horrors. Elliot Rodger and Dylann Roof and Adam Lanza show us the immense suffering one individual can cause a whole society, on top of the suffering they inflict directly upon their victims. They force us to come face-to-face with the monstrous capacity of the human soul. And there is only so much of that knowledge that our own souls can take.

In times like these, as I read about Sutherland Springs, I feel like nothing more—or, perhaps, nothing less—than the sum total of fumbling attempts by parents and teachers to teach me both that evil happened, but that humanity survives it. After so many attempts, I find it harder to believe the second proposition.

I’ve started to have nightmares, which shouldn’t surprise me. My conscious self either refuses to or physically cannot think about this parade of unmourned murder in a productive and processing way. The dreams have different narratives, but they share the guns, and throughout all of them, I survive. I don’t know what my sleeping self is trying to tell me. I have no intention to read any tea leaves. I do know that something has become trapped in our national psyche, buried deep down and screaming to be heard, for enough silence between gunshots and news cycles.

I am tired, and I’m tired of being tired. I am tired of flags at half-mast. I am tired of who this endless stream of tragedies has made me. I would like to be compassionate; I would like to feel the pain of others. I worry that I will sit shell-shocked, not just for an evening or a week, but for my whole life. I have faith in the empathy of my generation, that our notoriously liberal and much-maligned political leanings come from a place of sincere fellow-feeling. Where I have lost faith, though, a faith that I may never regain, is in the belief that our generalized knowledge of suffering is equivalent to a sincere and productive reaction to the reality of that human suffering. I think Sandy Hook heralded the end of human empathy. It forced us not to feel.

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy: