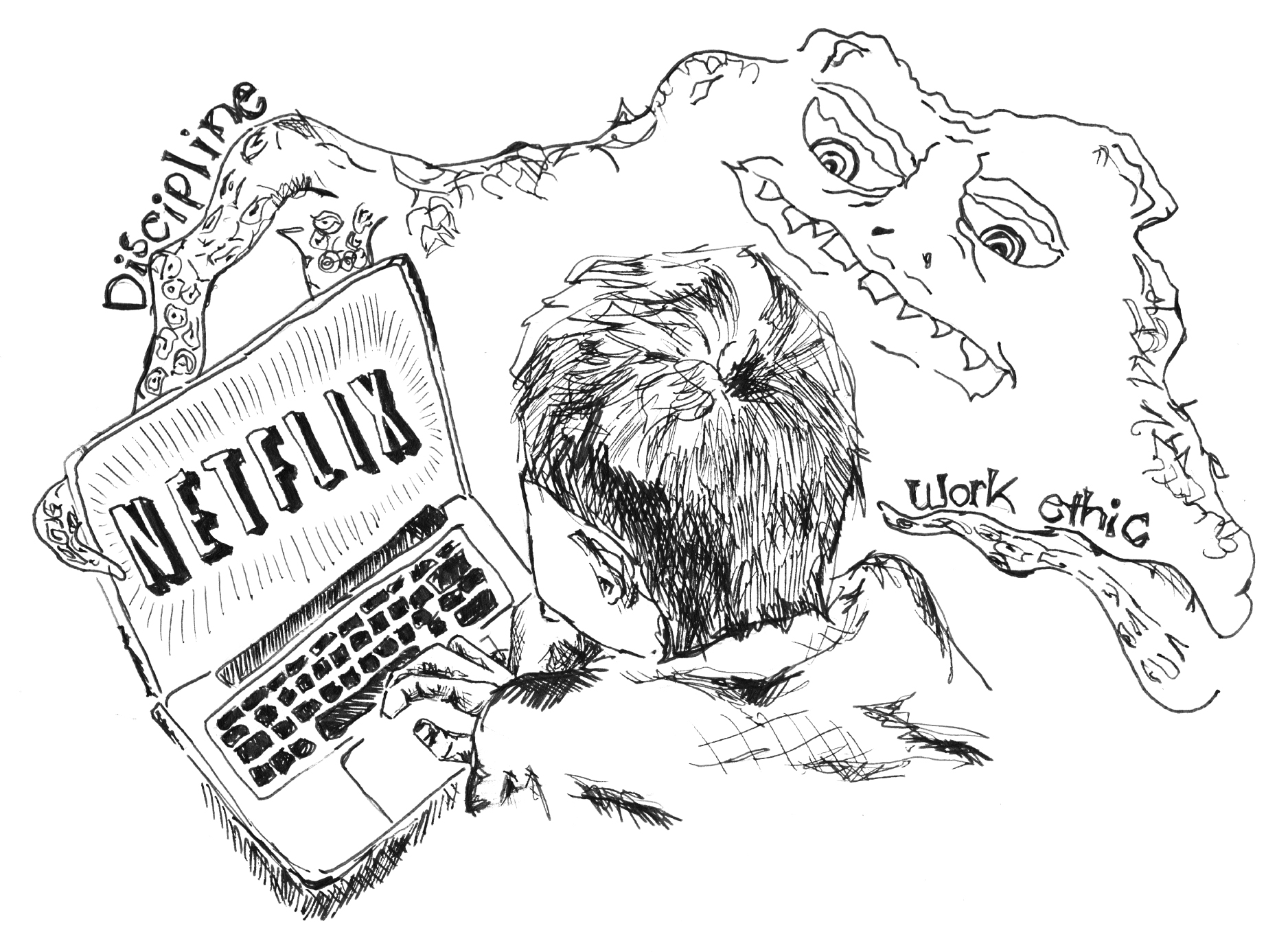

Netflix and still haven’t done my reading: does campus freedom breed poor work habits?

April 21, 2017

This

piece represents the opinion of the author

.

This

piece represents the opinion of the author

.

Phoebe Zipper

Phoebe ZipperNow that spring has arrived in Brunswick, and it is tolerable, even pleasant, to be outdoors for more than a few minutes, I find it increasingly difficult to stay holed up in a library. Whereas the library provides a warm haven from the colder and darker Maine months, now the shining sun makes those same cubicles feel more like cells. Itching to throw a baseball around or lounge on the quad with friends, I relegate school work—against my best intentions—to a place of second priority.

While the non-frigid weather has certainly exacerbated the issue, learning to balance industry and leisure during the first year at college is a perpetual challenge. For those of us entering Bowdoin from non-boarding schools, the sudden blending of school life and home life presents endless opportunities for distraction, diversion and outright sloth. Which isn’t to say that Bowdoin students aren’t busy. To the contrary, many of us have head-spinningly busy schedules.

All the same, I know, and I suspect that many of my peers know, that we are less productive and less focused than we could be. We spend too much time chatting in Smith, too much time scrolling on our phones, too much time watching Netflix in our beds.

Of course, college ought to consist of more than monkish study. The friends we make and the extracurricular experiences that we share serve as much as a pedagogical purpose as they do a purely practical one. The English word “school,” after all, derives etymologically from the Greek word skhol? , which means, approximately, “leisure.” We call schools “schools” because the type of intellectual discourse and liberal studies that we hope to pursue can only be practiced when students, free from laboring after the bare necessity of survival, have enough leisure time to let their curiosities and intellects wander.

Yet perhaps we have gone too far. Fueled by the disintegration and gradual disappearance of structured curricula (and Bowdoin’s five distribution requirements hardly constitute a structured curriculum), the modern American college has wholeheartedly embraced a culture of autonomy. This culture’s first principle is freedom of choice: choice of classes, of majors, of extracurriculars, of housing options, of dining plans, of study-abroad options, of career paths. Even outside the classroom, the ethos of choice permeates our everyday lives, leaving us free to structure our days as we wish. Aside from showing up to class, our abundant free time falls into our own hands.

And it hasn’t all been for the worse. Nevertheless, we should not forget how much the College has changed from its original conception. In his Inaugural Address, whence we got the famous mantra of the “Common Good,” former President Joseph McKeen wrote this about the purpose of the College: “Attention to order, and the early formation of habits of industry and investigation, are conceived to be objects of vast importance in the education of youth. I may venture to assert, that such habits are of more importance than mere knowledge.” He continues, “It is doubtless a desirable thing to facilitate the acquisition of knowledge; but, in aiming at this, there is a serious danger to be avoided, that of inducing an impatience of application, and an aversion to everything that requires labor … If habits of application be of so much importance, it is desirable, that all concerned in the government and instruction of the college should concur in enforcing subordination, regular conduct, and a diligent improvement of time.”

If you immediately recoil from this suggestion, you might have something in common with the college students of 1804, for McKeen follows up by saying, “The volatility of a youthful mind frequently gives rise to eccentricities, and an impatience of the most wholesome restraint; the mildest government is thought oppressive, and the indulgent parent’s ear is easily opened to the voice of complaint.”

Although a complete return to McKeen’s vision of the College as a disciplinarian would certainly be a mistake—the original Bowdoin curriculum would put even the most disciplined of students to sleep—we should think twice about the real fruits of our culture of autonomy. Are you as industrious as you want to be? Do you take advantage of your unstructured free time? Come registration season, do you really feel liberated scrolling through the thousands of courses on Polaris? As I was informed by posters in the basement of HL during finals, “C’s get degrees!” But should they get praise?

I don’t have an easy answer to this problem. The tension between individual freedom and collective responsibility is deeply rooted in the history of our nation and I have no reason to believe our colleges have escaped untainted. Yet it is precisely because this tension informs both our collegiate and public lives alike that we must pay special attention to it.

Since I lack an answer, I will end with a question. Elsewhere in his address, President McKeen writes, “In the natural world we find, that without culture, weeds outgrow more useful plants, and choke them; and reasoning from analogy will lead us to suppose, that without restraint or discipline, the mind of a youth will resemble the field of the slothful, and the vineyard of the man void of understanding.” What type of fruit are the vineyards of Bowdoin bearing?

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy:

- No hate speech, profanity, disrespectful or threatening comments.

- No personal attacks on reporters.

- Comments must be under 200 words.

- You are strongly encouraged to use a real name or identifier ("Class of '92").

- Any comments made with an email address that does not belong to you will get removed.

As a lifetime learner, ahem; I find the superior quality and interrupted flow of content of NETFLIX a refreshing change from daily readings. You can stop ‘learning’ when you want and return when suitable; you can ‘repeat’ a lesson; and you can use it as sounding board for what you’ve learned.

History is really made by ‘characters’ whose persona supersedes the policies they advocate. Reading Churchill is never as engaging as being in a room with him; and it’s something you don’t get by listening to scripted sound bites that are ever so politically correct.