Acknowledging the presence of transphobia

April 13, 2017

This

piece represents the opinion of the author

.

This

piece represents the opinion of the author

.

Phoebe Zipper

Phoebe ZipperTwo weeks ago—on Transgender Day of Visibility, as it so happened—our community was made aware, through an Orient article and editorial, of the incidents that have occurred in some men’s bathrooms on campus in response to the Free Flow initiative’s placement of menstrual products in bathrooms for all genders. On that day and in the days that followed, I was approached by many people, trans and cisgender, friends and acquaintances, who wanted to know my reaction to these transphobic incidents—and to share their own. One reaction that I witnessed extremely frequently, mainly from cisgender and especially heterosexual people, was surprise. “How could this happen at Bowdoin?” was a common refrain. “I had no idea there were actually people here who thought like this!”

I’m sure that all of these people had the best of intentions in making these statements, and it certainly helped me feel a little bit better, in some strange way, to know that trans and non-binary people at Bowdoin were not the only ones who were outraged. However, this kind of surprise reflects a serious lack of awareness that is all too prevalent within our campus community. The fact of the matter is that transphobia does exist at Bowdoin, and even though it goes unnoticed by the majority of people here that doesn’t make it any less salient, and that doesn’t mean it hurts us—the trans community—any less.

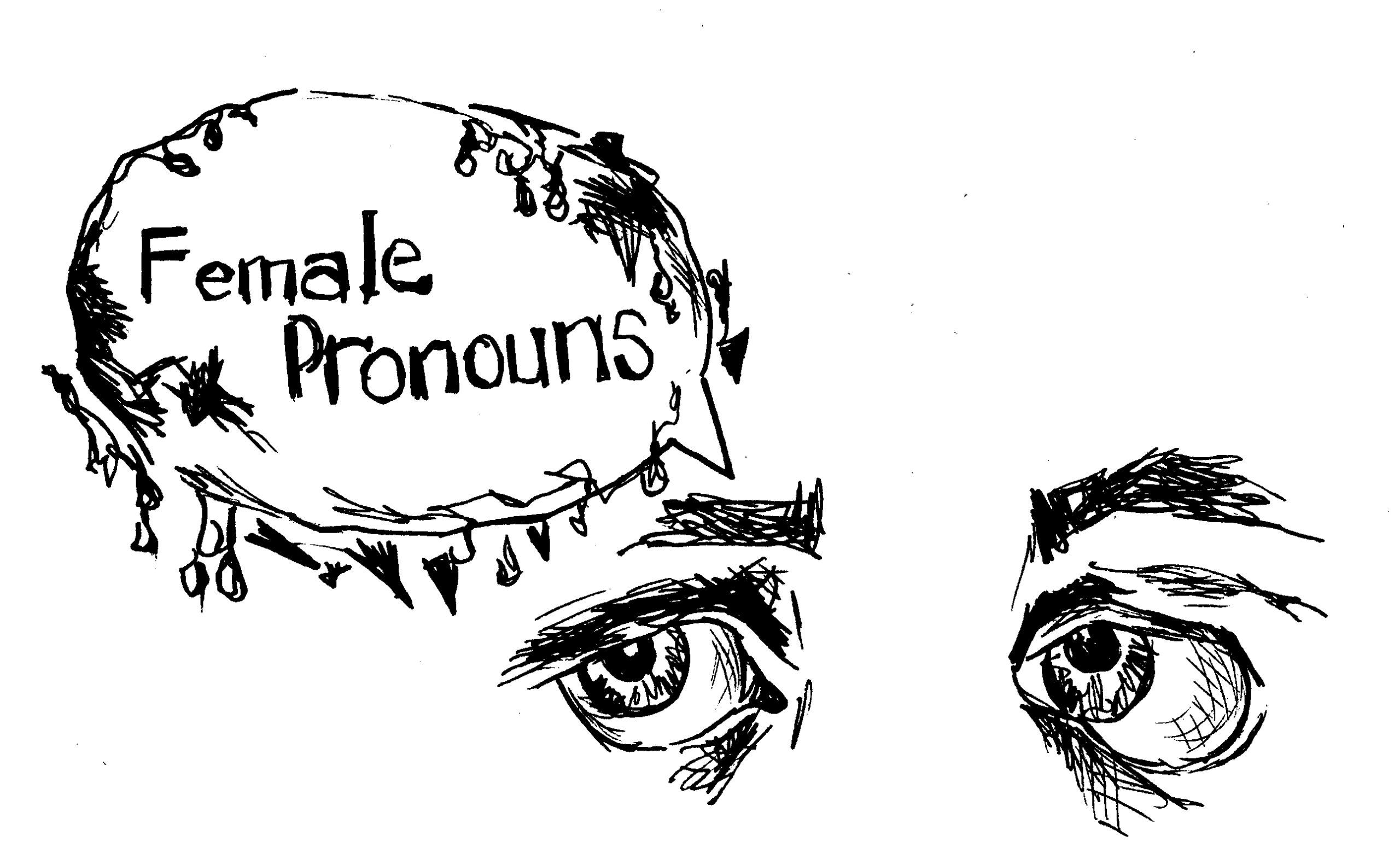

I still feel a paralyzing coldness wash over my body when I remember how quickly my initial excitement was twisted into dread, how it took less than one week for the phrase, “say your name and pronouns” to reveal its true colors and do its damage. What good does it do to have cisgender and trans students alike introduce themselves with their so-called “preferred pronouns” (as if having my gender identity respected by others is merely a preference), if doing so ends up othering us rather than normalizing us? When cis students use the phrase “female pronouns” or “male pronouns,” rather than spelling them out the way we have to, how can they claim to be deconstructing assumptions about the perceived connection between bodies and gender identity? When cis students mock the exercise entirely, how can they claim to be accomplishing anything other than forcing us further into the closet? When cis students refuse to make even a minimal effort to actually use the pronouns that we introduced ourselves with, how can they claim to be listening? How can they claim to be caring about anyone other than themselves?

Surely I do not need to explain why many of the more publicized transphobic incidents that have happened at Bowdoin this year are problematic. Bowdoin’s trans community and our allies have already dedicated our time and energy towards trying to teach others what several incidents—from the proposed “gender bender” party last semester to the incidents in the men’s bathrooms last week—were really about. However, by highlighting the problems on Bowdoin’s campus, I am not intending to claim that they stem from some sort of flaw that is unique to our student body. Rather, they are a reflection of flaws inherent in our society and in our world—a world where trans people, especially trans women of color, are murdered at an alarming rate, a world where 40 percent of trans people have attempted or committed suicide (from transphobia, from rejection by friends and family, from loss of homes and communities, not necessarily from some problem with who we are as people) and a world where our human rights are a “controversial” political topic that is constantly up for debate.

If you care about us, take the time to listen, but it doesn’t stop there. Listening to the pronouns we tell you we “prefer” is not enough if you don’t hold yourself and others accountable for using them. Listening to our perspectives on what is transphobic, what is hateful and what is offensive is not enough if you don’t make a conscious effort to change those behaviors in yourself and to call them out in others. Listening to our explanations of terminology and experiences is not enough if you only rely on us to educate you ourselves and don’t dedicate the fraction of a second it takes to Google something on your own. So do more than just listen: act. Use our pronouns, examine your own unconscious biases, educate yourselves and stand up for us and our rights on both small and larger scales. Be an active ally. Show us that you care.

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy:

- No hate speech, profanity, disrespectful or threatening comments.

- No personal attacks on reporters.

- Comments must be under 200 words.

- You are strongly encouraged to use a real name or identifier ("Class of '92").

- Any comments made with an email address that does not belong to you will get removed.

That’s a good point about the term “preferred pronoun.” Since the pronouns in question are, obviously, personal pronouns, then the words selected are done so not because they are “preferred” but because they reflect who one is (assuming one’s gender identity is a true identity, not not merely a posture).

“Proper pronouns” seems like an obvious substitute, and doesn’t seem like it would be that difficult to popularize.

The demonization of cisgender people by transgender individuals and their allies inhibits the impact your op-ed has and prevents the allyship you seek from being fostered. Two weeks ago, in response to the “Leave Tampons Alone” editorial, a Bowdoin senior wrote on Facebook that “cisgender men are fragile and I hate them.” That one sentence and the vitriol its author feels alienates at least 50%, if not almost all, potential allies to your cause. Shortsighted anger, negatively stereotyping cisgender individuals, and treating them as if they are personally responsible for all transphobic incidents only creates animosity and division.

Your op-ed fails to capture this. I think the transgender community and their allies have some self-reflection to do.

You catch more flies with honey than vinegar.