Insidious threat of climate change demands urgent attention

April 7, 2017

This

piece represents the opinion of the author

.

This

piece represents the opinion of the author

.

By now, sentences like “Our planet and human civilization teeters precariously on the edge of an unfathomable ecological abyss” are banal and, at worst, elicit an ironic smile. We have good reason to believe that climate change might destroy the foundations of our political and economic systems in a matter of decades, but for some reason it doesn’t feel urgent. The threat of climate change is one of those things we are aware of and talk about freely but don’t really understand. It’s all over classrooms but a safe distance from most of our lives.

Climate change is a much more insidious threat than any kind of enemy or opponent we’ve encountered before, partly because it doesn’t work to think of it as an enemy or opponent. It is an abstract, slow, diffuse danger that is hard to hit with the typical problem-solving weapons. America, good at repelling external threats in many ways, has never been good at addressing threats from within or processing its own internal contradictions. Climate change, which has the appearance of an enemy from abroad violently storms onto our shores, is an internal threat—a product of, and a catalyst for, ongoing violence to ourselves.

The name we give the problem is somewhat deceiving. We’re not really threatened by the climate or carbon; the “enemy” is a way of thinking—a set of powerful ideas—which we cannot separate from the institutions and rituals that distribute them.

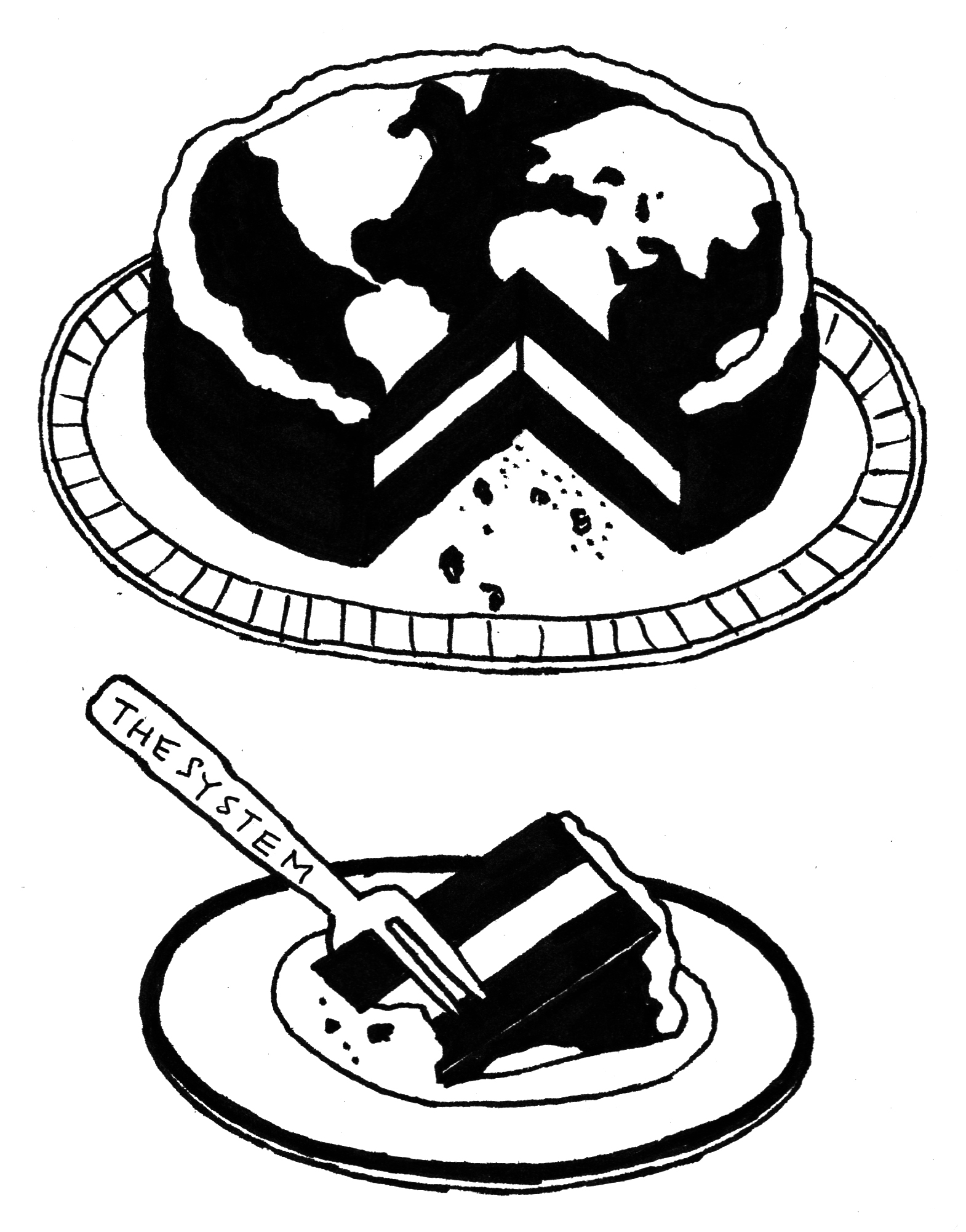

At its core, it is an economic and social problem with deeper, sturdier roots than a few shoddy regulations and energy policies. It is the latest expression of an old disease that has already killed countless people, handicapped whole populations and condemned even more to lives of meaningless struggle. It is the outcome of fatal kinks in our guiding institutions and their ideas, marketed everywhere from governments to churches. I try to avoid empty-sounding claims that demonize capitalism, but there is no doubt that our economic system and the “culture” it enlists have allowed for, if not encouraged, incalculable damages and desecrated modern life. No economic system is evil, but some are especially dangerous in the hands of the morally corrupt—and some of them might even encourage corruption.

Only now are some of the wealthiest, most privileged among us realizing that our comfort and prosperity rest upon insecurity, hopelessness and an incomprehensible suffering. But for most, addressing the climate crisis means doing only what we need to preserve our prosperity and comfort (let us eat cake and have it too). Our administration, board, students and the American left (including Hillary Clinton) all espouse this sort of “environmentalism,” which amounts to support for government policies that seek merely to alleviate the symptoms of the crisis. This hollow approach, which does not confront the extreme inequalities that have defined and destabilized our society, might represent someone else’s deliberate attempts to preserve the inequalities they benefit from. Climate change emerges out of system that has effectively enslaved the poor and it promises to punish the poor most severely.

I’m not just a student trashing “the system.” I’m questioning my leaders, whose intentions and behavior have often contradicted their values—who, often in the name of justice or the common good, have reinforced conditions that extract and exploit. Even if it’s not the mark of a good leader, it’s certainly the task of liberal arts students to question the systems we operate in and our own assumptions about it. Regardless of what the Bowdoin community should do to address the problems that attend climate change, it has a deep obligation to recognize them for what they are. It may not be the role of an academic institution to be politically active, but when ideology constricts intellectual engagement, a free and fearless search for truth must be political.

I think I speak for others when I say that I’m angry at dishonest leaders, whose dishonesty with themselves has hurt others; at every establishment politician who thought that the liberal course of the last eight years would be good enough for America (or that Hillary Clinton was good enough); at my parents’ generation, generally, for denying me the sacred opportunity to be a parent; and at the nauseating pretenses of my own generation (which I share), whose irony betrays sincere complacency.

I wear the divestment movement’s orange square not because I support their tactics, but because it reminds me of the fearlessness of a group that puts ideas into action; and it gives me courage.

Ben Bristol is a member of the Class of 2017.

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy: