Boethius: Death row’s first writer

February 19, 2026

Ethan Lam

Ethan LamWe go to the end, today.

Not really, for any Byzantine heads out there, decrying me for propagating the misbegotten idea that somehow Rome ended when the Western half fell. Nonetheless, though, Caesar has long since crossed the Rubicon. The first emperor of the once-Roman Republic is a distant memory, along with a litany of successors—some glorious, most forgettable.

Latin is no longer a living tongue.

The empire, now dismembered and baptized Christian, is ruled from Constantinople, not the Senate. Even if “Rome” exists in name, what it means to be “Roman” has shifted so much that the term has become its own Ship of Theseus.

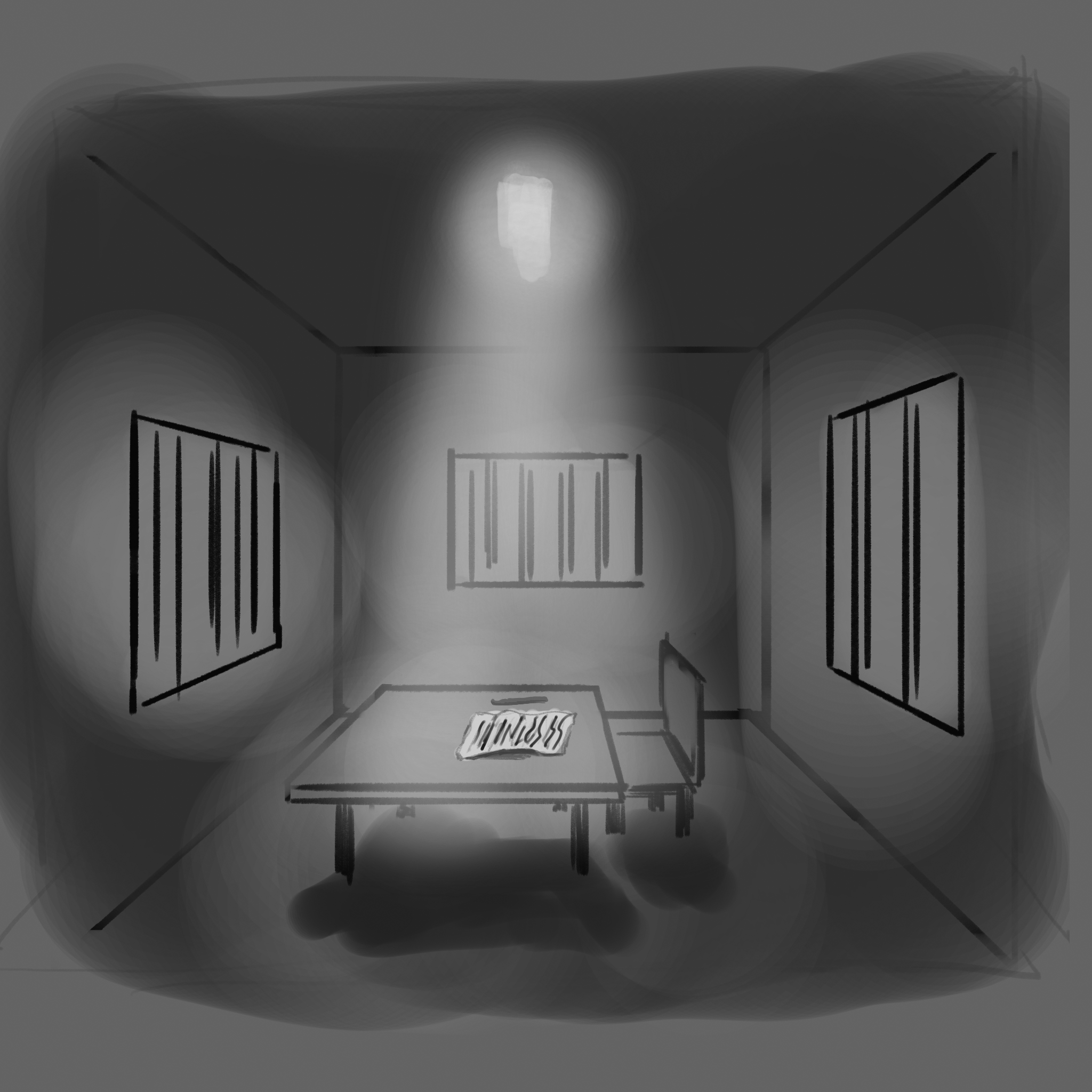

Yet somewhere in the shadow of this crumbling inheritance stands Boethius. Senator, consul, philosopher and, in the end, prisoner. And it’s this Boethius and his work of philosophy, “The Consolation of Philosophy,” written while awaiting execution for treason under the Ostrogothic “Chimera King” Theodoric, that I humbly offer to you.

It is, quite literally, the final gasp of the Roman philosophical tradition—one last dialogue before silence.

I grew up the son of a pastor. For a long time, I believed that meant I understood something about faith. As I grew up, though, and my certainty faded away, I kept looking for that same certainty that comes from growing up with a firm religious identity—and wishing its sudden departure didn’t feel so destabilizing. And when I first read Boethius, I recognized something familiar—not answers, but an ache. A willingness to stay awake inside the unknowing.

Boethius’ work is a grand attempt at making meaning in the most harrowing of times. He is told that he can be executed any day, and every day he must handle that anxiety of knowing it could be his last. He will have no warning, no time to make his peace, just a king whose whim he lives by. During this year on death row, he writes a dialogue between himself and Lady Philosophy, permeated by the very idea that, looking death in the eyes, he must still find meaning and hope.

It is here, my reader, that you likely know what kind of work this Catholic saint must have written. A defense, maybe. A flattery of his captors in an attempt to live another day. Maybe even a tale of classic Christian salvation that, somehow, in these final moments, his faith assures him that even in death, not all is lost.

He does none of these, and it is what he writes about that makes him such a deeply enigmatic and appealing writer. Instead, in a prison cell, with the axe poised above his neck, he turns to reason. Lady Philosophy appears to him, but not to comfort him. She is reason, cold and logical, and she is there to remind him of the truths he once professed and abandoned.

She tells him what he knows but cannot bear to remember: that fortune is fickle, and her wheel always turns. That true happiness does not depend on office, wealth or reputation, but on how we live our lives today. That the apparent success of wicked men is an illusion and that the universe remains governed by a rational, divine order, even when the just suffer.

Boethius does not concede easily. The dialogue that follows is not gentle. It is not simple. It is a slow, painful, often agonizing attempt to think through despair. This is what makes “The Consolation” extraordinary, as an existential act to make meaning more than the dry “philosophical” text that calling it “philosophy” entails.

Here is a man robbed of everything, reasoning himself back into coherence. Reading it, I recognized that same struggle. Not to be saved, but to stay upright.

Boethius does so beautifully. The text moves between prose and poetry, between syllogism and lament. In its form, he captures the subject of representing a life, swinging as we do between confusion and clarity. It is everything; it is sorrow and joy, reason and doubt, beauty and evil.

What is most striking—especially to modern readers—is the absence of overt Christianity. There is no Christ, no resurrection, no divine grace. The God of Boethius is the unmoved mover, the principle of unity and order, not the shepherd of souls. It is a vision shaped by Plato, Aristotle and the Stoics. And yet, it is precisely this pagan framing that gives the work its power. Boethius argues using a timeless appeal that those who are religious individuals or otherwise can turn to as well, creating meaning through his own first consolation, brick by brick.

This makes the book more demanding—and more honest. I’m continually struck by how Boethius does not deny that the innocent suffer or minimize injustice. He insists only that reason can still speak. That if you can remember what is true, you can endure what is unbearable. In a time where reason feels so distant from our every day, where violence waits on all of our doorsteps, that fact gives me comfort. Knowing that thousands of years ago, a man faced with his own uncertainty and violence could find the will to get up every day and still choose meaning.

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy: