Reflecting on the life of President Edwards

December 5, 2025

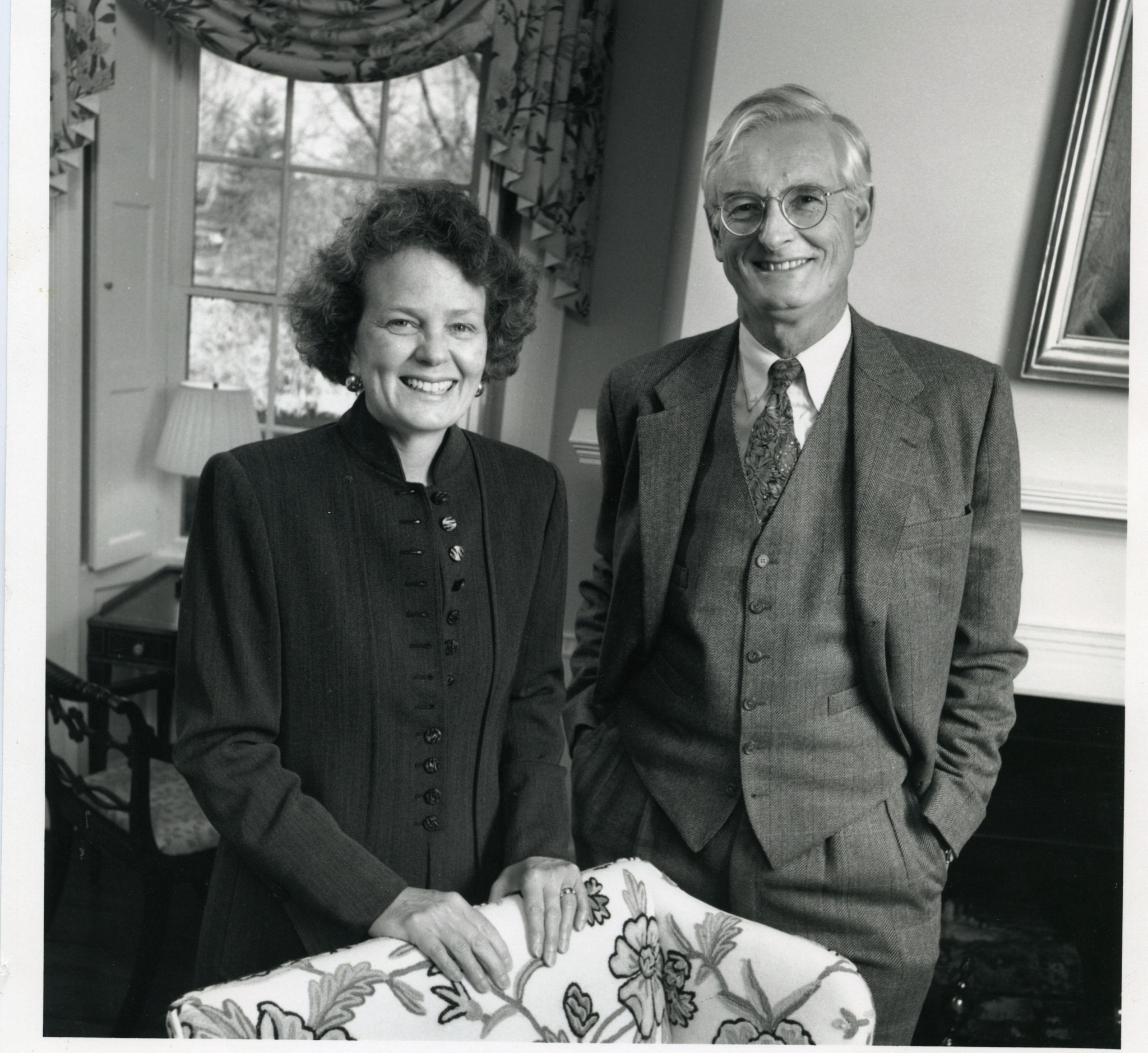

Courtesy of the George J. Mitchell Deparment of Special Collections & Archives

Courtesy of the George J. Mitchell Deparment of Special Collections & ArchivesOn Monday afternoon, President Safa Zaki announced the passing of Bowdoin’s 13th president, Robert Edwards, who served from 1990 to 2001, in an email to the campus community. During his time at Bowdoin, Edwards instituted significant financial and social changes that persist today while leaving lasting memories with those who knew him.

“While Bob had genuine respect for Bowdoin’s history and traditions, he also wanted to make sure that the Bowdoin community never became complacent, that there were so many ways in which Bowdoin could become a stronger institution,” Professor of Government Allen Springer wrote in an email to the Orient.

Edwards and his wife, Blythe Bickel Edwards, were living in Paris when Edwards was presented with the opportunity to become president of the College. When he learned that the College was experiencing financial difficulties, he thought that his experience could be fitting for the job in a place he had always admired.

“I always had loved the idea of Bowdoin because it never seemed to be comparable to any other college in America. It seemed always to be a place that plowed its own furrow. It was a kind of cranky, individualistic place that was in a cranky, individualistic state. And it never seemed to me to be governed by the major trends of society,” Edwards said, reflecting on his time at the College in the February 22, 2000 edition of the Orient.

Edwards saw the removal of fraternities and the creation of the College House system during his tenure as a means of recentering the College’s liberal arts tradition. According to Springer, Edwards’ decision to implement this system was ultimately a success, despite initial difficulties.

“I had spent two years as Dean of Students during the difficult period when Bowdoin was attempting to integrate women into a fraternity system,” Springer said. “[Edwards] … worked hard with the Board of Trustees to take what was at the time a very controversial decision, but one that I believe has made Bowdoin a much better college.”

Craig Bradley, whom Edwards recruited to serve as the dean of student affairs during this transition, cited the importance of Edwards’ leadership in reshaping campus culture to foster a greater sense of inclusion and community through the College House system.

“The important thing to remember is that this sort of transformative institutional change can only happen with an extraordinarily strong, principled, fearless leader. Such leaders are rare. [Edwards] was that leader for Bowdoin,” Bradley wrote in an email to the Orient. “Bowdoin would not be the college you experience today were it not for [Edwards’] leadership in the 1990s: leadership that very, very few other college presidents would have had the courage—and Board support—to exercise.”

Significant capital investments were necessary to achieve this transition, including the building of Thorne Hall to replace dining facilities in the fraternities and new housing with the development of Chamberlain Hall, Osher Hall and West Hall, along with renovations to all of the first-year bricks.

At the same time that Bowdoin was establishing College Houses, Edwards also convinced the College to purchase the Parker Cleaveland House for the College president, where every subsequent president has resided. Edwards defended the decision as an expression of the College as an institution in a 2000 exit interview with former Senior Vice President for Communications and Public Affairs Scott Hood.

“[The Parker Cleveland House] was not our identity; it was the College’s identity,” Edwards said. “And I think students, parents and faculty—and most particularly alumni and trustees—have liked this house as an expression of the College.”

During Edwards’ tenure, the endowment nearly tripled from $150 million to $450 million according to Zaki’s email. In part, this stemmed from Edwards’ interest in becoming a college connected with alumni and institutions far beyond Brunswick while still maintaining relationships within Maine.

“I think that every good institution is rooted in a location more than it knows,” Edwards said in the interview with Hood. “Bowdoin draws its identity from the regiments that went to the Civil War, the nature of the pines, the land upon which we are situated. I think that we would ignore Maine to our peril, but in a way, we’ve got to have it both ways. In other words, in a current world of globalism and national identity, we cannot be seen to be parochial. But if we are not rooted in a place, we become generic. We become plain vanilla; we are homogenized.”

Beyond the endowment, yearly enrollment grew by roughly 200 students during Edwards’ tenure, in concert with larger academic offerings. Edwards expounded on this in another session of the exit interview in 2001.

“The catalogue was too thin. We had six or seven biologists. You can’t have six or seven biologists in a serious life sciences program in the 21st century.… We needed to expand departments. Knowledge was exploding, and we were, by a very long way, the smallest college in our comparison group,” Edwards said. “So, I felt that if we did not swiftly expand and enhance the character of the academic program, we were going to really be at a serious disadvantage.”

Former Senior Vice President for Planning and Development Bill Torrey described Edwards as a hardworking figure who actively sought to recruit students from beyond New England.

“He was a tireless worker. He was a commanding figure, and he had a powerful intellect, and he really wanted excellence on every front,” Torrey said. “He really felt that the student body needed to be represented by students from across the country…. So there was a lot of effort put into the admissions world. He hired Dick Steele, who was the director of undergraduate admissions at Duke University at the time, to become Director of Admissions and really increase the scope of recruitment across the country.”

The Orient reported on Edwards’ intention to resign in the October 8, 1999 issue. In his resignation letter, Edwards said he was proud of the work he had accomplished, focusing especially on the hiring of new faculty during his tenure.

“Institutions are people. We have wonderful older faculty, but they were here when I arrived. On my watch we’ve added to the human capital some wonderful human beings,” Edwards said in the 1999 article.

One of those new faculty was Professor of Cinema Studies Tricia Welsch, who joined the Bowdoin faculty in 1993. According to Welsch, Edwards was warm and welcoming as she entered Bowdoin for the first time.

“As a new faculty member, I was elected to a committee that was—let’s just say—ahead of my skill level,” Welsch wrote in an email to the Orient. “And he helped me understand how to do the work and be part of the conversation. He always treated me like I was someone worth listening to—and that began with my job overview, when I met him for the first time…. [Edwards] made me feel welcome and comfortable.”

According to Professor of Anthropology Susan Kaplan, Edwards was the first president to introduce the process of meeting all tenure-track candidates being interviewed, a practice which at the time was controversial but that Kaplan believes was widely successful.

“This complicated the interview process, and faculty grumbled about it,” Kaplan said. “[But] it was a clear sign that he considered hiring of talented teachers and researchers essential to the functioning of a top-performing institution. On top of that, he wanted to be sure faculty thrived at Bowdoin, so every new tenure-track hire was given a ‘start-up fund.’ This move attracted excellent faculty and provided them the resources to do their research and involve students in it.”

Bradley shared that he is grateful for Edwards’ leadership and mentorship, which he said had a profound impact on his career.

“Personally, having been recruited by Bob and having worked with him until his retirement was one of the most formative experiences of my professional career,” Bradley wrote. “Bob Edwards was an extraordinary mentor, and I am eternally grateful for the gift of his example, something that fundamentally shaped my approach to institutional leadership.”

According to former Dean for Academic Affairs Chuck Beitz, Edwards was a fixture on campus.

“He brought intellectual seriousness and global perspective—characteristics that also won the confidence of alumni and trustees,” Beitz wrote in an email to the Orient. “And he had a great, mischievous sense of humor: He claimed that his favorite film—surprisingly for an educator?—was ‘Ferris Bueller’s Day Off.’”

Former Director of Reunion Giving Pam Torrey reflected on how Edwards made everyone feel that their work at the College was important and part of a greater mission in higher education.

“He really believed that the work that we did in educating young people was of utmost importance, and I always felt so proud to be part of that,” Torrey said. “I was so proud to have worked for him…. I think there were many people who felt like he transformed this College.”

Bradley expressed his sorrow at Edwards’ passing.

“One of Bowdoin’s mightiest and tallest pines has fallen. I am deeply sad to say goodbye to the one we respectfully and affectionately called ‘Big Man,’” Bradley wrote.

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy:

- No hate speech, profanity, disrespectful or threatening comments.

- No personal attacks on reporters.

- Comments must be under 200 words.

- You are strongly encouraged to use a real name or identifier ("Class of '92").

- Any comments made with an email address that does not belong to you will get removed.

Thanks for reporting on this! Unfortunately, the College website did not.