Good students

October 16, 2025

This

piece represents the opinion of the author

.

This

piece represents the opinion of the author

.

Charlotte Ng

Charlotte NgIt’s marked on my report cards for every trimester of elementary school: fantastic student. I had a flawless behavioral record—I always sat still in class, quietly paid attention while the teacher was talking and raised my hand before speaking.

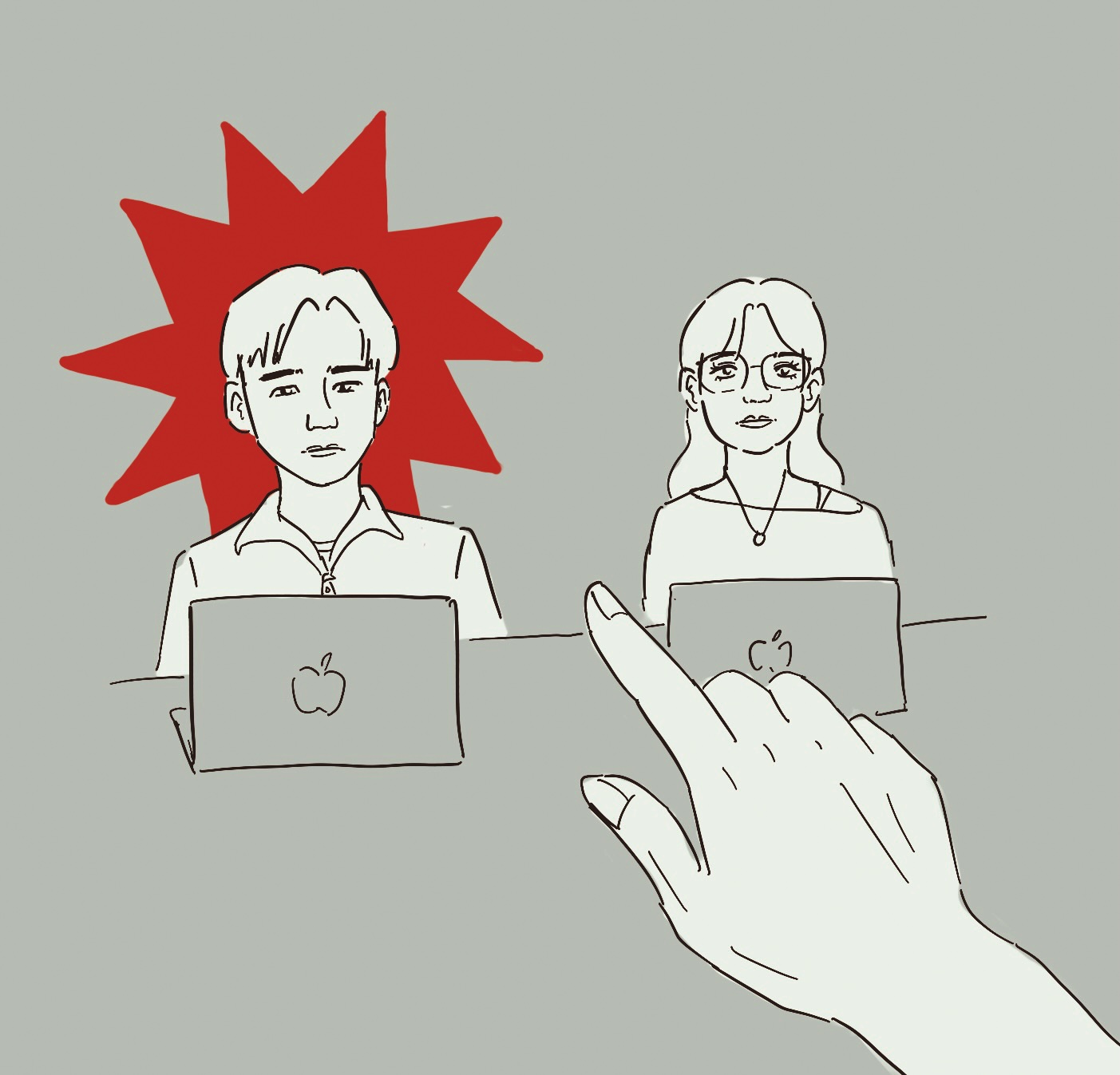

I ran with that positive reinforcement, keeping the knowledge that I “exceeded expectations” as motivation to get those straight A’s through middle and high school. But during senior year, when I looked around my high school calculus classroom, I wondered why the girls in my class worked harder for the same grades as the boys.

Statistically, women outperform men in most aspects of education. Since 1914, girls have slightly but consistently earned higher marks from teachers. Fewer men graduate high school, and men represent only 44 percent of college students. Forty-seven percent of women have college degrees, compared to just 37 percent of men.

This seems like a win for feminism—girls maintaining a majority in a system historically dominated by boys. But when you contextualize these statistics alongside that only 11 percent of S&P 500 CEOs are women, you see an extreme disconnect.

Consider it: A “good student” is responsible. They do the work that is asked of them, are organized, attentive in class, respectful even when bored. They are self-motivated, they meet with teachers after class and take extra credit opportunities to “show they are willing to work for their grades.” It’s all strikingly reminiscent of the ‘ideal’ patriarchal woman.

Researchers at the American Economic Journal in 2019 confirm this: The norms of obedience and hard work that are favored in education are traits more typically exhibited by girls. Corroborating research finds that girls who act into their gender stereotypes attain higher grade point averages (GPAs), while boys who do the same have lower GPAs.

There are no winners. When looking at boys, you see higher dropout rates, a severe variety of mental health challenges and increased social isolation, all because young boys don’t fit the obedient and quiet model of a “good student.” These trends are directly caused by larger patriarchal waves, and the injustice faced by boys in a system that has become increasingly restrictive is a complicated but related issue.

Even though we achieve surface-level success, young, “good” girls also lose. We thrive in school because we behave, follow directions and accept what we’re told. It’s our greatest detriment: We never learn how to succeed without being a mass-produced stereotype.

Psychologist Dr. Lisa Damour explains this. Often, young girls succeed in school by putting in more than enough effort, while young boys put in just enough effort to succeed. This experience helps young boys develop confidence in their abilities while teaching young girls that they’re only successful when they work hard.

In some ways, the way the system fails boys also gives them an advantage. Socialization of young boys in schools rewards patriarchal masculinity and encourages boys to seize authority in the classroom. Young boys are taught to embrace risk taking and ego. This is sharply contrasted with girls, whose stereotypical traits are a result of socialization in childhood and are continually reinforced throughout higher education.

In the words of Jill Filipovic, “Good behavior gives girls an advantage inside the classroom, but it can cost them outside of it later on, especially in high-earning fields.”

Women take fewer risks. In the classroom, it’s the seemingly inconsequential choice between regular and honors calculus, but in the job market it’s asking for a raise or pitching a project idea. Promotions aren’t given to the employees who can best follow instructions but to those who do beyond simply what they’re told to do. Frankly, being ‘good’ and staying inside the lines of what’s demanded isn’t conducive to creativity, a quality that is increasingly important as the job market moves towards artificial intelligence. It costs women promotions.

In addition, it reinforces that a larger volume of work will result in a higher quality result. Girls falsely link high intelligence to ‘good’ studenthood and as a result correlate high intelligence to hard work. And we can see a consequence of this: Female students (especially high-achieving ones) tend to blame their failures on themselves while boys tend to blame external causes like bad luck. It’s a systematic and vicious cycle that erodes girls’s mental health. Success is a result of hard work, and failure means you simply didn’t work hard enough.

And for the good girls that earned all those A’s, their flawless work will only become their greatest flaw.

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy: