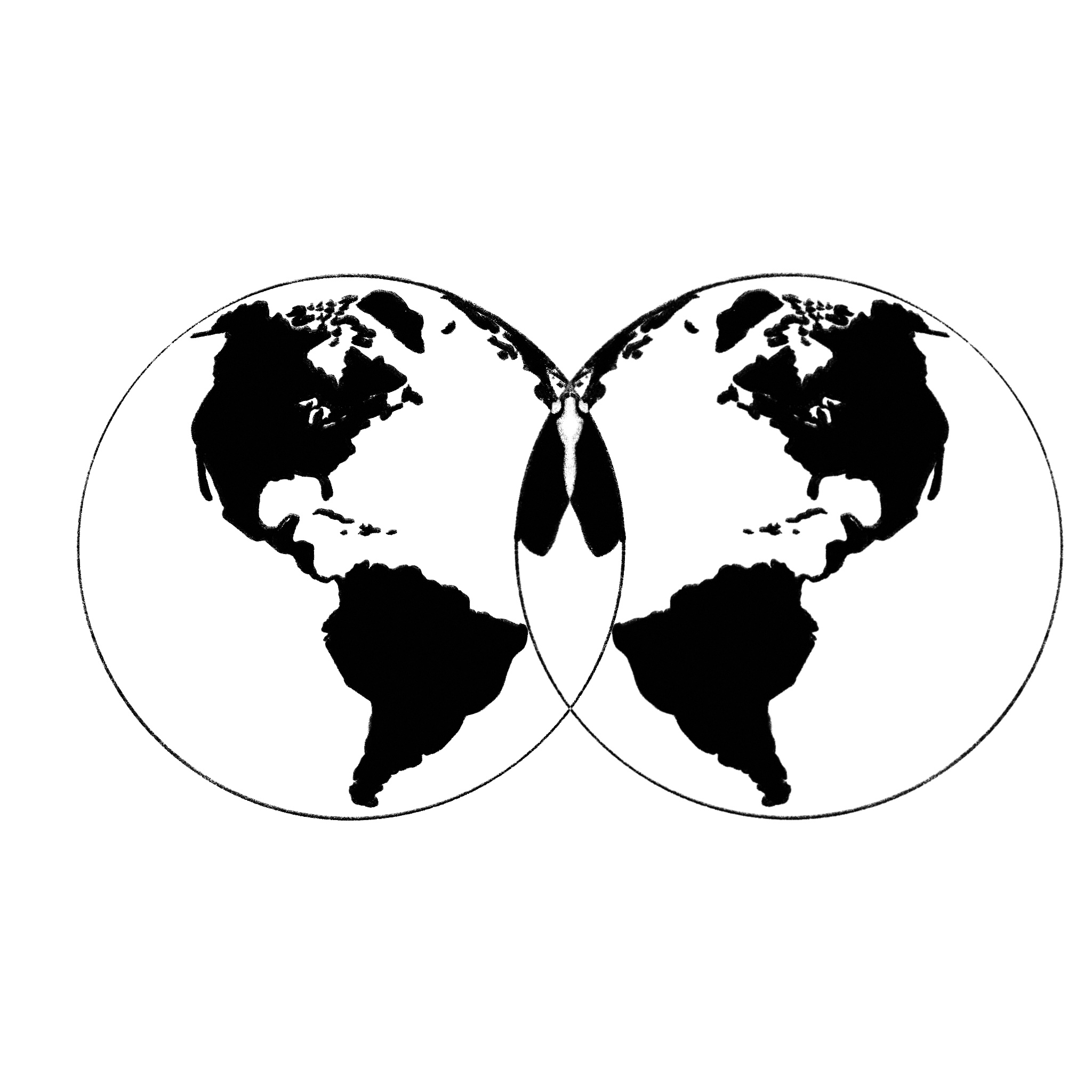

Everything from everywhere all at once: how globalization erodes our bond with nature

May 2, 2025

This

piece represents the opinion of the author

.

This

piece represents the opinion of the author

.

Henry Abbott

Henry AbbottYou squash a honey bee as you sip your morning coffee and look out on the Maine coast. It’s your routine. What you likely fail to consider is that both the species of bee you’ve killed and the coffee on your lips originated in Ethiopia, and the plant-pollinator interaction between their ancestors brought about the first coffee beans humans ever harvested.

Without globalization, we wouldn’t know the first thing about magic mouthfuls of mangos or the waves of weeping willows in the United States. Our globalized society makes a myriad of pleasantries readily accessible to us, but by giving us so much, our globalized economy steals our sense of place and our connection to the natural world with it.

What ties us, or any organism, to our environment? It’s the interactions and the appreciation of these relationships, good and bad, between a being and the various living and nonliving elements that comprise their surroundings: flowers, fruits, flies, winds, wasps and winters. A tree understands its reliance on the underground fungal network for access to nutrients, the sun for energy and the birds and squirrels which spread its seeds and use it as a home. It also understands the risks posed by the taller trees blocking out the sun and the beetles burrowing into its trunk to lay their eggs. Every living thing relies on and plays a part in its local natural cycles. Every living thing besides humans—or so we think.

We used to rely on a deep understanding of the organisms around us to eat. We had to differentiate between berry bushes to forage, recognize deer behavior to hunt and stockpile food for winter. When reliant on our surroundings, we were in touch with nature’s delicate balance and recognized when it was interrupted. Dry summers grew fewer berries, hunting too many deer one year deprived us of venison the next and killing wolves freed deer to eat our crops. We’d know if the bees were dying, that if the soil was sick, our plants wilted, and that if beavers were around, a river swelled.

Today, we’re removed from it all. We exist in sterile, still boxes held at programmed temperatures and filled with manufactured light. We visit the grocery store in the middle of a blizzard to buy fresh fruits, milk, eggs, rotisserie chickens, Cheetos, Diet Coke, prepackaged salads and microwavable burritos. What used to come from all around us now comes from within those four walls. And that’s all that really matters.

Today, we care about the cost of a dozen eggs, the tariffs on aluminum cans and whether mysterious pesticides were used on the far-off fields. The berries we used to pick off a bush we now pick out of plastic buckets on metal shelves in concrete buildings. So, of course, we’ve lost appreciation for the value of an individual plant, its pollinators and its habitat.

Now, try to appreciate the individual organisms and the natural processes that contribute to the creation of something as incomprehensible as a Cheeto or a can of Diet Coke. If you ask me, the ingredients in these foods probably include some sort of corn for Cheetos but could otherwise be anything coming from anywhere. It’s not worth pondering the origins of a Diet Coke’s aspartame, caramel color, potassium benzoate, aluminum (for the can) or even carbonated water when the twelve-pack is conveniently sitting in front of you on the shelf. I’m not asking you to. It would probably take me multiple books to go through all of the natural processes and species that contribute to the creation of a can of Coke and the ways that humans are, locally and globally, interfering with these processes. And that’s the problem.

When what we eat could be anything from anywhere, we lose care for everything, everywhere. In a globalized world, we don’t depend on any unique place or its inhabitants, and by not cherishing any individual part of earth, we devalue it as a whole. As a result, we don’t give economic importance or priority to conserving our natural environments.

Maybe we’ve got it all backwards. Through globalization, we wove an already interconnected world even closer. Uniquely reliant on this elevated integration, we have the most to lose. In the past, the loss of a species could be devastating to a local ecosystem with cascading effects to the surrounding systems that relied on this species and its greater contributions. Now, ecosystems directly provide for humans locally but also globally. Drought in the Midwest dries up the flow of potatoes, soybeans, wheat and corn. Fusarium wilt, a fungal disease in South Asia, stifles the global supply of bananas. Pesticides deplete pollinator populations around the world, preventing the production of produce like blueberries in Maine and apples in Eurasia and South America. Globalization magnifies local ecological disruptions.

Ecosystems around the world are becoming increasingly fragile as we continue to drive species to extinction by clearing habitats for human development and altering environmental processes by contributing to climate change. To prevent future, uncertain fallouts, we need global cooperation that prioritizes funding preemptive conservation of global habitats and species; imagine the ramifications if an entire ecosystem, or even a single species, essential to global, human, food production, collapses.

We need to fight for the conservation of all species and habitats, not just those that seem most at risk. It feels insurmountable, so start simple. Control what you can, be mindful of your local environments and advocate for them. It’s up to all of us, because every place and every species matters. We need to economically emphasize the preservation of the natural world at all scales. If not because regional biodiversity defines our homes, then for the sake of our economy, because 55 percent of global GDP depends on high-functioning, healthy biodiversity. It may no longer be obvious, but our natural worlds still provide us with everything we need, and it’s about time we remember how to treasure them.

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy: