Canonical if you’re cool

March 1, 2024

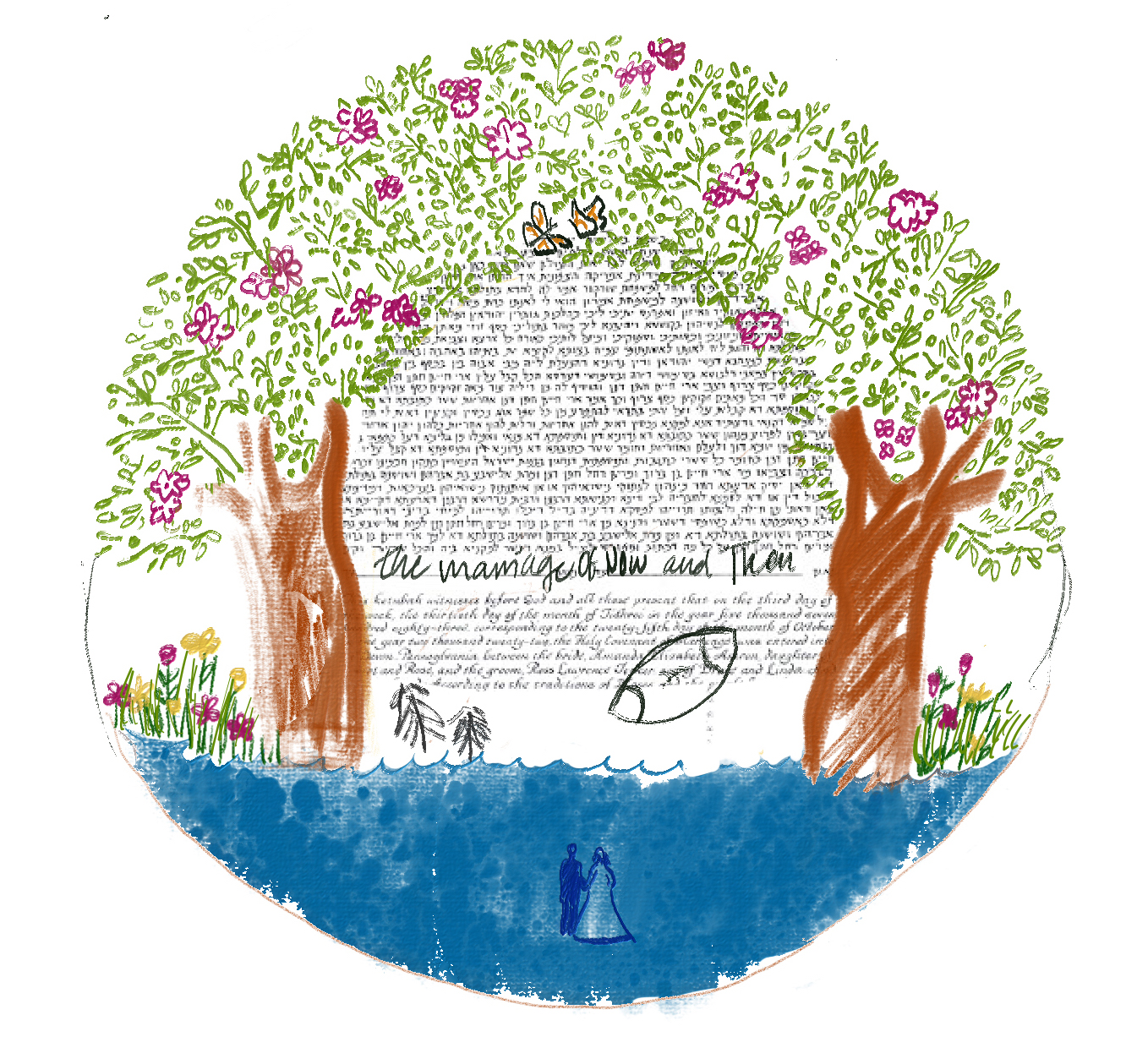

“Perhaps it took the marriage of Now and Then, here in the weeks leading up to football season, to make us realize that in death we are declassified, whether it arrives in European forests that smell like attics or while negotiating a curve by the college library—these words are meant to mark this day on earth.” – David Berman, “Actual Air”

This sentence is set upon dry land: on football fields, the firm dirt of forests and sturdy floors of college libraries. But while this sentence marks time on solid earth, David Berman was infatuated with water.

Berman, the lead songwriter for the ’90s and early 2000s indie band Silver Jews, filled his lyrics, poems, sketches and stories with characters adrift. Silver Jews album titles such as “American Water,” “Lookout Mountain, Lookout Sea” and “The Natural Bridge” suggest a state of being at sea, a liquid metaphor calling forth senses of uncertainty and disorientation reflective of Berman’s struggles with addiction and depression. For Berman, much of life was spent at sea: sometimes flowing passively, other times characterized by a strong current pushing him into the depths.

Yet these particular words, the closing lines to the poem “Tableau through Shattered Monocle,” do not reflect Berman’s liquid infatuation. The poem is firmly grounded in its setting, opening at the home of an English professor and recounting car rides on rigid asphalt and flowers planted in the dirt. This final sentence is particularly grounding. For example, “Negotiating a curve by the college library” suggests a winding road. But as “death” lingers over the sentence, an accident perhaps waits around the bend—and death certainly calls forth the earthly image of dirt, of universal return to the ground. These words are also made solid in their universalization, both in their subject, the broad “us,” and in their moment, the capitalized and thereby personified static time offered by “Now and Then.”

The self-reflexive nature of this sentence leads it further away from the uncertainty of water. The statement that “these words are meant to mark this day on earth” avows that here, Berman is not at sea. Neither is the reader, who is safely returned to the shore that is the conviction of their own existence in reading words which so consciously admit to their presence and purpose. But these closing words also construct an eerily discomforting temporality, as “this day” is constantly changing (I have read this poem on dozens of different days, and you will likely read these words on yet others), and as Berman is no longer marking the earth with his words, having passed away in 2019.

Still, the post-em-dash words that close this sentence are a few of my favorites ever written. They stand as an island of certainty in a storm-whipped sea. Perhaps the inscrutability of their moment in time lends them a particular permanence. I use these words to remind myself of the solid earth I stand upon; I use words, often, to mark my days on earth.

I hesitate somewhat to write about David Berman. I hesitate in part because his poetic sentence deviates from the words I have chosen for this series to date, which have all been lifted from novels and stories. Berman’s status as a songwriter seems to bend this rule further. And yet, his essentially musical identity pulls this sentence ever more to solid land. There is something especially earnest about a singer’s unsung words, which possess honesty and firmness in requiring no explicit melody nor rhythm as backing.

Despite his grounding reassurance, my love for David Berman has taken on a liquid form. I am unable to maintain for more than a number of weeks a singular favorite Silver Jews song. I am wary of admitting even here a current preference, for tomorrow Berman’s rhymes may strike my ears anew, converting my ephemeral taste. I will admit only that “Living Waters” plays as I write. Its opening sentence, in classic Berman fashion, sets the scene immediately at sea, reflecting an ethical ebb and flow. “Now people are good and people are bad, and I’m never sure which one I am,” he writes. Berman adores the turbid, the intangible and the true—they are tools in the construction of a fluid conception of the self. This conception is found in Berman’s poem, too. “That in death we are declassified” suggests that in life we are unknown, uncertain and subject to the changing of the tides.

Novelist Erin Somers reflects in the Paris Review that reading “Actual Air,” the poetry collection in which this sentence lies, is itself an experience of immersion:

“Remember those postadolescent days when a work of art could make your heart thump? Remember the physical symptoms of infatuation? Before your tastes ossified?”

I may someday reflect upon my present postadolescent infatuation with Berman similarly, though I predict that my personal tastes will never quite ossify, but will remain fluid. Perhaps such fluidity is the answer to the temporal puzzle that closes “Tableau Through Shattered Monocle”: Shifting days are marked by shifting words.

And perhaps what Berman suggests in his phrase “the marriage of Now and Then” is that what we experience when we return to sentences held dear is a sense of reassurance in the promise of their constancy. “Actual Air is canonical if you’re cool,” Somers writes in her tribute to Berman. I add here, for the record, that “Actual Air” is canonical if you find yourself at sea. This sentence, read Now or Then, is a return to solid earth.

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy: