A look into alternative Bowdoin party culture

February 16, 2024

Last spring, three seniors threw a series of parties that didn’t look or sound like the typical Bowdoin party. That was the whole point.

The self-described “raves” made Brunswick Apartments pulse with techno music that two of the hosts had come to love while clubbing in Berlin, Germany during their study abroad semesters, a nightlife they loved in part because they didn’t have to drink to enjoy it.

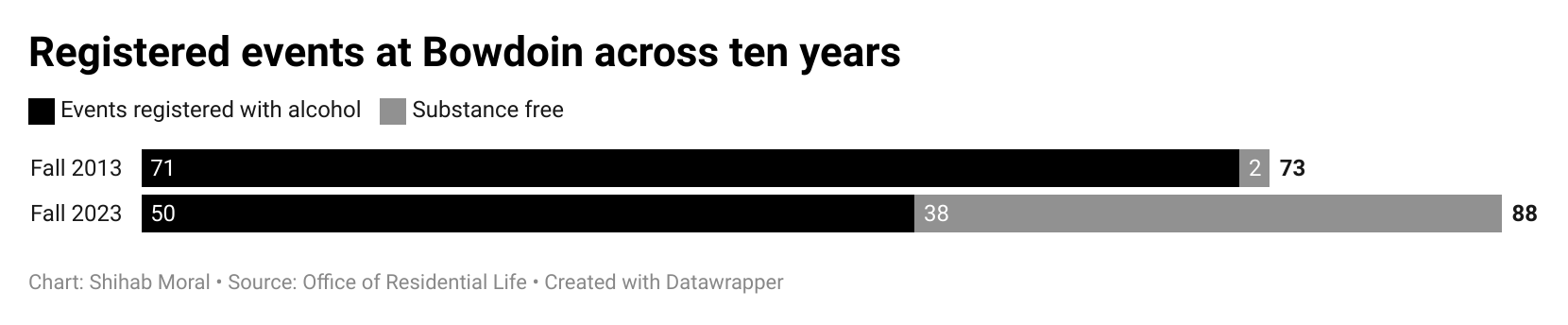

These parties may reflect a change in Bowdoin’s party culture. Data provided by the Office of Residential Life shows that the number of alcohol-registered events has dramatically declined. From 2013 to 2023, registered events with alcohol declined from 71 to 50 while substance-free events increased from 2 to 38 over the same period.

Guests were also invited, though not pressured, to take off their clothing. Host Lily Weafer ’23 said the point was not to make the parties overtly sexual but to make them feel free—of inhibition and judgment, of social anxiety and competition.

Frustrated by many of the parties they attended at Bowdoin, the hosts wanted to create a space where dancing, as opposed to drinking, was the party’s focus. Astrid Braun ’24, a rave attendee, liked the parties for this reason.

“I appreciate people at Bowdoin who put a focus on dancing, because I don’t drink that much, but I love to dance. I’ll stay out until 4 a.m. dancing,” Braun said.

“I … always found that [at Bowdoin parties] people were sort of tense and that everyone was watching each other,” Weafer said. “We wanted our parties to be more of a communal experience rather than a socially competitive vibe.”

Whitney Hogan, the director of Residential Life (ResLife), offered her interpretation of the data.

“I don’t think that you can necessarily extrapolate [alcohol] consumption trends from registration trends,” Hogan said. “But what I do think you can extrapolate is there are more students having events, this past fall or more recently, where alcohol is not the central focus of the event.”

The Berlin-inspired parties (unregistered with ResLife) are an especially vivid example of a subculture of Bowdoin’s social life, far from the dominant party culture established by sports mixers and College Houses. Braun finds quarties—short for queer parties—and events hosted by affinity groups to be inclusive, traditional party alternatives.

“I like quarties,” Braun said. “I’ve been to SASA (South Asian Student Association) parties that have the same vibe. “My roommate is an international student, and she says that she loves the international student parties … because it’s just like, ‘oh, this is our community and we’re just gonna have fun together,’” Braun said.

By agreement with the Orient, the other two hosts asked for anonymity in the online version of this story to avoid being identified by potential employers. This story will use the letters B and E to refer to them.

Yearning for something different

In addition to what she saw as an overemphasis on drinking, Weafer also disliked how hookups seemed to be the center of Bowdoin parties.

“My senior year I was like, I think I’m capable of having more fun than playing beer pong when [I’m] trying to flirt with a bunch of guys on the hockey team or something. I also don’t have anything against that,” Weafer said. “It was just frustrating to see that was the dynamic of every big Bowdoin party.”

The hosts noticed that they were not alone in this feeling. Braun, a member of multiple sports teams, was also frustrated by how sports mixers—parties between two teams, most often a men’s and women’s pairing—perpetuated this culture.

“[In sports groupchats] there are texts about the gender ratio of men to women. Like, ‘oh, we got this other team for the gender ratio,’” Braun said.

With this in mind, the hosts returned from their study abroad semesters motivated to recreate the atmosphere they’d found in Berlin.

“The raves felt like very queer spaces. They had very loud music and a lot of different people feeling very comfortable with themselves and in their bodies and dancing how they wanted and drinking or not drinking and smoking or not smoking,” Weafer said.

Courtesy of hosts

Courtesy of hostsLetting go of inhibitions

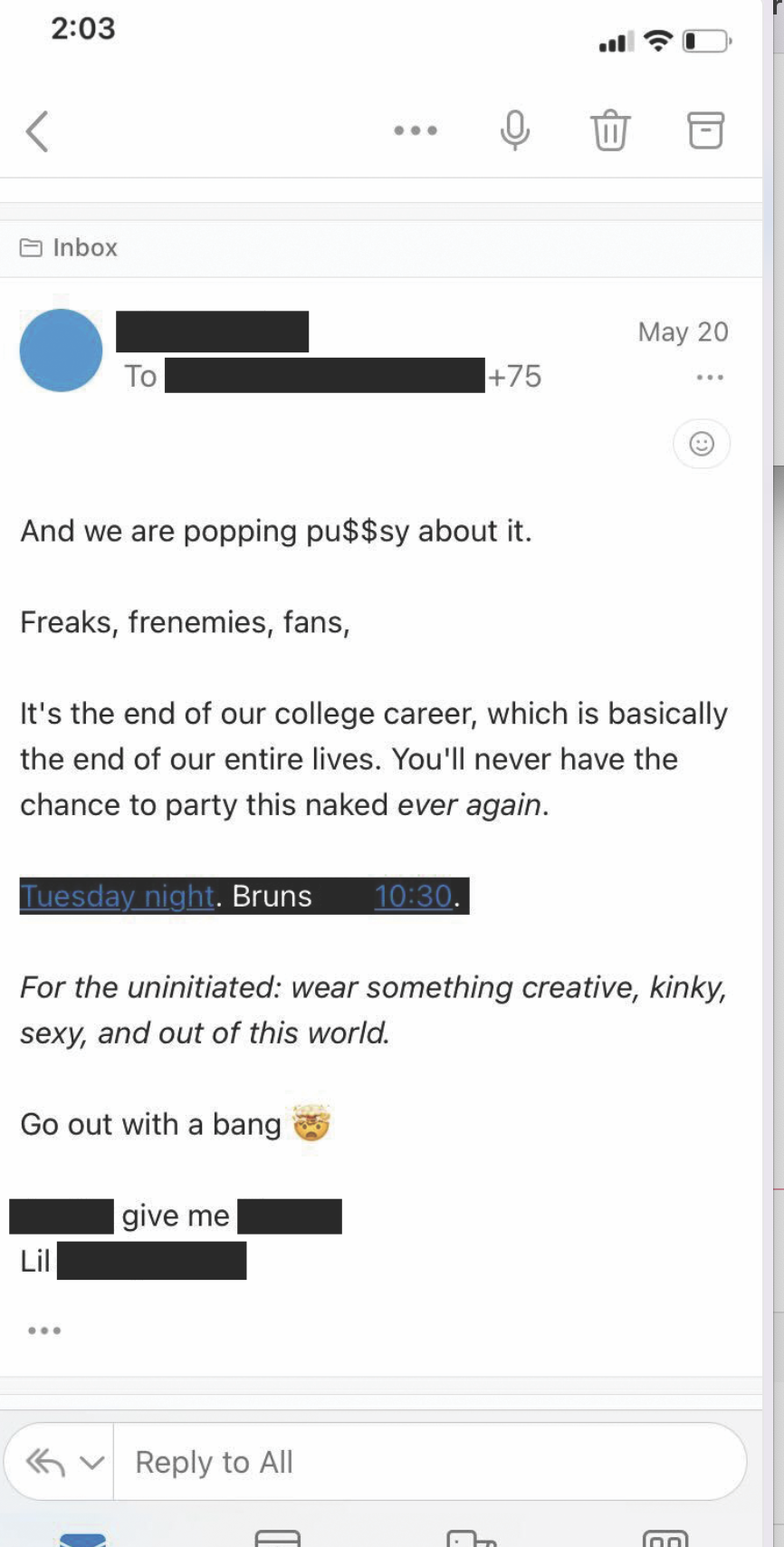

The hosts found it freeing that in Berlin, people wore little clothing at raves. In their invitation emails, they suggested that guests do the same. According to Maria Garcia ’23, who attended all of the raves, attendees were initially hesitant.

“The clothing piece definitely evolved over time because it was just tricky to get people to do that in a comfortable way,” Garcia said. “As the parties went on more people had gotten the memo, which made other people more comfortable that they weren’t the only one not wearing much.”

Weafer said her and the hosts’ embrace of nudity helped others embrace it.

“For the first one, I wore completely ripped jeans and just tape over my nipples. And I think that shocked a lot of people who came in. But our friends were also down with it. So then people were just taking off their shirts,” Weafer said.

Nudity at parties used to be more common. A 2006 article in the Orient described “an annual naked party” that began in 2004. In the past, this tradition was taken to extremes. A 2008 story reported that one man stripped naked at around 10 birthday parties when he was a student.

When asked if these naked parties could create a sense of community on campus as the archives suggest they can, Hogan reflected on how conversations at the College around these issues have changed.

“I think we have entered a place socially—and I think it’s a good place—where people are much more aware of boundaries and people’s varying levels of comfort,” Hogan said. “The ideas around inclusion and our understanding of Title IX, I think, leads people to ask broader questions about nudity and hang out with people in a way that I feel pretty good about, actually.”

Braun, who wore less clothing to the rave than she usually does at parties, said she was slightly nervous about the nudity but felt comfortable once she was there.

“I think I’m lucky and grateful to have a good relationship [with] my body, and so it was enjoyable and interesting and freeing,” Braun said. “I also felt very safe in that environment..”

E said dancing with little clothing felt liberating.

“I grew up feeling really, really ashamed of my body, playing a sport that required wearing a leotard,” E said. “ Being topless at a rave dancing and jumping around is the opposite of that experience and that shame.”

When asked how people whose bodies don’t fit a conventional standard of beauty may have felt at the parties, Weafer said she was uncertain.

“I definitely can’t speak to how they felt because I have no idea. I would say I’m a more ‘straight-sized’ woman. So it’s also, I think, just easier for me to feel like my body belongs in a lot of places, especially at Bowdoin,” Weafer said. “It seemed to me like everyone was comfortable.”

Weafer also acknowledged the risks of sexual misconduct at a party like those she hosted but said that for her, the party felt safe.

“This space was not exempt from the issues we have as a society with people struggling with physical boundaries and emotional boundaries, especially when there’s alcohol involved,” Weafer said. “[But] I definitely wouldn’t say there was more sexual harassment than other parties where there’s less nudity. If anything, it was a slightly more sexually comfortable space for me and my friends.”

The hosts intentionally invited fewer people to minimize the threat of sexual misconduct.

“When you go into a space [with minimal clothing], you want to know most of the people on the invite list, and that’s why we had a smaller invite list,” B said. “I think when you have a naked party, it’s smaller, and therefore everyone knows each other, and so people are less likely to make moves that are unwanted.”

One point of the raves was actually to make it feel less sexually charged than other parties. The techno music they played at the parties helped with this.

“The style of dance for techno is just unsexed…. You can move in any way you want, not specifically in a way that other people are going to find attractive. Sometimes you just flail,” E said.

Braun said the music made people dance less self-consciously, and that she didn’t need to know the lyrics to dance to the music. She only needed to pay attention to the beat.

“There are situations where it takes less mental energy to dance and less confidence or bravery. I think depending on how big the space is, how many people are there, what music’s playing, you feel more or less perceived for how you’re dancing,” Braun said. “I think when it’s a slow Taylor Swift song, no one’s dancing. [With the techno], it flowed a bit more naturally and you were more focused on, ‘Okay, what’s the beat now?’”

Weafer left Bowdoin surprised that she affected Bowdoin’s party culture.

“I think we didn’t know that we as Bowdoin students were capable of making a better space together,” Weafer said. “It did feel actually really special to know you can make what you want happen.”

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy: