Chicago: Davarian Baldwin’s center of Black anti-fascism

February 3, 2023

Emily Campbell

Emily CampbellOn Thursday evening, Trinity College Professor Davarian Baldwin visited Bowdoin to give a lecture titled, “Chicago Could Be the Vienna of American Fascism: How Two Black Graduate Students Transformed Higher Education’s Vision of the American City” in the audience of a crowded Beam Auditorium.

Charles Dorn, professor of social studies and chair of the Department of Education, introduced Baldwin.

Baldwin began the lecture by drawing a connection between the resistance to redlining housing policies in Chicago and the ghettoization of Jewish people in Berlin.

“Chicago’s South Side Black community had been largely hemmed in from all sides through the city’s notorious enforcement of racially restrictive covenants,” Baldwin said. “These [covenants were] legally binding agreements to not rent, lease or sell property to non-whites. In response to this, in the 1937 edition of the Black paper The Chicago Defender, there was an editorial called ‘Building Ghettos.’ That Black journalist and activist [who wrote the editorial was] advancing a unique campaign against these covenants that was specifically Black [and] anti-fascist in nature.”

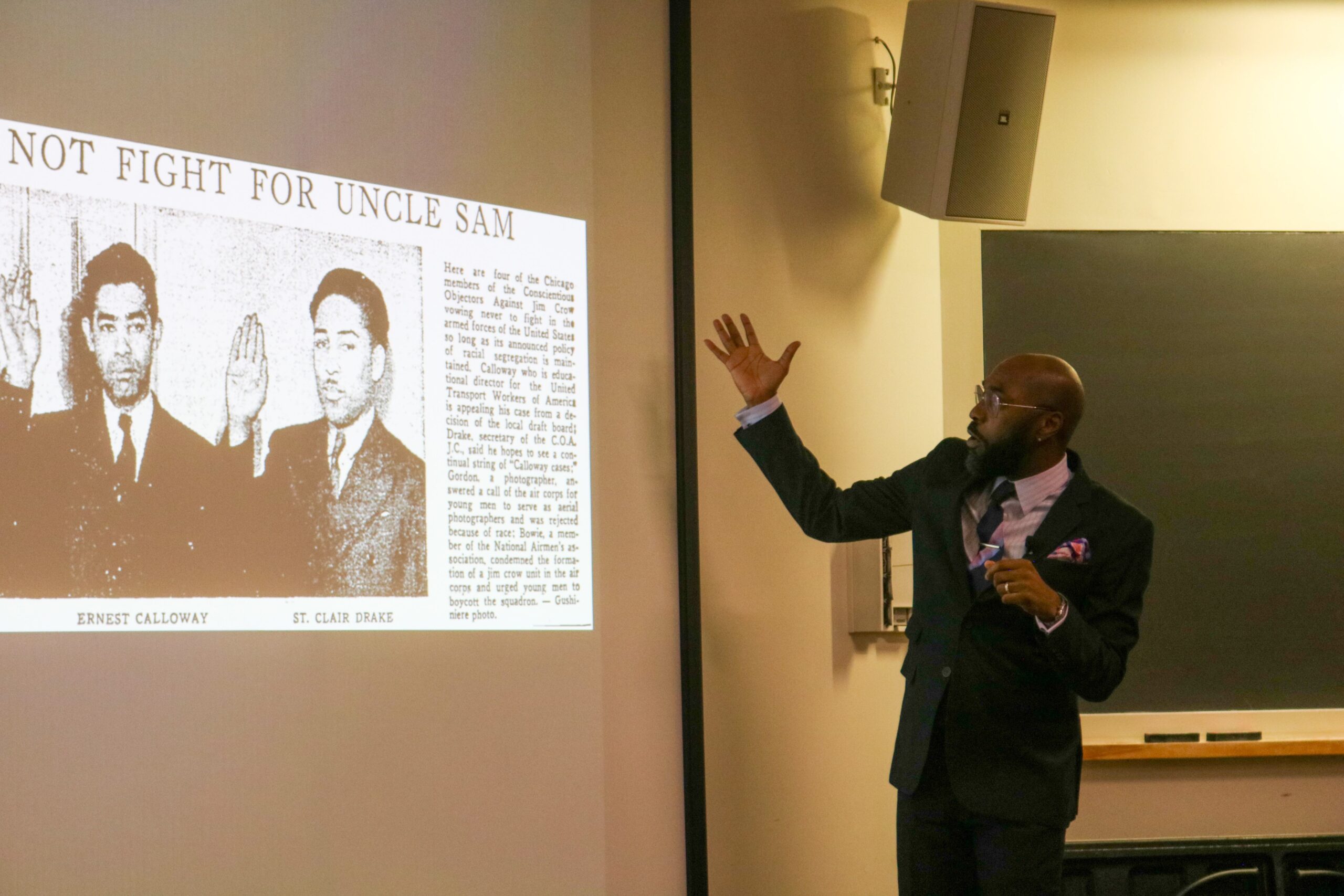

His lecture specifically focused on two University of Chicago sociology graduate students, St. Clair Drake and Horace R. Cayton, Jr.. Their work in the 1920s helped dismantle the idea—which Baldwin said to be rampant in sociology at the time—that racial segregation in cities formed naturally.

“The argument that people naturally move to certain areas, that certain groups inherently bring down property values … [is] the dominant thinking of the day,” Baldwin said. “Then here come these two Black graduate students saying, ‘No, this is a product of structural inequality.’”

Baldwin said the two graduate students combined their work with on-the-ground action in a way that academics tend not to, culminating in their book “Black Metropolis” published in 1945.

“‘Black Metropolis’ directly challenged [St. Clair and Cayton’s] mentor Robert Park and his dominant theory of human ecology that was used for public policy,” Baldwin said. “That was the foundation for redlining. That was the dominant thinking of the day. And here comes these two saying no, the city’s not organized [like that], this is a product of structural inequality [and] intentional oppression. The city isn’t naturally designed by human ecology and is [intentionally] organized in a ghetto-like formation.”

Baldwin argued that this culture of Black anti-fascism helped to bridge the gap between grassroots anti-racist movements and the ‘Ivory Tower’ of higher education.

Yasmine Biyashev ’26, who attended the talk and is from Chicago, said the lecture provided depth to Chicago’s racial history in a way that her secondary school education did not.

“In middle school onwards, they touch upon Chicago history and Chicago racial segregation, but not to this extent and not to an extent that is as honest as I think outside the education system,” Biyashev said.

Baldwin runs the Smart Cities Lab at Trinity, which he said aims to build a mutually beneficial relationship between universities and the cities they inhabit.

“The primary kind of relationship that [one] needs to identify is that whether you’re a public university [or] a private university, [and whether] your prosperity [or] your success is tied to public dollars, whether that be through federal grants through the tax exemption of your land, or through financial aid that comes to the university through individual student,” Baldwin said in an interview with the Orient.

Baldwin’s recent book, “Shadow of the Ivory Tower,” explores the relationship between universities and urban community development, looking into issues of labor, land control, policing and health care in those communities.

Associate Professor of Africana Studies and History and Chair of Department of Africana Studies Brian Purnell was struck by the modern implications of Baldwin’s connection.

“[My biggest takeaway was that] Black Americans had a strong anti-fascist critique that ran through not their understanding of what was necessarily happening in Europe, but through what was happening here,” Purnell said. “And we really need to learn from that history and from them. If we’re going to save our democracy, which is what they were trying to do, [then we have to do] that.”

Purnell was equally impressed by Baldwin’s presence as a speaker.

“It was exciting and it was inspiring both for scholars and students,” Purnell said. “And that’s a very hard level of academic communication to achieve. To be able to speak to specialists and non-specialists at the same time show[ed] Professor Baldwin’s care and investment in ideas for their sake and for their applicability.”

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy: