The Look: The unique religious sci-fi of Dune

November 4, 2022

Kyra Tan

Kyra Tan[This article contains spoilers for the movie Dune]

The sci-fi genre is teeming with worlds of the future marked by technological advancement beyond our wildest dreams. We see how such technology and scientific knowledge influence society’s view of the world and how they affects the ways in which characters interact with each other. While these worlds are commendably rich and vibrant, they have the tendency to conflate scientific advancement with the areligious. “Star Trek,” arguably the most popular sci-fi show of all time, had heavy anti-spiritual undertones that are reflective of the philosophy of show creator Gene Rodenberry, who was a profound and vocal atheist. These future worlds, the authors will argue, have learned so much about the nature of the cosmos that they were compelled to view as foolish any position that professed a world beyond the empirical. Even further, many of these worlds claim that religion and spirituality are wholly impotent forces that push people towards vice rather than virtue, saying that even if we could preserve religion following scientific advancement, we ought not. There is one sci-fi world, however, that bathes itself in spirituality and religiosity and affirms the power these forces have on society even in the face of such vast technological and scientific development: Frank Herbert’s “Dune.”

Dune is a peculiar sci-fi universe, as it is one that lacks many of the standard trappings of the genre. There are little to no robots in Dune and very few AIs, as there was a war against what the citizens of the universe call “thinking machines” many years before the beginning of the book. Moreover, they have an unconventional method of space travel, which involves the ingestion of a substance called spice melange, which allows navigators to divine the path they ought to take through space while moving at warp speed. All of this already sets Dune apart from its contemporaries, and its point on spirituality is equally unique.

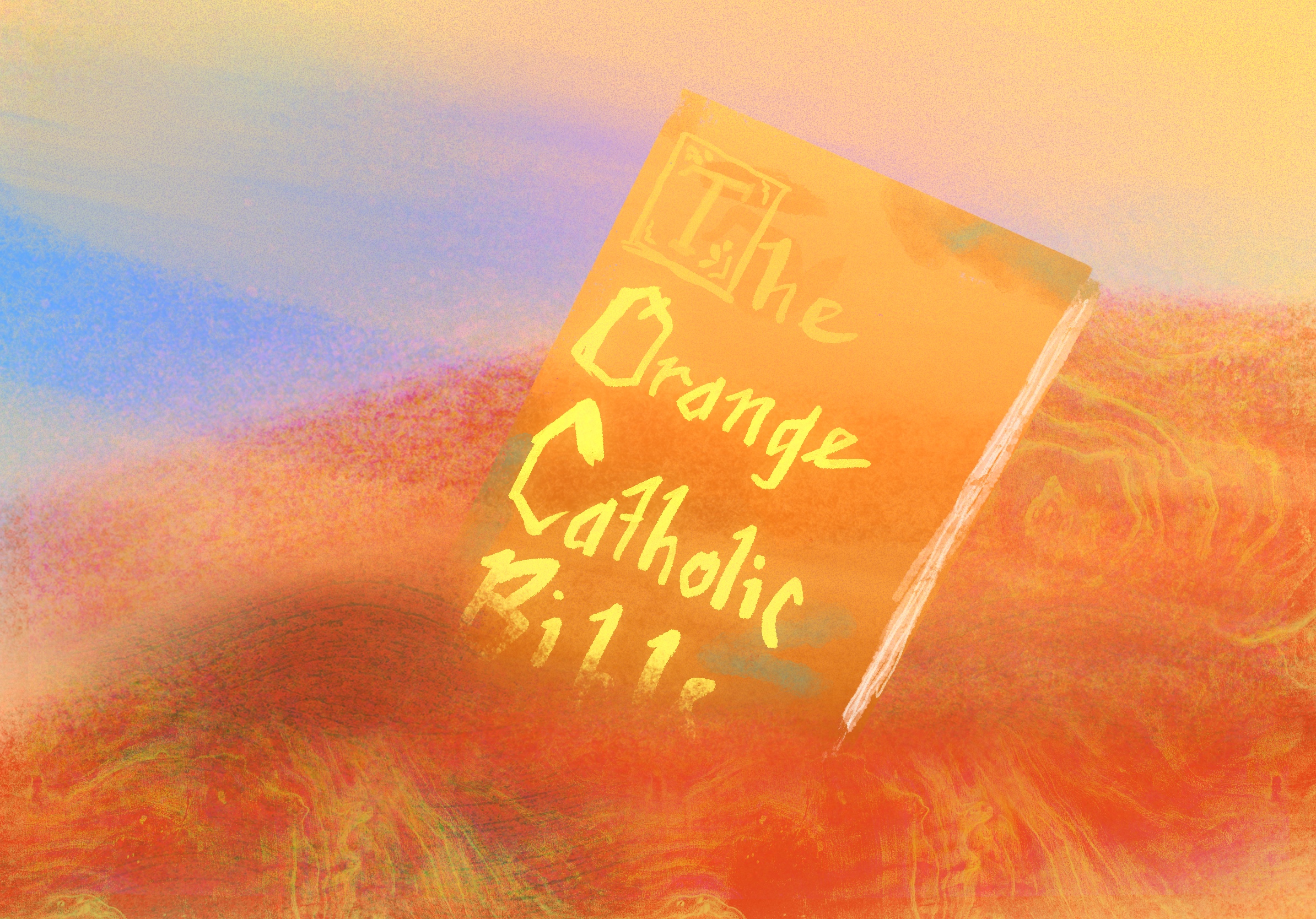

The main political actors of Dune all adhere to an unnamed religion whose holy book is called “The Orange Catholic Bible.” It is made clear throughout Dune that, at some point in the past, all the major religions of Earth united into one. Ever since, the religion of all humans has been an amalgamation of the various faiths we are familiar with in the present day. The Fremen, the inhabitants of the desert planet Arrakis (otherwise known as Dune, hence the book’s title), follow a separate religion that revolves around the great desert worms that create spice melange beneath the sands and the promise of a messiah figure that will lead them to a land filled with water. One of the main conflicts of the book is the struggle of the main characters to understand and accept the beliefs of the Fremen, which they initially view as primitive and foolish but come to accept by the end. Ultimately, it is the beliefs of the Fremen that allow the main character, Paul Atredies, to triumph and fulfill his destiny.

One of the major themes in Dune is the power of religion, whether it is based in truth or not, to mobilize and to inspire people. The main character’s mother, Jessica Atredies, is part of an all-women cult known as the Bene Gesserit and is often heard reciting the mantra, “you mustn’t fear, fear is the mind killer” during many stressful moments in the story. It is the Bene Gesserit, more specifically Jessica, that incite Paul Atredies to live up to the mantle of Kwisatz Haderacht, a prophetic figure who will be the only male to learn the Bene Gresserit art of intense psychological control of oneself. Moreover, the entire second half of the book revolves around the attempt to realize the Fremen prophecy of a savior who will come and turn the desert into water. We are never given any insight into whether any of these prophecies are true, and the author makes sure to let us know that neither do any of the characters, but nevertheless, the characters strive to realize these prophecies and, in many cases, succeed. The tension between the truth of prophecy and our desire to fulfill it is potent in Frank Herbert’s work, and it says something about the power of religion as an enduring force that influences human beings.

But Frank Herbert isn’t making some grand point about the triumph of religion over godlessness, nor is he explicitly condemning the non-religious. In fact, Herbert remains ambiguous about whether the religions of the main characters are forces for good or evil, and he treats them with the subtle complexity they deserve. I think Herbert’s point in making religion the center of the Dune world is simply to say that religion is here to stay. We can dream all we want of a world where we cast away the “irrational” shackles of spirituality and look towards science for truth, but Herbert thinks that the power of spirituality and the grasp it has on our imagination and on the human condition in general is too deep for it to disappear. The power of religion, the power of the idea of the world beyond our senses or of immutable ineffable truths, is not in danger of being replaced by science (as if the two were in comparable fields in the first place). Herbert rejects this Nietzschean idea of the decay of the place of God in society, claiming that even in the year 10191, humans will be as religious as ever, regardless of your opinion on religion.

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy: