In ‘Dear Ex,’ a tortured, extraordinary tenderness

February 18, 2022

Sophie Burchell

Sophie Burchell“‘A million years’ means: When he wants to be ‘normal’ one day and leaves you—after that day, every day is a million years.” — Chieh.

It is almost callous to describe the central tension in “Dear Ex,” the 2018 Taiwanese film, as a “premise.” Titled (more aptly, in my opinion) in Chinese as “Who Loved Him First,” the story, unfolding in the unassuming streets of Taipei adorned with folk temples and vendors of fried chicken chop, is told with such passion and humanity that its otherwise politically-charged theme of gay romance drew widespread critical acclaim on both sides of the Taiwan Strait.

It tells the story between the widow Liu San-lien (Hsieh Ying-hsuan) and Chieh (Roy Chiu), the male paramour of her late husband Sung Cheng-yuan (Spark Chen), who is a dashingly irreverent theater director. Sharing the devastating grief for the love of their lives, a dispute over Sung’s final decision to list Chieh as his life insurance beneficiary quickly sends the plot into brutally honest interrogations of homophobia, parenting and marriage. The film’s genre of cartoonish comedy-drama belies its true identity as a tear-jerker, one that delivers unrelenting gut-punches.

A rare gem in the tiny niche of Chinese-language LGBTQ films, “Dear Ex” eschews socio-political lectures for the most tender elements of humanist storytelling. It boasts carefully crafted flashback sequences and heartfelt portrayals of an all-too-accurate image of nagging Asian parenting, threaded together by a rebellious teenager dealing with confusion and grief. The audience will not find tenets of equality being recited and regurgitated; instead, the powerful, unmistakable commentaries lie beneath directors Mag Hsu and Hsu Chih-yen’s intimate understanding of life in Taiwan and the realities that shaped each character. The back-and-forth shifts between humorous caricatures and excruciating pains are handled with such deftness and sophistication that the elements never clash, but subtly complement one another.

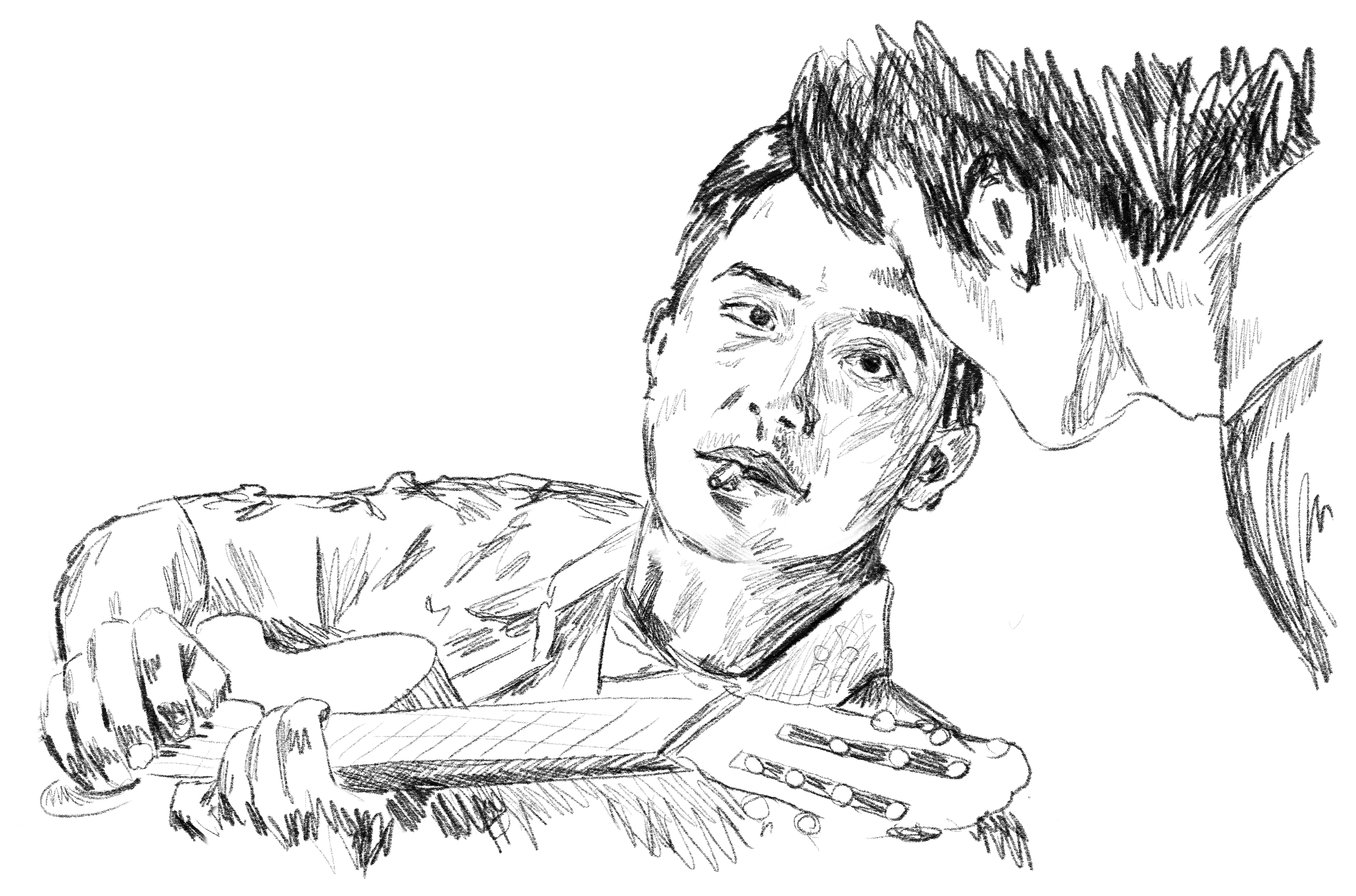

In particular, the performances from its leads are nothing short of extraordinary, helping the film in relaying its nuanced message wrapped in carefully articulated themes. Hsieh’s performance as the ordinary, grief-stricken mother, both anxious about her son’s uncertain future and outraged by her husband’s clandestine betrayal, won her Best Leading Actress at the 2018 Golden Horse Awards, the most prestigious Chinese-language film award. Chiu, for his part, constructed with sincerity Chieh’s new-age masculinity, walking a satisfying line between a stoic nonchalance and his comically disheveled lifestyle, culminating in a final catharsis that appeals to the rawest of emotions for love and family.

“Dear Ex” is a trenchant probe into the narratives of modernity and, broadly, a meditation on what it ultimately means to love and be loved. Few materials tell this story better than gay couples in Taiwan, who gained the right to marry, a first in Asia, six months after the release of the film. And while the film maintains an apolitical façade, its setting is a bold one: at the core of oppositional forces to gay rights in many parts of the Chinese-speaking world and beyond is the ugly assertion that gay people are amoral home-wreckers responsible for the disintegration of straight marriages—or, if allowed in, the institution of marriage itself. By tackling head-on the story of a husband’s extramarital affair from the perspective of gay men, it centers the narrative on structural inequities and the immutability of sexual orientation, a fact too often ignored or dismissed.

The film is acutely aware that its feel-good ending does not imply the end of the queer movement in Taiwan. By confronting lucidly spots that spell particular pain such as closeting, outing, ridicules and the casually-held prejudice and cruelty against gay people, it hints at what activists, queer theorists and queer people themselves have been feeling and enduring: among other things, the malaise of unbelonging and the fear of dying alone.

Perhaps the most comforting fact is that for the first time, Chinese-speaking queer audiences are starting to see a world on the big screen where even when the wait and the hurt feel like a million years, there are still moments of pure humanity and intimacy capable of redeeming the worst of odds.

“Dear Ex” is available for streaming on Netflix.

Some Chinese translations were omitted due to site inability to support Chinese characters.

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy: