‘Euphoria’ delivers glitter, but not much beyond

February 4, 2022

Content warning: The following contains discussions of sex, nudity and addiction; as well as spoilers for the season two premiere of “Euphoria.”

The premiere of the second season of “Euphoria” finally hit television over winter break, at a similarly unhinged juncture in real life—quickly depleting stocks, COVID tests, soaring case loads and declining public trust. So much so that venturing to stomach this infamously dark HBO teen drama can seem positively masochistic; at its core, “Euphoria” espouses a cataclysmic and gloomy logic that very much mirrors our own pandemic-infested times.

I binge-watched the entire series over break, tucked away in Southern California, the “Euphoria” locale whose flattering and unscrupulous reputations alike boast plenty of sex, violence and a specific strand of resplendent glamor.

After a two-year hiatus, the Sam Levinson drama returned with an unmistakable impulse to double down on shock value and gore. But behind its usual instincts to horrify the pearl-clutching crowds, the sophomore season betrays an anxiety that “Euphoria,” having left its slick aftertaste in pop culture’s wake almost two years ago, is now struggling to say anything of substance.

In the Scorsesian opening scene of the new season, we are greeted with the backstory of one of season one’s supporting characters, Fezco (Angus Cloud), with Kathrine Narducci (of “The Irishman” and “The Sopranos”) as his gangster grandmother. True to the “Euphoria” modus operandi, the scene features gushing blood from bullet wounds, an iconic female center, shockingly neglectful parenting and plenty of nudity, including an exposed penis (the first of many in the mere hour-long episode; a later showing during a particular bathroom scene quickly ascended to Twitter sensation).

To be sure, “Euphoria” is not the only show known to indulge in these elements in its storytelling. What had won the show critical acclaim has largely persisted: it has a good sense of not only eliciting emotive responses, but also utilizing cinematography with such dexterity that the audience becomes immersed in the Euphoric universe.

Zendaya continues her dazzling performance as Rue, whose rollercoaster relationship with Jules (Hunter Schafer) brilliantly captures the emotional center of the show. Her nihilism reaches new heights when a cardiac arrest scare following an overdose is only narrowly averted by crushed-up Adderall stacked in her socks (“There it is, there’s my heart … hello, heart, thought I’d lost ya.”). But the creative drive of the show has focused so intensely on the zeitgeist of “edgy” entertainment that nondescript outbursts or nonsensical subplots, neither enriching nor humorous, now dominate over its heartfelt realism—the style in which the central angst and trauma of the show shines through best. The gratuitousness of “Euphoria” belies its own message, and left unchecked, very few of its titillating (or downright horrifying) flirtations with graphic violence or toxic-nudity-in-abundance is justified. Instead, they come across as either meaninglessly dreadful or bizarrely pornographic.

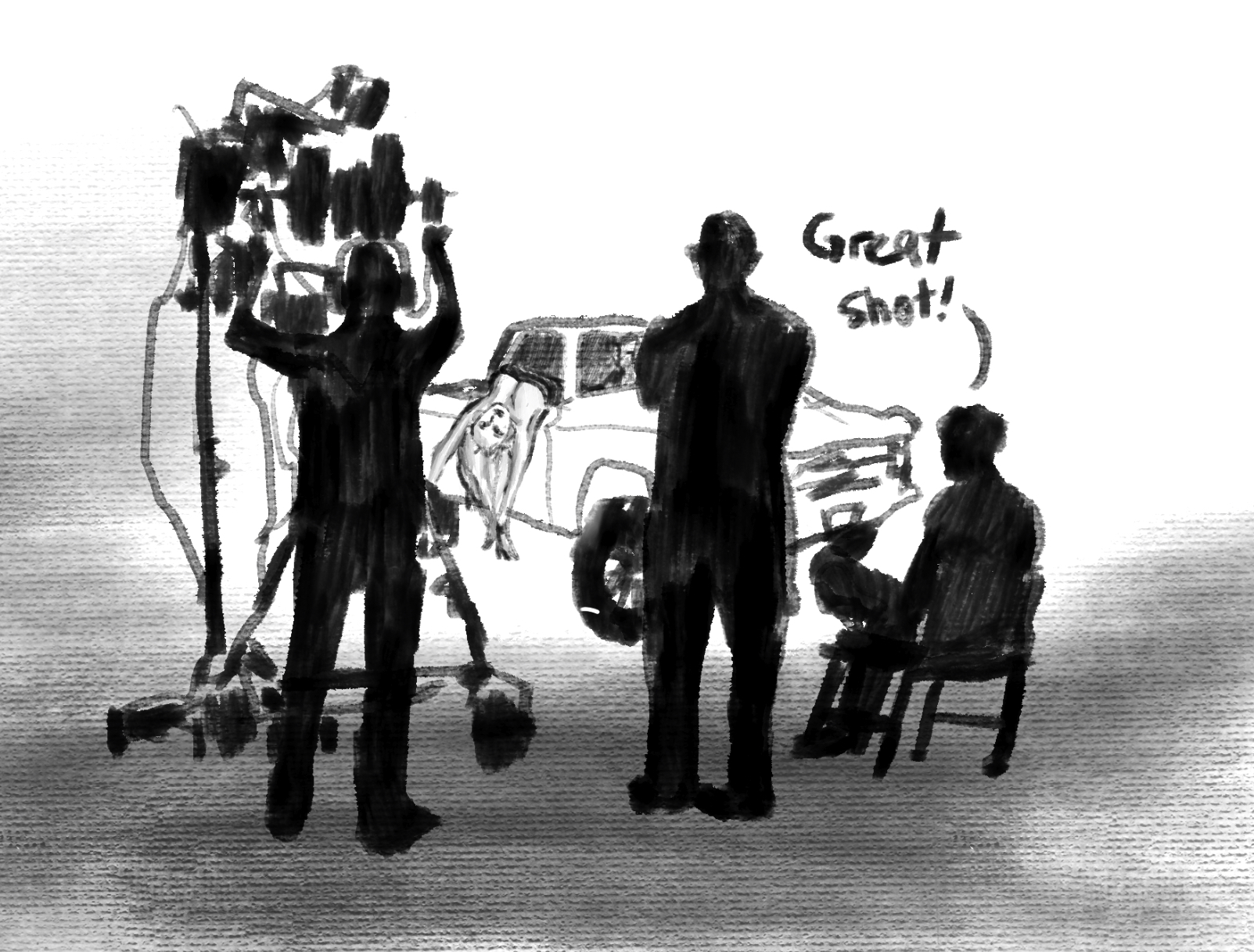

The show’s doubling down on flimsy displays of violence and sexual assault thins out character refinement for momentary thrills. Even when the stereotypical characters are buoyed by the show’s unique twists, it confuses extremity with nuance. This is best seen in Cassie’s (Sydney Sweeney) inexplicable car scene with Nate (Jacob Elordi), the psychosexually frustrated jock-predator with an abusive upbringing. It is troubling to imagine the show’s writers, most of whom older men, depict a barely-of-age girl sticking her head out a car window while undressing to vie for the sexual attention of a voyeuristic drunk driver speeding at 100 miles an hour. The entire image reads like a parodic caricature rather than careful character-building, suggesting a baffling idea of how shock value works and where the line is between captivating shocks and perplexing horrors.

The essence of Euphoria is well-taken: at times cathartically violent and at times grotesquely intimate, the show depicts unorthodox teenagers and their casual cruelties, hoping to medicate away the unrelenting brokenness of the American dream (or just their relationship dramas). But its carefully crafted visuals and cinematography suggest an ambition that is often derailed in the absence of the tenderness that holds down the fort. The danger of drifting from realism and indulging in shock and gore for its own sake is not Levinson’s creative agency in choosing when and where to show cruelty, assault or bare skin, but rather the troubling obsession with trauma that crosses from trauma awareness to trauma porn. Any social commentary made by the show would be overshadowed by its own schadenfreude: that is, the cruel reality that the unrelenting dread pervading the show has, in fact, always been capricious and irredeemable to start with.

The second season of “Euphoria” airs on HBO at 9 p.m. ET on Sundays.

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy: