Abbott Laboratories, COVID-19 and mass surveillance

September 17, 2021

This

piece represents the opinion of the author

.

This

piece represents the opinion of the author

.

Kyra Tan

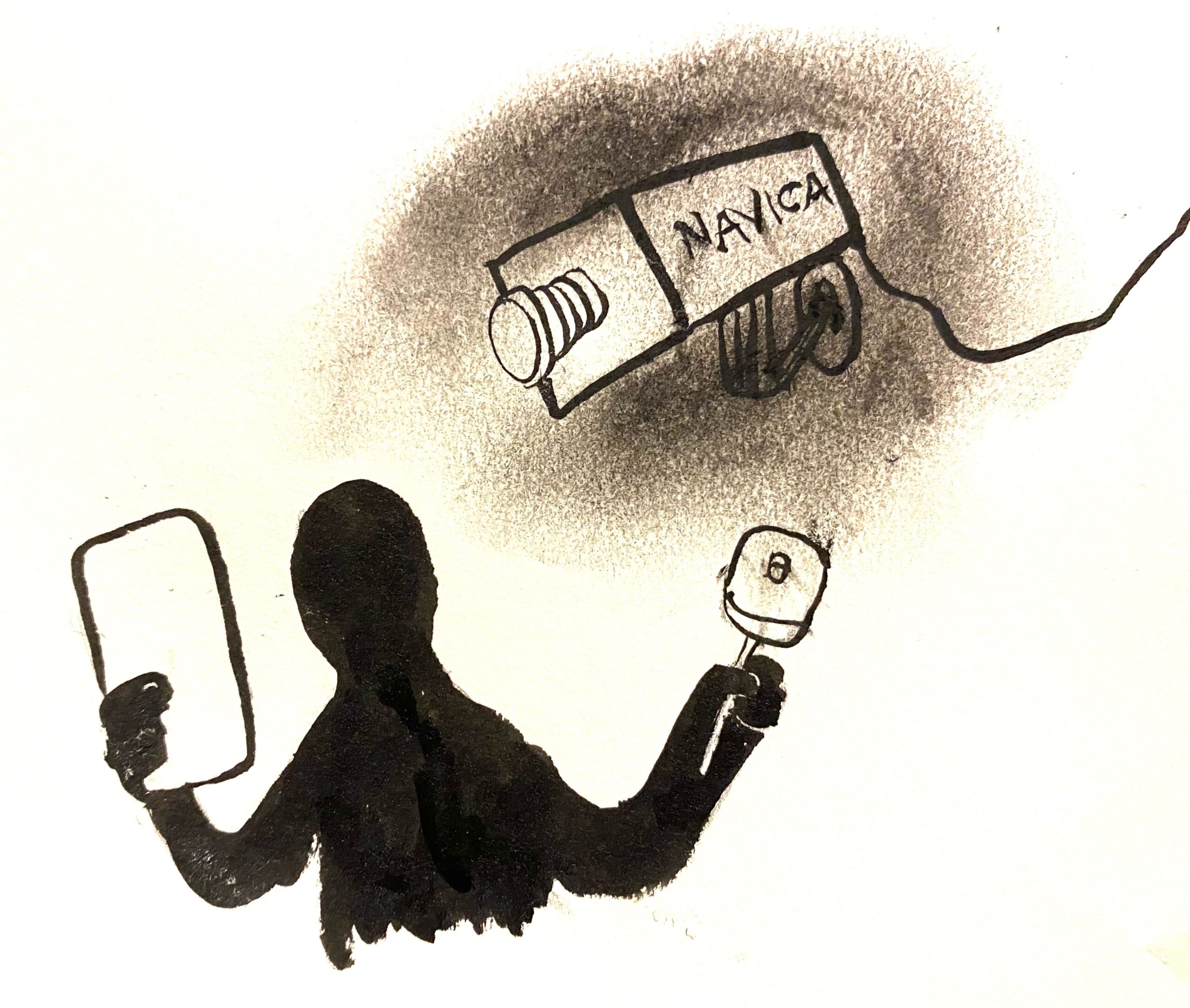

Kyra TanMost people and businesses use surveillance technology unawares, largely a result of how surveillance has “crept” into technology. What I propose to call Surveillance Creep operates in three phases. First, a company decides to collect information about its users. Second, those users fail to respond to the invasion of their privacy, usually because they aren’t aware of it, or, even if they’re somewhat aware, they fail to appreciate the scope of surveillance, and thus cannot accurately judge privacy practices. Third, as the company continues to build surveillance into its products, users who depend on the products come to depend on the surveillance and become desensitized to it. Often, there are better alternatives to what the company provides that are privacy-conscious.

Bowdoin College has forwarded the creep of surveillance into daily life, particularly through the technologies it uses to control the COVID pandemic. Consider Abbott Laboratories, the corporation which administers the NAVICA app that the College will use to manage COVID test results of close contacts on campus. Abbott’s end goal is to draw “inferences… [from your] personal information… to create a profile reflecting your preferences, characteristics, psychological trends, predispositions, behavior, attitudes, intelligence, abilities and aptitudes.” You can find this statement about 30 seconds deep into their privacy policy.

To be clear, Abbott “[does] not sell your personal information. However, [they] share personal information with [their] vendors, contractors, business and service partners, [and] other third parties … [including] analysis firms, advertisers, payment processing companies, customer service and support providers, email, IT services and SMS vendors, web hosting and development companies and fulfillment companies … [and] co-promotion partners … [from] other companies.” Why not throw in the kitchen sink?

I’m sure the College did not contract with Abbott with an intent towards surveillance. Rather, they probably proceeded without giving much consideration to and without understanding the scope of Abbott’s surveillance. It is the College’s duty, however, to realize the immense dangers of surveillance capitalism and to work against it. For example, instead of giving students take-home antigen tests and using trained practitioners at eMed.com to ensure that tests are correctly administered, students could instead walk to Farley Field House, have personal interactions with people from the community and not have to deal with eMed’s so-called “anonymized” health data sets. I should mention that even though Abbott’s NAVICA division collects less health information, Abbott’s own policy could supersede any current or altered privacy policy of NAVICA.

The three characteristics of surveillance creep are further displayed in the College’s use of the CLEAR app (separate from Abbott’s NAVICA app) to store proof of vaccination for campus visitors. CLEAR is a biometric surveillance company with an invasive privacy policy, and the College, again, seems to be unaware of the scope of CLEAR’s surveillance and the breadth of the information that CLEAR collects. The College devotes only one sentence to explaining how CLEAR handles your data, stating that “the vaccination information you provide to CLEAR is not shared with third-party partners … and is just used to generate a red or green Health Pass for screening purposes.” This claim is incorrect: CLEAR’s privacy policy states that “the CLEAR Health Pass may collect, use or share personal health information.” Moreover, because CLEAR has not made public the source code of their software applications, users have no means to verify how CLEAR handles the data that they collect.

There’s a better alternative to the CLEAR app: ask all visitors to wear masks, and let paper vaccination cards suffice as proof. The College finds both these steps to be adequate: masks are required for visitors, and, “for those without smartphones,” paper vaccinations suffice. Visitors to Bowdoin—which include high school minors—should be given an honest representation of CLEAR, which, by the way, could verify your identity using a combination of, and not limited to: 1) your location, triangulated using GPS, WiFi and/or Bluetooth; 2) your IP address; 3) your device’s unique advertising identifiers; 4) your device’s unique hardware identifiers; and 5) your unique walking gait, as fingerprinted using your device’s accelerometer.

The COVID pandemic has unfortunately led to many surveillance projects masquerading as health projects, as well as health projects which inadvertently surveil. As we likely will have to live with COVID for some time, we should re-evaluate some of the more invasive measures we have been willing to use to curb it. In fact, given that vaccines prevent most hospitalizations and deaths (though there is still no data about prevention of long-term COVID), I think we should stop using invasive systems of control related to COVID. The more desensitized we become to giving central authorities access to our personal information and daily activity—for example, through contact tracing apps or “vaccine passports”—then the less power, and, frankly, determination—we will have to stop invasive practices.

As we get used to surveillance, and as it becomes more purposefully integrated into everyday products, we will, in time, become dependent on the surveillance itself. Coffee makers ten years ago made good coffee and didn’t contain microphones. Coffee makers now might still make good coffee, but also happen to listen for your voice commands. While I can’t guarantee that coffee makers of the future will make good coffee, I can assure you that they’ll be programmed to feed you good conversation. The only way out would be to forgo the coffee machine—and coffee—altogether. And if you didn’t know already, humans aren’t good at giving up coffee, nor are they good at giving up the pleasure and fantasy that modern technology can provide.

Surveillance has implications for democracy. Consider Abbott’s NAVICA program, where users can be allowed or denied entry to a “NAVICA-enabled” location after presenting, at an entrance, a NAVICA-generated QR image encoding whether or not they recently tested positive or negative for COVID. Imagine if Abbott were to decide to generate “COVID positive” QR codes for people it didn’t like. Abbott, just like CLEAR, has not made public the source code of their apps, making their complete functions unverifiable. Beyond the still-small reaches of NAVICA and CLEAR, consider Amazon, built on amassing data about people’s lives. They know so much about each individual and have so much broad control, and that’s not a good combination for democracy.

The best thing Bowdoin can do to counter mass surveillance, besides educating its community, is to use services that don’t surveil students. Instead of giving students Google’s cloud storage, for example, the College could host its own cloud storage using privacy-respecting Free and Open Source software platforms, such as Nextcloud; instead of letting Microsoft Outlook read our emails and fingerprint, to a high degree of accuracy, the style of our writing, why not teach students how to encrypt their emails following the common “OpenPGP” (Pretty Good Privacy) encryption standard? We have a long way to go regarding mass surveillance; its pervasiveness, in fact, indicates that people are drawn to it. As an educational institution devoted to the Common Good, the College ought to help.

Lorenzo Hess is a member of the class of 2023.

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy:

- No hate speech, profanity, disrespectful or threatening comments.

- No personal attacks on reporters.

- Comments must be under 200 words.

- You are strongly encouraged to use a real name or identifier ("Class of '92").

- Any comments made with an email address that does not belong to you will get removed.

Hi Lorenzo. Opinions on the police?