Without College funding, athletics kept up the fight 100 years ago

September 25, 2020

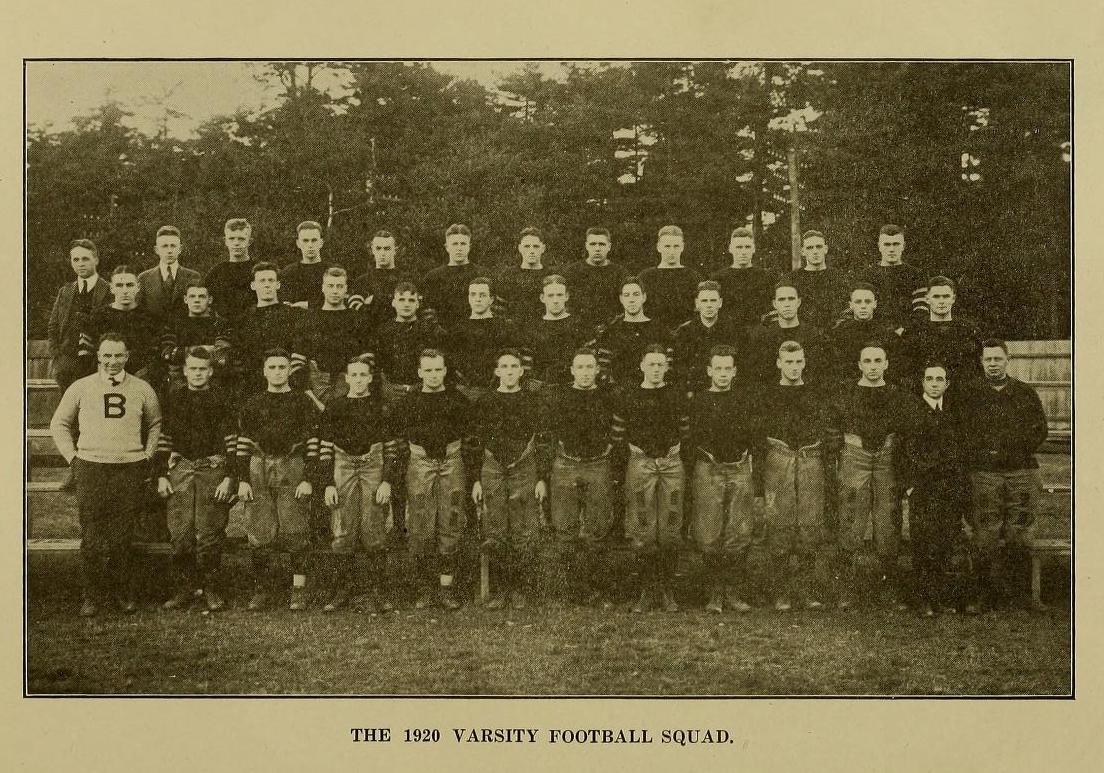

Courtesy of Bowdoin Special Collections and Archives

Courtesy of Bowdoin Special Collections and ArchivesFootball, cross country, track, baseball, tennis and ice hockey. In 1920, almost all of these Bowdoin athletic teams were funded by a committee outside the College’s budget—the Bowdoin Athletic Association (BAA)—without direct support from the College. Athletics, however, were just as important to the student body as they are today, and inter-class intramurals were central to the Bowdoin experience.

With only 465 male students—women were not accepted until 1971— in the Bowdoin community, athletics and competitions dominated the social sphere and were some of the students’ favorite pastimes. Since the first inter-class and intercollegiate baseball games in 1861, competition has remained central to the Bowdoin athletic psyche.

The disconnect between coaches and the College frustrated then-president of the college Kenneth C.M. Sills, class of 1901, who began his own battle against the BAA to gain control of athletics when he became president in 1918.

“I desire to repeat the recommendation made two years ago, that as soon as it is possible and practicable the salaries of coaches should be placed on the College budget,” wrote President Sills in his 1921 Report of the President.

The fight for control over athletics was not new in the 1920-1921 academic year, explained John Cross, the secretary of development and college relations and the College’s unofficial historian.

“President Sills, in the 1920s, was always complaining that Bowdoin alumni were perfectly happy to have the Alumni Council pay coaches more than they paid faculty,” said Cross in a phone interview with the Orient. “He was always working against that.”

Cross explained that Sills always pointed to the cross country and track teams as an example of why athletics should be under the College’s umbrella, as they were the most successful sports teams and received support from the College. However, he didn’t achieve this goal until the 1930s.

The year before, one George Russel Goodwin, class of 1921 and a member of the track team, finished sixth in Olympic Qualifying race for the 1920 Antwerp Olympics, and Head Coach Jack Magee traveled to the Olympics with the United States team in 1920 as an unofficial assistant coach.

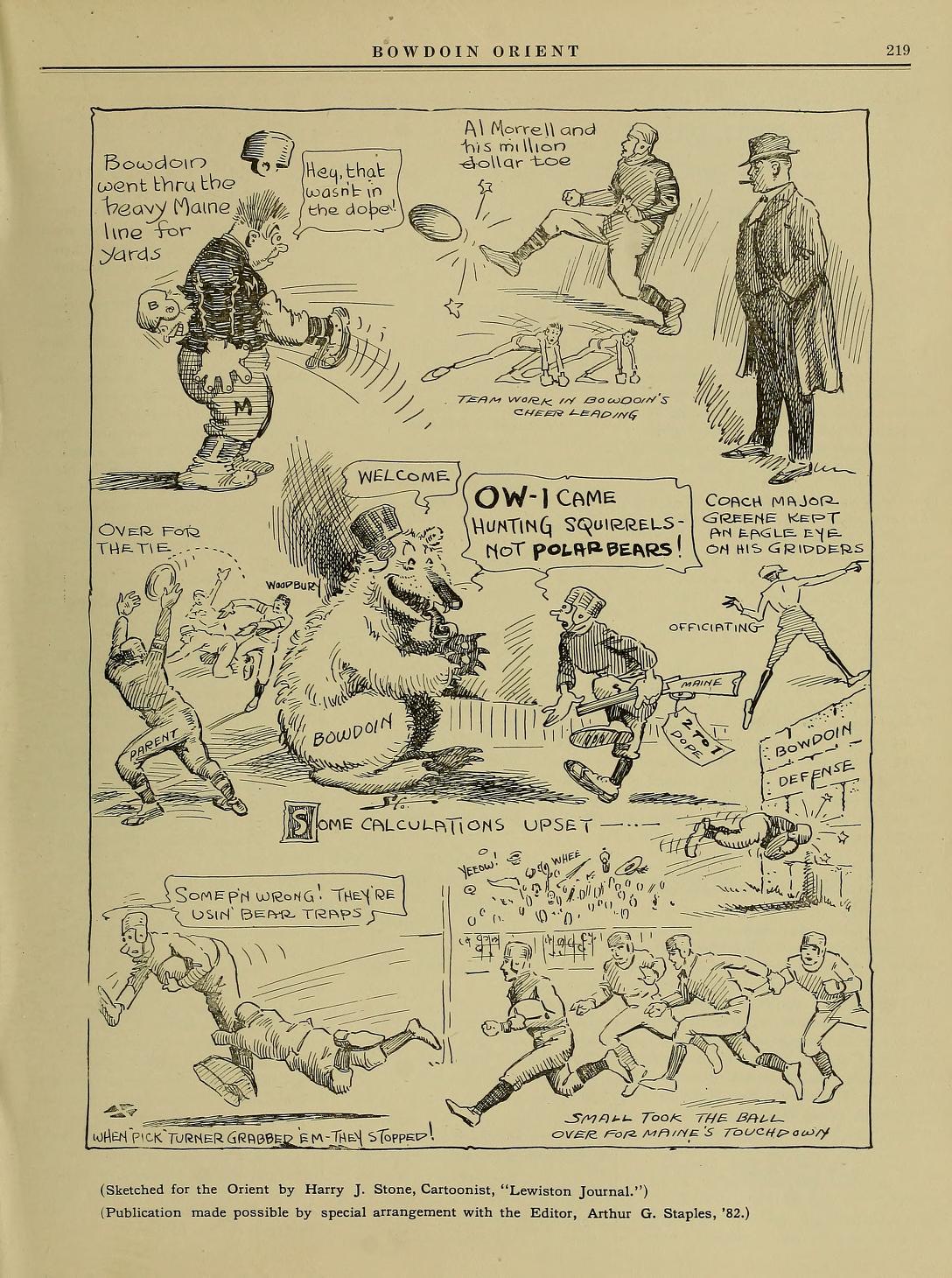

The football team, however, dominated the student body’s attention and procured the most coverage in the Orient’s sports section.

“They won two, lost four and tied two,” Cross said. “They did not have much offense. All season long they scored 20 points in eight games.”

Courtesy of Bowdoin Special Collections and Archives

Courtesy of Bowdoin Special Collections and ArchivesThe season got off to such a terrible start that Head Coach Major Roger A. Greene wrote an article in the Orient to assuage concerns from the Bowdoin community.

“Only four letter men [returning starters] are on the squad,” Greene wrote in Issue 14, Volume 50 of the Orient. “And the remainder of the first string men must be developed and injected into the machine [of the team].”

The team managed to turn it around soon after that article was published and after a win against Colby, Athletics Editor Floyd A. Gerrard, class of 1923, seemed optimistic about their chance to win the Maine Championship, a round-robin competition between the four colleges in Maine at the time: Colby, Bates, Bowdoin and the University of Maine. However, they did not pull off the championship and tied Bates and the University of Maine to come in second.

Despite the focus placed on football, the real competition of the 1920s was centered on intramurals and, more specifically, inter-class competitions. Throughout the course of the fall semester, the classes of 1923 and 1924 competed against each other in best-of-three football series and other, more dangerous competitions.

“There was something called a ‘Hold In’, which was when the sophomores tried to keep [first years] from leaving the chapel,” Cross said. “There would be sort of riots and broken bones and bruises and cuts and everything else. It’s a rough and tumble thing.”

Cross emphasized that hazing was definitely a problem, and this is a key example of how it manifested in the athletic sphere, pointing out that the reason behind these inter-class competitions was based on the way academics were structured.

“The curriculum used to be very specific. There were almost no electives. So even though you were a sophomore, you had a pretty much prescribed set of courses to take,” Cross said. “Even though you saw people from other classes around campus, the people you saw in the classroom were your own cohort, so there [was] a stronger sense of class identity.”

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy: