The day I stared at the putrid face of racism

September 25, 2020

This

piece represents the opinion of the author

.

This

piece represents the opinion of the author

.

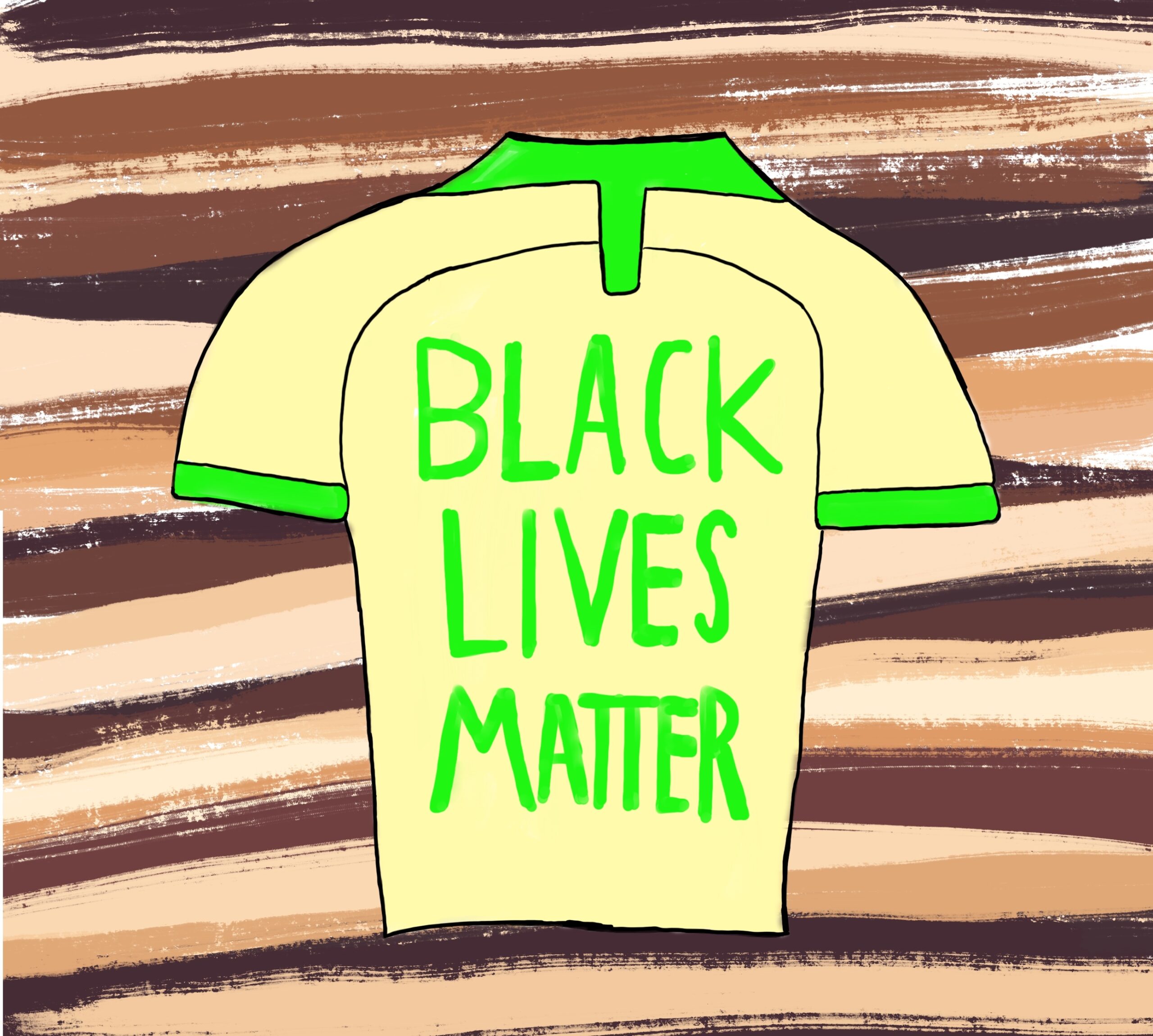

One of the most beautiful jerseys added to my collection over the summer became a canary yellow “19/20 Brazil” jersey stamped with a green print reading Black Lives Matter on the back. My body proudly displayed this jersey on August 16, a cloudy afternoon somehow perfect enough to go walking and hunting for Eevees on Pokemon Go. Unfortunately, a man in the passenger seat of a moving red car near a Market Basket openly disagreed with my jersey’s content when he uttered, “Not true fulano! All lives matter!”

As you may have noticed, the English language does not have the word “fulano” (generic Spanish term for “dude” or “stranger”). This exchange, in the Spanish language, came from a light-skinned brown man who discontentedly stared me down as his car drove away. That day, I stared directly at the repugnant face of racism, but not in its most typical form.

The tragic murder of George Floyd on May 25 of this year became another death in the long history of crimes committed by police authorities. Sadly, Floyd was not the only victim of police brutality around this time. On May 19, police in Puerto Tejada, Colombia, brutally beat 24-year-old Anderson Arboleda to death for violating the country’s curfew rules. A few days before Arboleda’s death, police in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, abhorrently shot 14-year-old João Pedro Matos Pinto while he played outside of his home.

Although alarming news to some, deaths like those of Arboleda and Matos Pinto are daily occurrences in Latin America and the Caribbean, a region of the world plagued by centuries-old systemic racism and authoritative violence targeting Black, often low income, Latin Americans. The region’s complicated racial issues stem from the historical refusal of many governments in acknowledging racial disparities, which comes from Spanish colonial systems that also created major economic inequity. Although many Latin American countries’ constitutions (Brazil and Colombia included) now have anti-discriminatory clauses, the political instability of each respective country has made it difficult for many of them to be truly implemented.

Nicholas Huang

Nicholas HuangIf one were to walk down a populated city street in Latin America, they would probably see a palette of different skin colors, all with a diverse history of origin. However, in this diversity also thrives a racial hierarchy of colorism. Toxic ideas, such as that of Mejorar La Raza (Spanish for “bettering the race”), imply that one should marry a lighter skinned person in hopes of having “fairer and better looking” children. This common philosophy serves as one of countless examples of how racism culturally manifests itself in Latin America and the Caribbean.

As a Peruvian immigrant, it would be extremely hypocritical to condemn systemic and cultural racism in the United States but not condemn it in my region of origin. Unlike past Latin American generations, we cannot overlook the structural racism which thrives in our culture. The Black Lives Matter movement does not subtract from our own movements (e.g. Chicanx) here in the United States or Latin America, and saying that it does willingly deletes the intersectionality of the Latin American identity. Phrases like “Brown Lives Matter” as a response to Black Lives Matter decenter and incorrectly appropriate BLM as well as create unnecessary tensions between two marginalized communities both fighting for equity. We cannot ignore Blackness from the history of our region because doing so reinforces the dangerous anti-Black belief that Black Latin Americans do not exist.

As modern day Latin Americans, we have a duty to stand with and support the Black Lives Matter movement because it demands justice and equity for our Black lives which have been ignored and neglected by our culture and governments for so long. Black Lives Matter. Anderson Arboleda matters. João Pedro Matos Pinto matters. There should be no buts or ands.

To Bowdoin’s Black community, I will never fully understand your struggle, but in the same way Martin Luther King Jr. extended his support to Cesar Chavez through a telegram in 1966, I extend my own support: “Our separate struggles are really one—a struggle for freedom, for dignity and for humanity…We are together with you in spirit and in determination that our dreams for a better tomorrow will be realized.”

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy:

- No hate speech, profanity, disrespectful or threatening comments.

- No personal attacks on reporters.

- Comments must be under 200 words.

- You are strongly encouraged to use a real name or identifier ("Class of '92").

- Any comments made with an email address that does not belong to you will get removed.

I’m sorry this happened to you. This kind of slur is unfortunately all too common.

Where did this happen? If it happened on or near Bowdoin property, you should report it to the security or someone from college.