Why my dad didn’t say he loved me, and why that’s OK

September 11, 2020

This

piece represents the opinion of the author

.

This

piece represents the opinion of the author

.

Dalia Tabachnik

Dalia TabachnikLike many other Bowdoin students, the second half of my spring semester became an unusual mix of awkward online classes, dreading trying to find a summer job and fear of the coronavirus reaching the doorstep. Unfortunately, COVID-19 decided to visit my household, and thus for a major part of it, I stayed locked inside my tiny room binging on “Rick and Morty” and fried plantains.

However, the biggest anomaly of my already strange summer did not come in the shape of a virus but rather from a text message my dad sent me, which read, “Buenas noches hijito, te quiero mucho” (Goodnight my son, I love you). Although this sounds like a standard exchange between a father and son, these were words my dad typically never said or wrote to me. At first, this realization led to resentment and, most importantly, questioning why this was the case. However, after months of reflection, conversations with other Latin American friends and some research into my family’s past, the case of this anomalous text led me to some important cultural revelations.

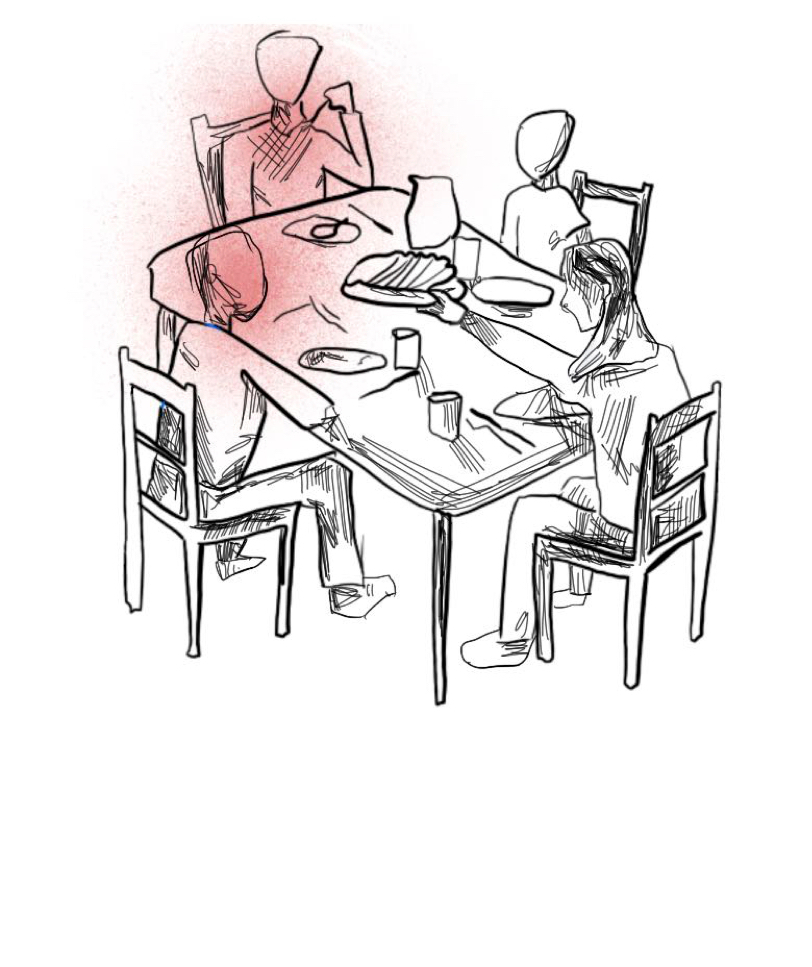

My dad grew up in a strict military household in Pilcomayo, Peru, during the bloody rise of the Shining Path, a terrorist organization. Even after we immigrated from Peru to the United States, he never truly expressed affection, often disciplining anything short of what he, as the head of the household, deemed excellent. Because of our often conflicting schedules, we grew distant from each other and only regularly saw each other for Saturday night dinners.

The complicated nature of this almost businesslike relationship with my father did not truly strike me until I reached Bowdoin, where during move-in day I saw a big difference between how my classmates and I interacted with our parents. Before they left that day, I promised my parents that they would receive a call from me twice a week. These two calls a week became the most important factor in connecting with my father and ultimately the key to understanding him.

Latin American men, due to the machismo (overt masculinity) passed down from generations before, often reject their emotions as signs of weakness. Because no guide exists for parenting, Latin American parents often raise their children in the way their own parents raised them with zero questions asked. In extremely difficult situations, like immigration, the toxic belief that emotion equates to weakness often becomes reinforced.

Could one then blame my father, a man who did not have the luxury of compassion in his younger years because of armed military conflict, for not expressing his emotions? Emotional vulnerability is a privilege that immigrant parents, particularly men, simply cannot afford in a country where they must fend for themselves, often with little to no resources. In the case of my father, his challenge became finding the American Dream while having to raise two children to be better than he is in a country where he could not speak the primary language.

My father may have never verbally expressed that he loved me, but he showed it through every one of his actions. His long work hours may have strained our relationship, but what choice, especially in our situation, was there? He did everything, both the good and the harsh, out of love for his family. Because of his sacrifices, I can proudly call myself a Bowdoin student.

As modern-day Latin Americans, we have a duty to break the archaic cycles of hyper-machismo that have been sown so deeply into our culture. Due to the isolation that often comes with immigration and raising a family, our parents/parental figures may have us as their sole sources of emotional support. Honest communication with them becomes absolutely crucial in creating the dialogues once deemed taboo to them. Perhaps we cannot change the philosophy of our parents or people we deem parental figures, but we can surely change it in ourselves for our future families.

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy:

- No hate speech, profanity, disrespectful or threatening comments.

- No personal attacks on reporters.

- Comments must be under 200 words.

- You are strongly encouraged to use a real name or identifier ("Class of '92").

- Any comments made with an email address that does not belong to you will get removed.

Thank you for sharing this, Carlos ?

This reminds me of an article posted on NYT titled “Why We Struggle to Say ‘I Love You’” which runs parallel to this piece from an Asian POV.