Casting my lot with religion in the age of climate change

February 28, 2020

Adrienne Rich (1929-2012) was a renowned feminist poet throughout the second half of the 20th century. Her poems explored themes of feminism, social justice, queerness and environmentalism. One of my favorites is called “My heart is moved.”

“My heart is moved by all I cannot save: / so much has been destroyed / I have to cast my lot with those / who age after age, perversely, / with no extraordinary power, / reconstitute the world.”

Two of the most influential people in my life, a married couple who teach at my public high school, introduced me to this poem. They recited it to my Community Activism class, a class they designed together and have been co-teaching for 15 years in an effort to expose students to activism—both at the community and global level—and inspire them to become changemakers.

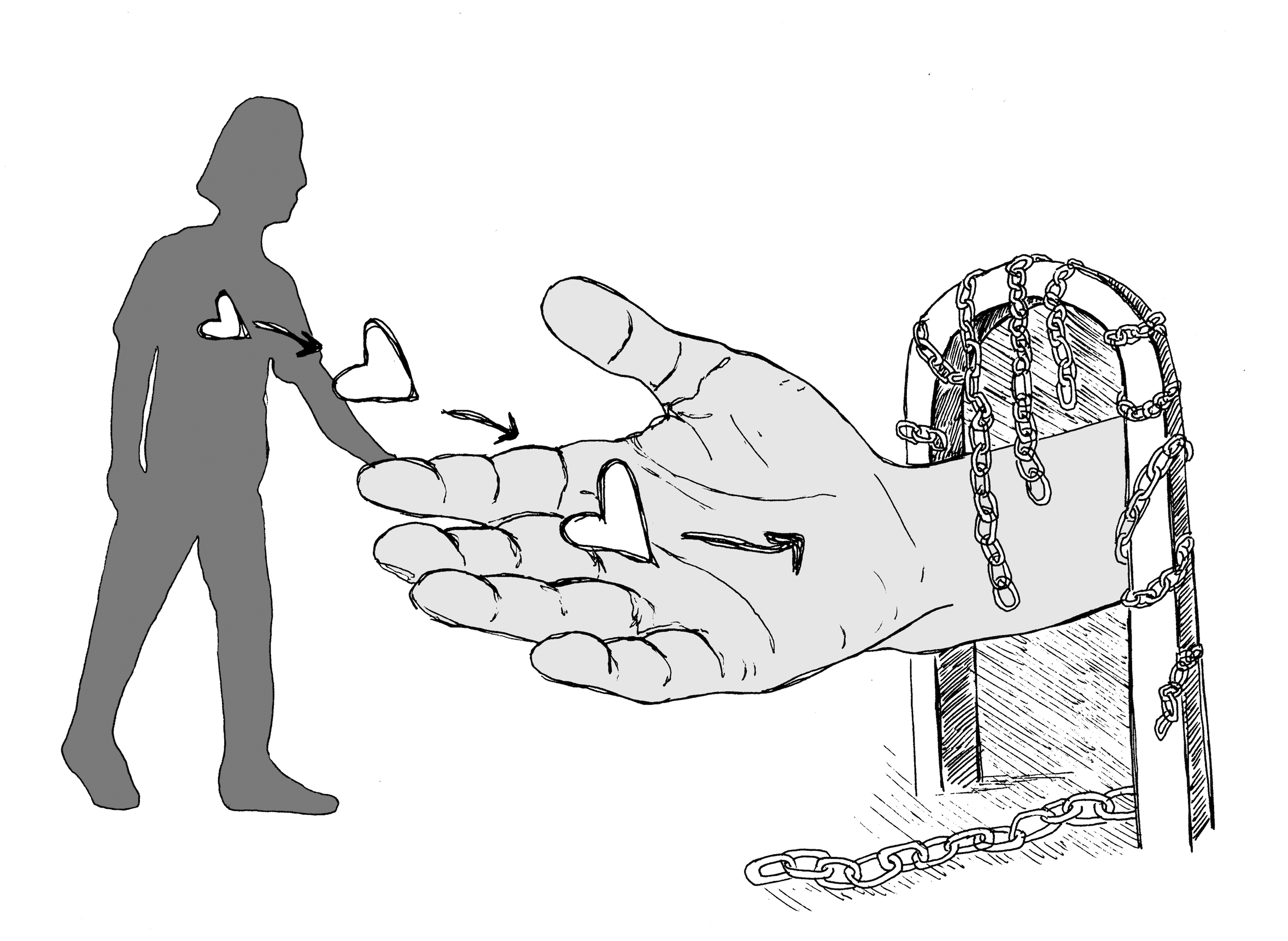

I was reminded of this poem recently when I attended a conference at the Yale Divinity School called the Graduate Conference on Religion and Ecology. Mary Evelyn Tucker founded the Forum on Religion and Ecology, which was responsible for this annual conference and has put out multiple publications, textbooks, an Emmy award-winning documentary and a website which includes statements from every major world religion on climate change. When Tucker recited Rich’s poem during her keynote speech, I smiled from ear to ear and mouthed the words as she spoke them. She used this poem to frame the fundamental questions we would discuss at the conference: How do we grieve all that we have lost and will continue to lose in the face of climate change, structural inequality and injustice? How do we move forward in the face of such destruction? What role might religion, spirituality and faith play in all of this?

For me, these questions were not confined to the conference, they are questions I ask myself every day. As an Environmental Studies major and senior searching for ways to apply this education to my life’s work, I think about Rich’s poem as a spiritual doctrine that can guide me in this journey.

Rich’s poem gives me permission to feel grief and mourning for “all I cannot save,” it encourages me to look to the “extraordinary” power of like-minded individuals around me. The word “reconstitute” conveys that we are always reforming, restoring and reconstructing a broken world but implies that this work will never be finished. My favorite word in this poem is the word “perversely,” which connotes radicalism and resistance. This work requires challenging entrenched power structures, narratives and norms. My Community Activism teachers used to joke that they were turning all their students into perverts.

The Graduate Conference on Religion and Ecology was full of perverts.

One woman presented on the power of empathy and examined how various religious traditions teach us to have empathy for the earth. A farmer explained how he teaches youth to farm in ways that are grounded in Jewish tradition and teachings. An activist presented her works to protect public water resources against privatization and how that relates to her philosophy as a pastor. During the keynote lecture, an indigenous woman advocated for decolonizing Western science and re-centering indigenous knowledge in the environmental movement.

The conference presenters were fully aware of what they were up against—a hegemonic Western worldview (some even called it a theology) characterized by privatization, capitalism, commodification, colonization and extreme individualism. It is a worldview which puts the economy at the center and prioritizes profit above the health and dignity of humans and our environment.

At Bowdoin we love talking about how much neoliberalism and capitalism suck, but sometimes it feels like we’re at an impasse, and we don’t know how to proceed. We slip into hopelessness, cynicism and despair. During one of the workshops, someone asked a question I often ask myself: “So, what do we do? How do we go forward in the face of such destruction caused by capitalism and corporate greed?”

The indigenous woman who had given the keynote presentation earlier piped up in response. She replied that we should look to indigenous people. “Our apocalypse already happened,” she said. “What did we do? We just kept going. We still just keep going.”

To me, that is the message of Rich’s poem. It is about putting one foot in front of the other, no matter how dark the road ahead may seem. But it is also about casting my lot with those who have gone before me on this road: indigenous people who survived colonization and genocide, African Americans who survived chattel slavery and Jewish people who survived the Holocaust, to name a few. Their post-apocalyptic survival and persistence is an inherently perverse act.

Climate change is just the latest apocalypse. The difference is that it will affect everyone, even those who have historically had the privilege of being spared. Walking down this road is a deeply spiritual journey that tests our limits of compassion for each other and for the Earth. The good news is people have already walked this road, each step forward being an act of faith, hope, courage and perverse resistance. Let us look to them for lessons and let them lead. Kayla Snyder

Kayla Snyder

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy: