Looking back: women make a place for themselves in Bowdoin Greek life

September 27, 2019

It’s officially fall. Apple picking season has descended upon us, frisbees litter the quad and College House residents are finally settling into their castles on Maine Street. The same houses, I might add, which many years ago were home to fraternities; famous members of these organizations include William S. Cohen and Joshua Chamberlain.

Bowdoin’s nine College Houses all once belonged to nationally-recognized fraternities, with the exception of Alpha Rho Upsilon, Bowdoin’s sole local fraternity. Fraternities employed well-known rushing and recruiting practices for potential new members and took part in standard features of commonplace Greek-life such as throwing campus-wide parties, hosting meals and even hazing.

Louis Hatch’s “The History of Bowdoin College,” published in 1927, records that the College had 11 fraternities, but this number eventually fell to nine full-time fraternities complete with live-in members, dining contracts and house duties. These nine fraternities grew in size and popularity as Bowdoin expanded, and by the mid-1960s more than 95 percent of the student population identified as fraternity members.

That is to say, Bowdoin’s model looked nearly identical to our country’s standard Greek life narrative—with one major difference.

While Bowdoin’s first fraternity was founded in 1841, the College did not become coeducational until 1971, 130 years later. Women had to force their way into the institution’s social scene. Many did so by joining Bowdon’s historically all-male fraternities.

That’s right. Women joined fraternities.

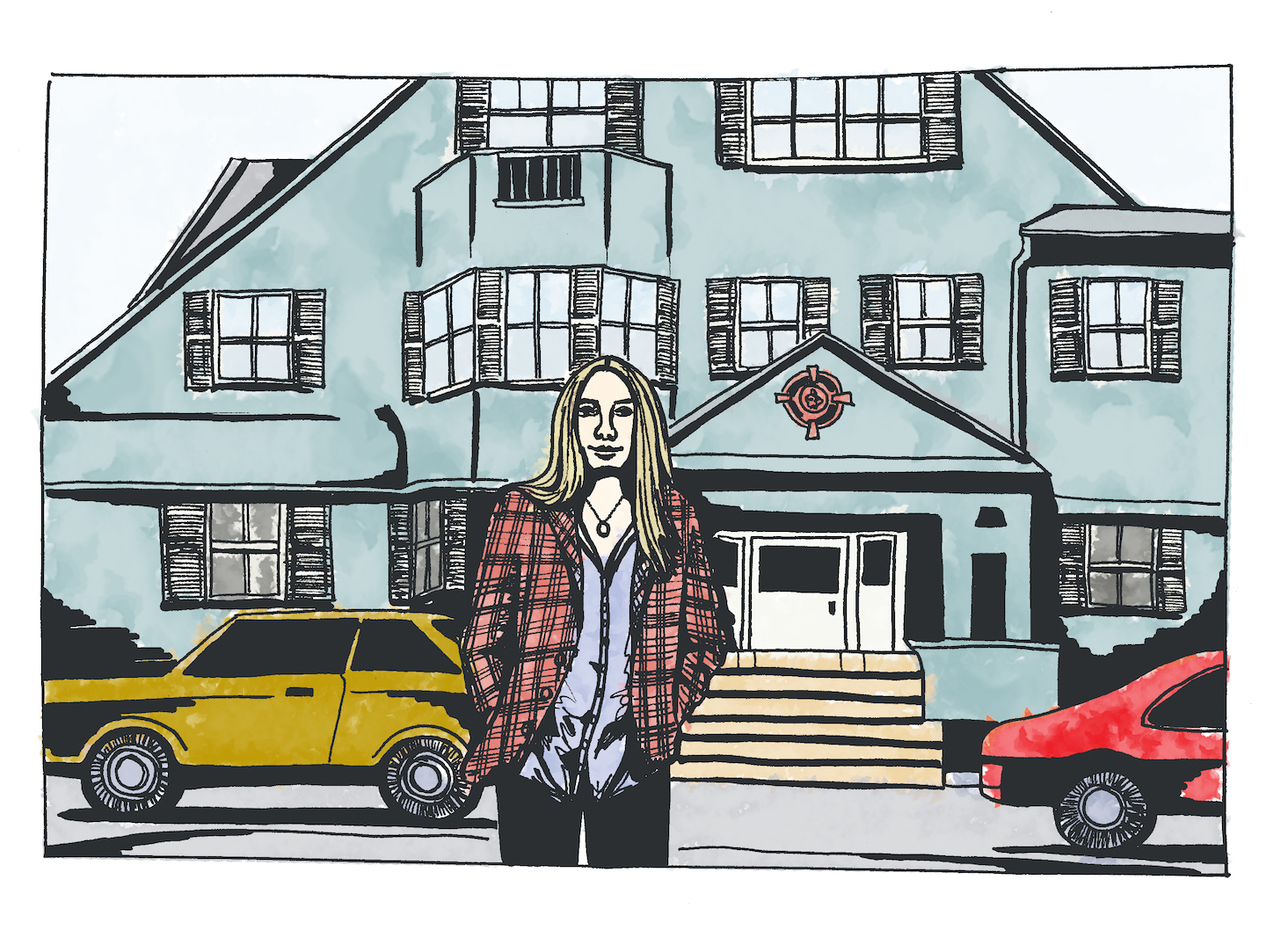

Sixty-five women joined 254 male first-years (and roughly 900 male students total) at Bowdoin’s matriculation ceremony in 1971, becoming members of the College’s first coeducational class. Among them was a young woman named Patricia “Barney” Geller ’75.

Geller began as a dishwasher in Psi Upsilon but would become chapter president of that same fraternity in the spring of her first year at Bowdoin. Not only was Geller the first female president of a fraternity at Bowdoin, but she was also one of the first female presidents of a nationally affiliated fraternity. Once the national chapter caught wind of the fact that Barney Geller was, in fact, a woman, Bowdoin’s chapter became embroiled in a national scandal.

Geller was not the only woman to forge her own path in Bowdoin’s male-dominated social scene. Laura Carl ’84 pledged Alpha Delta Phi during the fall of her freshman year and became one of a growing number of women to challenge historic fraternity rules. She would later become her chapter’s in-house historian.

In a phone interview, Carl said that even though Bowdoin was mostly male when she attended, ranks of women pledged fraternities and just about half of the officers in her fraternity were women. Bowdoin was experiencing a significant shift in its culture, and multiple fraternities began accepting women despite national chapters being all male. Alpha Rho Upsilon, another popular fraternity, established itself as completely accepting of all genders and races and declared its Greek letters to be an acronym for “All Races United.”

The point here is that Bowdoin’s history of Greek life was not the norm. Women in the United States were rarely presidents of nationally-recognized Greek organizations, they did not often sit at the dinner tables of their own fraternity houses and enjoy meals with their brothers and they were not usually tasked with inviting dates to frat dances.

This is not to say that gender discrimination did not exist at Bowdoin. It certainly did. Including, if not especially, in the realm of Greek life. Some fraternities only allowed women to join as “eating members” or social members and did not permit women to vote in house matters, while two other fraternities maintained their all-male status years after other fraternities became coed. And while some fraternities allowed female members to hold office, the number of female presidents during this time was discouragingly low.

Taking this history into consideration, the only sure conclusion seems to be that Bowdoin Greek life defies our country’s traditional Greek life narrative due to strong and early female involvement in the social scene. While Geller broke down barriers for women countrywide, Alpha Rho Upsilon reinvented itself on unprecedented principles, and the Bowdoin community took coeducational expansion (somewhat) in stride.

So as we continue through the school year, walking the same paths that many of these female leaders from decades ago walked, the question is, how can we expand upon the groundbreaking work of women in the Bowdoin community and blaze our own path to change?

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy: