Free (www.)ill: the design of decision-making in the digital age

March 1, 2019

From the decision to get up in the morning to the decision to go to bed at night, our days are filled with choices. There are big decisions, like whether to move to a different city, state or country. There are smaller choices, like whether to eat at Moulton or Thorne. There are miniscule choices, like whether to respond to the Orient’s weekly poll. The course of our day, and likewise the people we meet along the way, are determined by these decisions.

But is there an intrinsic difference between the decisions we make in real life and the decisions we make online?

This week, I met with Fernando Nascimento, postdoctoral fellow in digital and computational studies, to consider these questions. Prior to coming to Bowdoin, Nascimento spent 25 years working in the tech industry, 17 of which were at Motorola, where he participated in the development and expansion of mobile device technology. Parallel to his career, he pursued his interest in philosophy by first obtaining a masters and then a Ph.D. focusing on ethics and hermeneutics.

I shared two articles with Nascimento beforehand: “The Illusion of Control in ‘Black Mirror: Bandersnatch’” by Howard Chai on Medium and “Holding Artificial Intelligence to Account: Will Algorithms Ever be Free from Bias if They’re Created by Humans?” by Matt Burgess in Wired. Like last time, I encourage you to read these articles for yourself.

“The difference with technology today is the acceleration,” Nascimento told me. “Things are getting faster and faster in terms of how technological artifacts are created and how they are deployed, especially because of mobile devices and online platforms. You can create a new app and, in a few months, tens of millions of people may be using that app. There is nothing like that in our past.”

Nascimento is concerned about this acceleration in comparison to the length of ethical discussions.

“Our ethical and legal discussions about technology are not going at the same pace as this acceleration,” he said. “One has to be careful about two non-productive extreme positions with regards to technology. The first one is that all technologies are evil; the second is that technology is a panacea. The goal of a profound reflection on technology is to look for the golden mean where technology becomes a positive force to human beings and the world.”

He pointed to the proliferation of data collection as one of the ways in which an ethical framework could be applied.

“People are producing a lot of data; companies are storing as much data as they want and there are algorithms that are getting more and more efficient at processing all this data. This triangle is what requires our attention,” said Nascimento. “It is very powerful. But who is giving direction to the power? How are issues related to privacy and data ownership being addressed? It is up to society to decide how to direct this discussion.”

Algorithms use data to learn users’ likes and dislikes, ultimately narrowing your options over time so that at some point you only see the things you liked in the past.

“This narrowing is problematic,” Nascimento explained. “There are at least two ways to reduce people’s agency: one is to remove options, the other is to give the options you want people to have. The second case is the worst case because your agency is decreasing, and you may not even realize it.”

Machine-built interpretations of reality thereby isolate the choices with which a consumer is presented during their interaction with the respective technology. Nascimento suggests that we need machine-built ways to distinguish when different types of manipulations occur. I asked for more clarification regarding the ethical framework that needs to be applied. Do ethical and legal frameworks necessarily go hand in hand? Can we have an ethical framework without the legal one?

“If we had a utopian society, the ethical framework would be just fine. If everyone complied with the ethical framework, there would be no need for a legal framework per say. But this is not the case,” Nascimento said.

“We need to include technology concerns in the discussion of how our legal frameworks are structured. On one hand, both our ethical and legal systems need to evolve faster to follow the ever-increasing pace of technological innovations. On the other hand, ethical concerns need to be included by design in new technological artifacts and architectures,” he explained. “Ethics needs to be a part of the technological design process. It’s not only about putting parts together and optimizing algorithms but thinking about how you are going to impact society.”

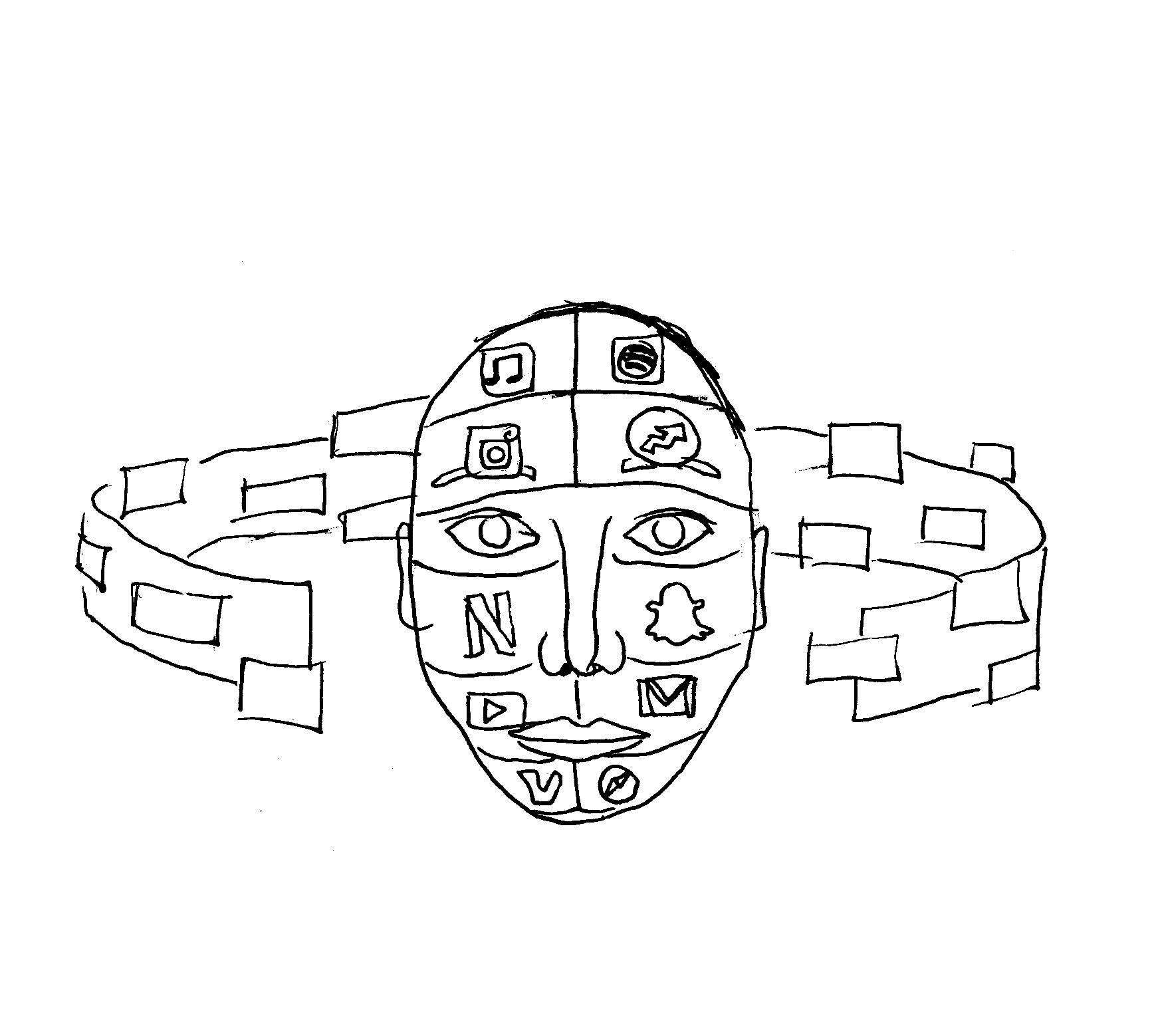

There are social implications related to the digitization of identity. Algorithms develop identities by correlating and modeling data points, but these are “closed identities,” closed because of their inability to capture and interpret unexpected, innovative and unique events. Nascimento suggests a narrative perspective as a necessary complement to these data-driven, quantified selves.

“Your narrative offers a privileged approximation to your identity and weaves together your many discordant experiences into an open concordant story, always being revised and in search for meaning,” he said. “Such narrative identity is impossible without including other people in your story … Today, we had this conversation and now I will be a part of your narrative. Both of our identities were changed, interconnected and interwoven because this particular event is now included in your narrative. I feel we have to discuss technology in the context of these narratives. In return, technology must become a meaningful part of our collective narrative.”

Whatever you decide to call it—progress, change or evolution—this narrative is not presently accounted for in algorithms from the most popular content providers.

Nascimento compared algorithms to debaters.

“We normally say that the winner of a debate is the person who convinces their opponent that their position is right. But what have they won? Their own opinion was already in place and has not changed. The person who has been convinced is winning because he is taking out of that debate something that he did not have before.”

He continued, “The one who has fixed convictions is somehow closed to the different, and algorithms tend to accentuate this difference. We have to work within technology and the algorithms embedded in these technologies to expand our horizons rather than reducing them to our past selves and the concordant opinions artificially selected by matching algorithms.”

Do we need algorithms for this? I don’t think so.

Accumulate opinion. Debate difference. We can all win.

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy: