‘Second Sight’ explores vision and accessibility

March 2, 2018

Jenny Ibsen

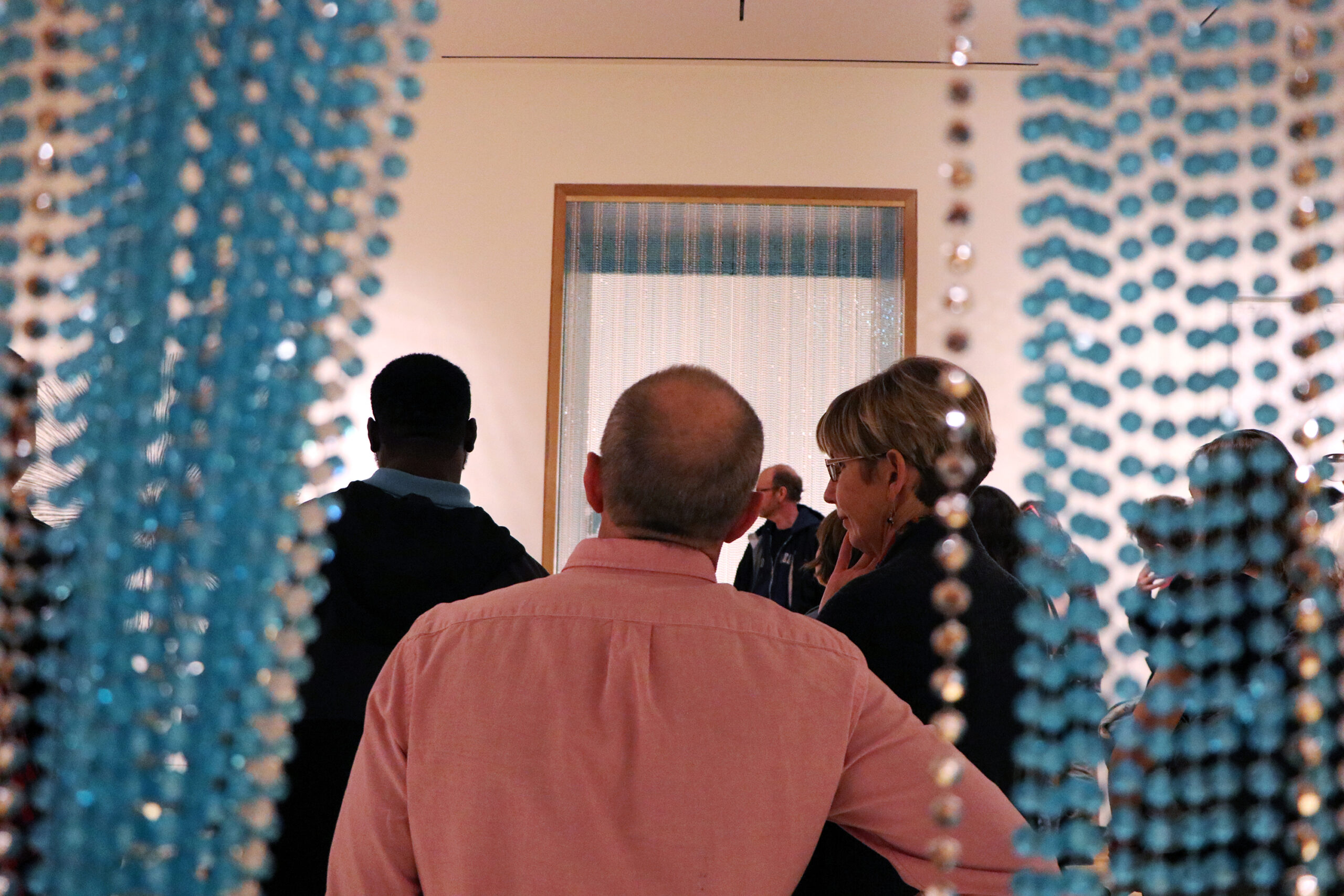

Jenny IbsenBoth the visual and nonvisual are on display in the Bowdoin College Museum of Art’s newest exhibition, “Second Sight: The Paradox of Vision in Contemporary Art.” Alongside its array of diverse and often abstract works—from beaded curtains hanging from doorways to auditory works of art—the gallery contains a series of “audible labels” played through an innovative device developed specifically for this show.

Andrew W. Mellon Postdoctoral Curatorial Fellow Ellen Tani, who curated the exhibition, set out to make the show accessible to low-vision visitors. She conducted research with the help of student interns including Kinaya Hassane ’19 and Maria McCarthy ’20, and consulted with artists who focus on accessibility, such as Canadian Social Practice artist Carmen Papalia.

“It was a long process of researching what we thought would be the best solution, what research tells us is the best solution and what we could actually do [with] the time and resources we had,” said Tani. “The initial thought when you’re making resources for low-vision audiences is to just do Braille labels, but most blind people actually don’t read Braille, because many people who are legally blind aren’t fully blind.”

Tani devised the battery-powered “labels” in collaboration with Bowdoin’s Information Technology. Each label consists of a 3D-printed earpiece attached to the wall with a magnet. When the earpiece is disconnected from its magnetic counterpart on the wall, the sound chip within is activated and the recording plays aloud.

Tani and museum interns took an equally thoughtful approach to the language of the labels, taking care to avoid purely visual references.

“We decided to do audible description, which is different than just reading the wall labels aloud,” said Tani. “It’s really conveying the presence of an artwork and what it looks like in language. And the editing process for those is really interesting because we had it to keep it very interpretive. We also had to be mindful of things like units of measurement that might not make sense to somebody who doesn’t reference those units. So talking about an artwork’s scale in terms of the dimensions of the body, or everyday objects that we interface with more frequently.”

For example, rather than describing a photograph in standard units of measurement, one label describes the size of the work by comparing it to a computer monitor.

The exhibition’s investigation of the nonvisual, which stemmed from ideas Tani had while working on her dissertation, features both work that is experienced non-visually and work that was created without the aid of the eye.

“In that sense, the nonvisual, or blinding oneself, becomes a way of accessing a different kind of creative space,” said Tani.

One auditory piece featured in the exhibition, entitled “Come Out,” was created by experimental composer Steve Reich in 1966. The piece uses the oral testimony of 19-year-old Daniel Hamm, one of six African-American youths known as the Harlem Six. All six were falsely accused, beaten by police and later convicted for murder on the basis of a forced confession. The six became a symbol of stop-and-frisk tactics and racial profiling that drove activism during the Civil Rights Movement.

The piece is a sound collage, created for a fundraiser for the retrial of the Harlem Six, featuring a fragment of Hamm’s testimony as he described having to expose his wounds so that the police would allow him to go to the hospital. The phrase “come out to show them” is played on two tape loops at different intervals until the phrase becomes unintelligible.

“The police refused to take him to the hospital if they didn’t have visual evidence of the injury,” said Tani. “The fact that his words didn’t mean anything, and that he had to show visual evidence… is something that the exhibition is engaging with at a critical level—the fact that we rely so heavily on the visual for verification, for the evidence, for facticity. That we discount the power of language.”

Though the works on display are diverse in medium and subject matter, they are carefully arranged so as to allow underlying meanings to emerge.

“I think what they all share in common is the artwork as a tool of critical thinking, both for the artist and for the viewer,” said Tani. “Because they present themselves in a way that can feel a little bit nondirect—they’re nonrepresentational, they’re using modes of abstraction, different modes of presentation that don’t give us an easy answer. If you’re willing to engage with the work and interrogate its materiality and interrogate its scale and exercise that critical thinking, you can access a new way of experiencing the world around you.”

“I feel like [these artists] are very successful in their efforts to connect these domains of knowledge and domains of sensory perception and realms of thinking and experience that we wouldn’t otherwise compare with one another,” Tani added.

Tani also discussed her efforts to complicate the narrative surrounding works by artists belonging to marginalized communities.

“One of the tendencies when we’re writing the art history and also when we’re writing criticism about artists of color is to essentialize the meaning of their work to matters of identity alone. And on the one hand, that does good work in the sense that it improves the visibility… but… if we’re holding up these artistic geniuses on this level, and the artists of color are over here doing work about identity politics, they will never come together and they will continue to remain separate historical narratives. So as an art historian, I’m really committed to bridging that divide.”

The exhibition represents the culmination of Tani’s work at Bowdoin. She will be leaving the College to work as an Assistant Curator at the Institute of Contemporary Art in Boston.

Aisha Rickford contributed to this report.

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy: