Professor Wheelwright’s “the Naturalist’s Notebook” takes flight

November 3, 2017

Meghan Parsons

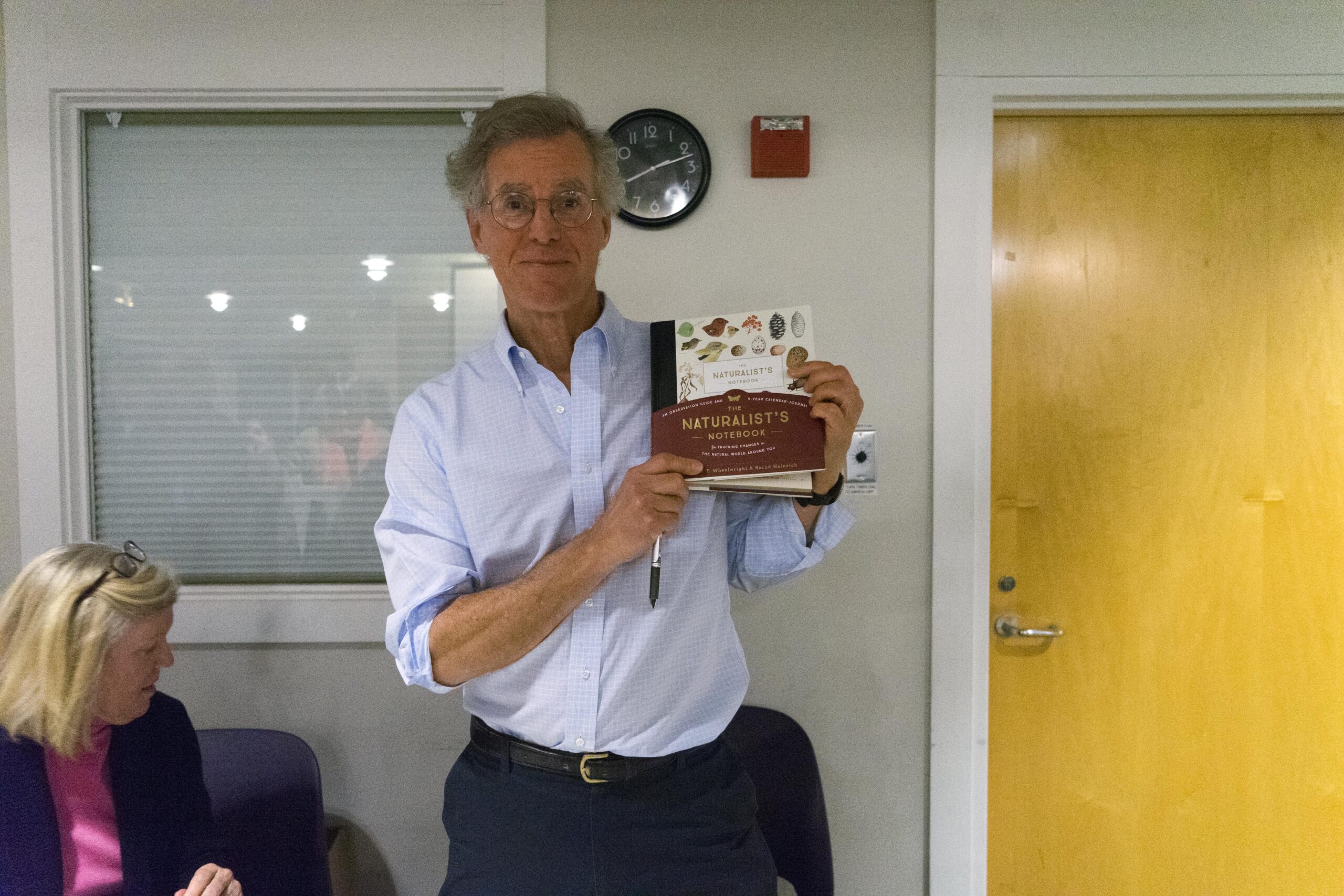

Meghan ParsonsNathaniel Wheelwright, the Anne T. and Robert M. Bass Professor of Natural Sciences, has practiced naturalism all his life. For Wheelwright, naturalism is more than a field of study: it is a way of experiencing and perceiving the rhythms and patterns of the world around him.

“I am not just a stone skipping over the surface, clattering along, but actually feel connection to the plants and animals that I see,” he said. “I notice small things: small smells, small sounds and it’s a sense of awareness and mindfulness and presence.”

Part of what connects Wheelwright to the earth and ecosystems around him is consistent nature journaling, a practice he began 29 years ago after receiving a ten-year garden journal as a gift from his sister-in-law. Ten years later, he asked for a second, and then a third. Five years after that, inspiration struck.

“I thought ‘I’m onto something here. This is really a good system,’” Wheelwright said. “‘How can I get this out to more people?’”

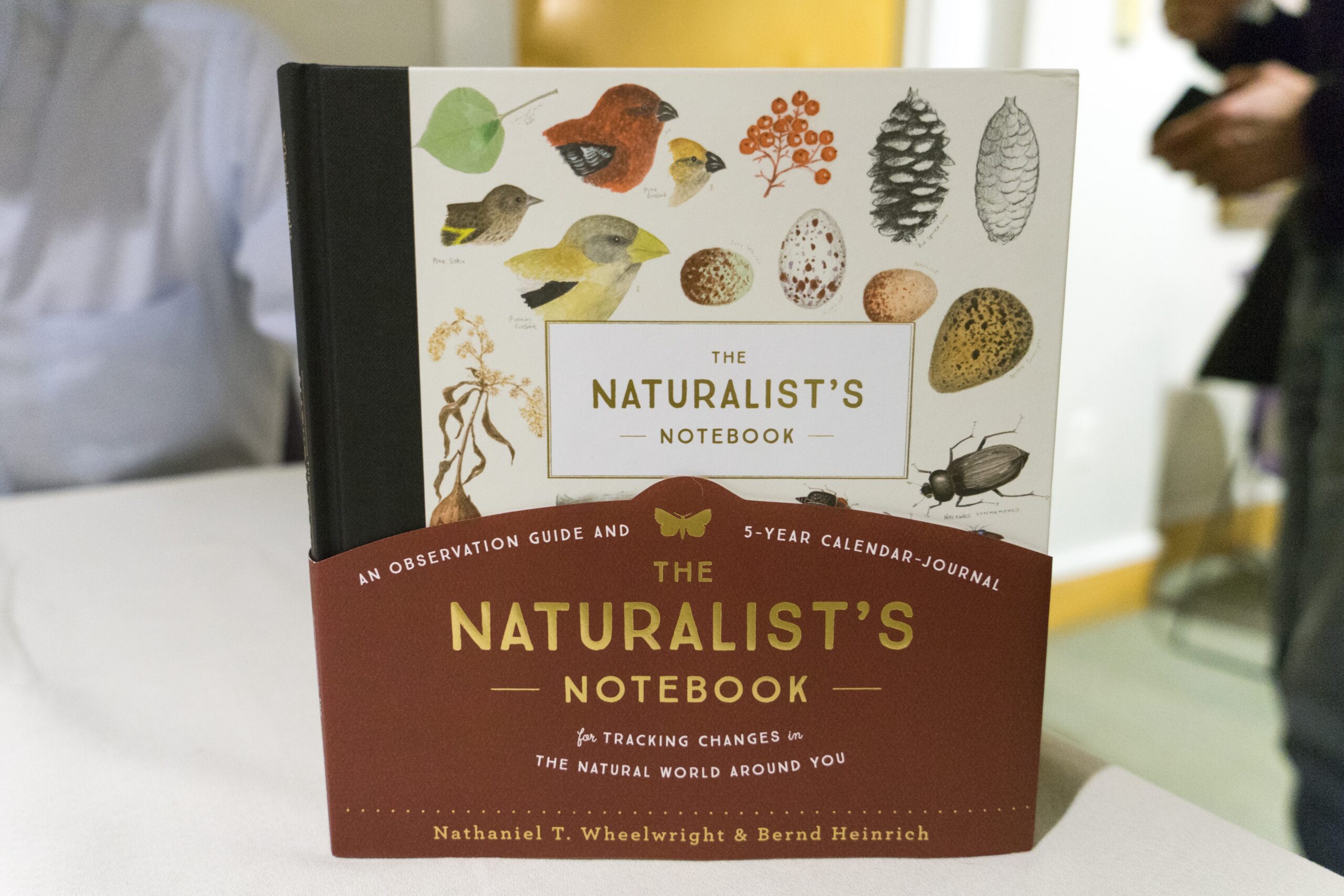

He spent the next four years answering that question, and on October 17 he published the result, entitled “the Naturalist’s Notebook,” with co-author Bernd Heinrich, an esteemed natural history writer. This Wednesday evening, Wheelwright spoke about the book at Curtis Memorial Library. He explained his inspiration to write the 200-page book, which is part nature guide, part five-year calendar journal for use by the reader.

“I’m like a lot of people who bought a black journal at some point, with nice beautiful clean pages and they vowed that they were going to pour their heart into it every day for the rest of their life,” Wheelwright said, “but it’s too much hard work to do it, and there’s too much guilt and they just stop dead in their tracks.”

Wheelwright’s book is different, designed to maximize ease through its simplicity. Wheelwright encourages his readers to use short, four-letter abbreviations to denote natural phenomena, eliminating the time and commitment required to keep up more comprehensive journals and notebooks.

He hopes that this approach will encourage readers to keep using their journals for years or even decades, as he has.

“Over time I could feel the rhythm of nature, and started looking at things like mosses and lichens and stuff that are not as charismatic to the average person, but once you sharpen your eyes, they jump out and they look like little rainforests,” Wheelwright said. “They’re just gorgeous.”

Combatting climate change and promoting conservation are two goals forever at the forefront of Wheelwright’s mind. He hopes that owners of “the Naturalist’s Notebook” will begin to look more closely at the examples of global warming, which he has noticed in his own backyard, like consistently delayed snowfall and frost.

“If people tell you that climate change is a hoax, you can verify [climate change] in your own backyard,” he said on Wednesday.

Wheelwright considers naturalism to be especially important in today’s world, populated by constant information flow and exposure to technology.

“It’s wonderful therapy for these discouraging times that we’re in,” Wheelwright said. “It’s like going into a library or listening to a concert – it’s puzzles: a hundred daily miracles.”

Technology has revolutionized naturalism. By snapping a photo with a smartphone and conducting a quick Google search, naturalists can identify specimens in seconds, thereby shortening a process that would otherwise take hours or days.

Wheelwright hopes that “the Naturalist’s Notebook” will encourage readers to re-engage with the world in tactile ways that have become rare in the information age.

“The physical act of writing makes for more enduring memories,” Wheelwright said on Wednesday evening.

Over the course of his 30 years teaching at Bowdoin, Wheelwright he has observed a decisive shift in the background of many Bowdoin students. Today, the majority of the student body comes from urban or suburban backgrounds, unlike Wheelwright’s upbringing on a Massachusetts farm.

“We shot animals and weeded driveways and cut down trees and spent all day outside just doing stuff with nature,” he said.

Without this background, many Bowdoin students lack substantial first-hand experience with naturalism.

“They’re probably less likely to be hunters or fishers and they come in with less knowledge, but what I have seen this year is that they come in with enthusiasm to re-engage with nature and learn more about it,” Wheelwright said. “If you combine that enthusiasm with their innate brains and industry, Bowdoin continues to turn out great ecologists and biologists and naturalists.”

Wheelwright has been on sabbatical since the end of the 2016-2017 school year and has spent his time away from Bowdoin producing a series of 90 second videos called “Nature Moments.”

“I’m busier than ever,” he quipped.

With the help of the Bowdoin Office of Communications and independent filmmaker Wilder Nicholson ’16, Wheelwright has published four videos for Maine Audubon, aiming to connect viewers with nature from the comfort of their homes.

“Particularly at the times where people think there’s nothing to look at, the [videos] are all about seeing things in nature that you might have overlooked,” Wheelwright said.

Both the “Nature Moments” and “the Naturalist Notebook” are labors of love for Wheelwright. He plans on donating all royalties from the book to the Organization for Tropical Studies, based at Duke University, the Maine Audubon Society and the Mass. Audubon Society, where Wheelwright worked as a guide at 11 years old.

Wheelwright will retire at the end of this school year. He plans on applying for a Fulbright fellowship in order to travel to Colombia, where he hopes to study local fauna and produce a Spanish-language version of “the Naturalist’s Notebook.”

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy: