The alum who stole Hitler’s books

October 27, 2017

This

piece represents the opinion of the author

.

This

piece represents the opinion of the author

.

Kayla Snyder

Kayla SnyderIn May of 1945, Joseph H. Johnson Jr. ’44 found himself shimmying down a rope into Adolf Hitler’s library. Once ornate with handmade bookshelves of wood and glass, the library had been moved from the second floor to underground, thereby protected by the body of the mountain when British troops bombed Hitler’s Berghof home five days before his death.

A few days later, in coordination with French troops, Johnson’s patrol was one of the first to reach the remains. Permitted to take a few “mementos,” Johnson swept his new possessions into a pillowcase: Hitler’s personal telephone book, a tablecloth, china dishware and five books, one of which, in a kind of poetic irony, was Dante’s “Divine Comedy.”

Bowdoin’s Special Collections and Archives now houses the five books, thanks to Johnson’s early years of affection for the College. (He would later develop the hobby of sending back empty alumni donation envelopes with snarky comments about the school’s liberalness.) Except for the Dante, the books date back to the 16th and 17th centuries.

On a Monday afternoon, after seeing one of the books in my English class, I hold their bones: the cover of the history of Alexander the Great is mottled like aged skin, the front engraving of Macrobius’ commentary browned and sticky, the Dante’s wavy body seemingly once waterlogged, as if the book itself had been through nine circles of hell.

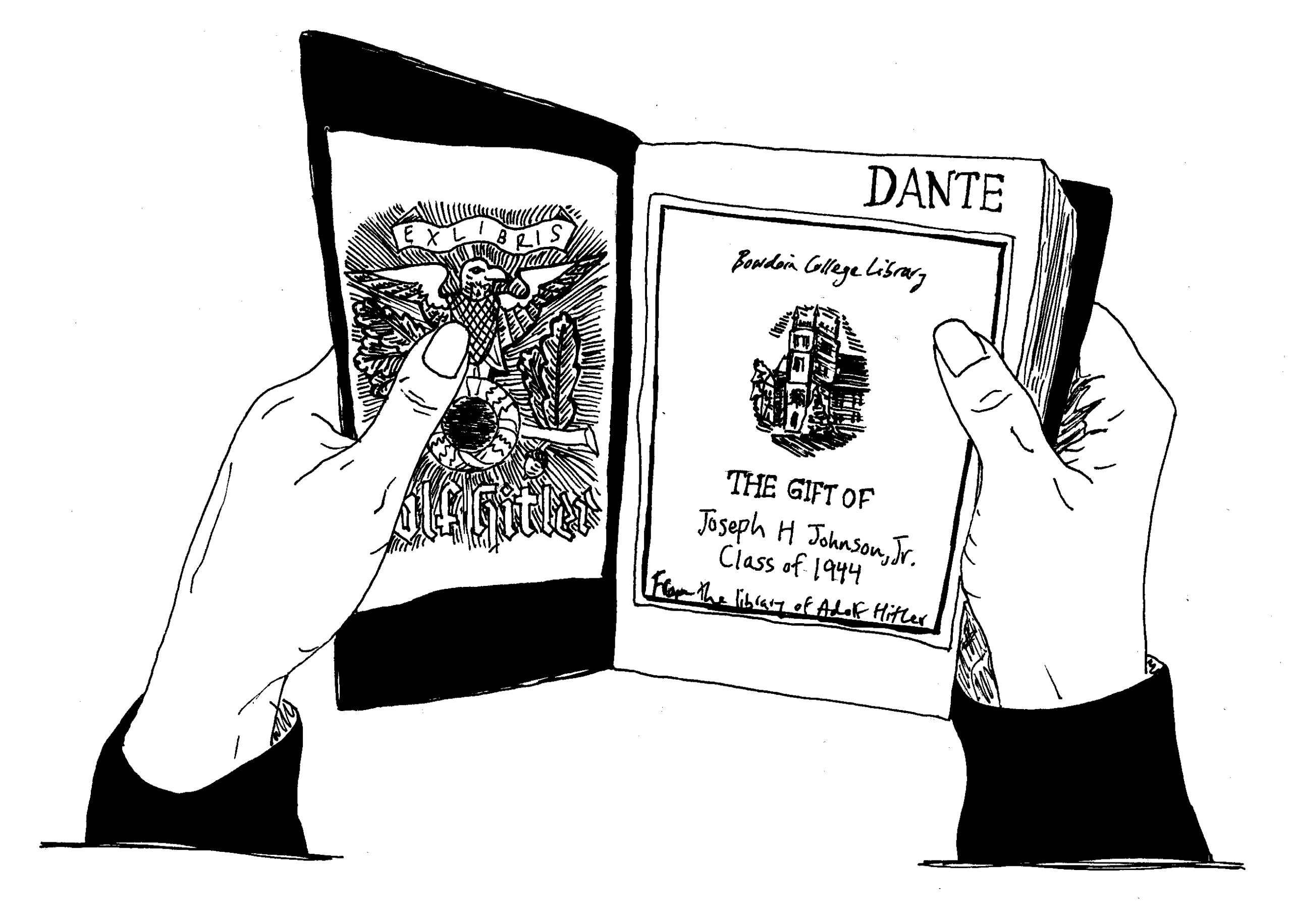

My hands feel dirty when I open the Dante to see Hitler’s bookplate: his name in fat font beneath a sharp-winged eagle who presides over a branch with a single acorn and a swastika. The Dante, once part of the Library’s general collection, also bears the College’s seal, embossed onto page 55 of every book up until four or five years ago. All five books carry the standard College bookplate—a sketch of Hubbard Hall—along with Johnson’s name. In pencil below, someone has written “From the library of Adolf Hitler.”

The physical books reveal the ways they’ve been possessed over the years, mixing up who stole, lost, gifted or received. Johnson may have owned these stolen books temporarily, but really, he was just a part of their lineage. I think about the way I write inscriptions on the inside covers of picture books for my two-year-old nieces. I fear that they won’t know me and know me well, and so I sign my name in permanent marker, impossibly claiming the books before passing them on, hoping some part of me endures.

Given the Nazis’ history of pillaging, these books, particularly the older ones, were likely not gifts, but rather taken from someone, ending up in Hitler’s library as symbols of intellect. Little research has been done on Hitler’s reading habits, curious considering how much one’s library can reveal one’s character. We do know, however, that Hitler’s Berghof library was one of the dictator’s three libraries and, notably, the one saved for his most valued volumes. And, while earlier research has failed to find any Dante in Hitler’s collection, the Bowdoin copy proves otherwise.

For Johnson, these books were gifts of doubtful value and use for his alma mater. In his letter to the dean about the books, Johnson wrote that perhaps “some Latin or German student may find use for them some day.” He didn’t suspect, as we rarely do in the moment, that their history of ownership—and Johnson’s part in it—would prove much more interesting.

Over 70 years later, I parse through Johnson’s file. I read about the way he developed from a boy, whose mother wrote letters to the dean blaming his failing two classes on illnesses acquired before age six, into an elderly man who unemotionally sold his appropriated Hitler possessions at an auction in Boston.

I read a letter from Bowdoin’s head of admissions kindly informing Johnson that not only was his application late, but that he had taken only one of the 15 courses required for enrollment. A year later, Johnson got his act together, attended and loved Bowdoin and then, along with many of his peers, took a leave of absence from the College his junior year to serve in the military.

Bowdoin assumed a curious role in Johnson’s life. His early warmth towards his deans in letters deformed into notes attached to alumni donation envelopes that denounced the College’s “political radicals, mentally incompetent blacks and neutered female destructionists” or reproached the College’s rejection of his son’s application.

The College, on the other hand, kept up its communication through personal sympathy notes following the death of said son and, 10 years later, the death of Johnson himself. “Bowdoin is a family college,” both letters read, “and whatever affects any one of us affects all of us in some measure.”

However impersonal this standard condolence is, these documents reveal the College’s persistence in Johnson’s life. Like the rest of us, Johnson may have claimed this school as his own for four years, but really, Bowdoin claimed him. The College embossed him with a class year, wrote a paragraph of his identity and stamped him with a bookplate, a sketch of a place that, at one time, served as a home.

These marks are some of many; the file doesn’t reveal the rest of Johnson’s life. Like the books, we are often possessed by places and people so temporarily. The books are presently squirreled away in the back shelves of Special Collections, but their permanent owner remains and will remain undefined. In my own life, this lack of tethering intimidates me. I suppose that’s the point of learning to be on your own. And yet, in the process of writing my own history, at least I have stamps like Bowdoin to carry with me.

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy: