You’re not that woke: on the importance of music, culture and self-doubt

April 26, 2017

This

piece represents the opinion of the author

.

This

piece represents the opinion of the author

.

Diana Furukawa

Diana FurukawaThe other day I came to the uncomfortable realization that I am not as woke as I had once thought. I’ve always held the belief that music simply reflects the values, circumstances and realities of whatever environment it comes out of. In an interview with Trevor Noah on “The Daily Show,” T.I. once espoused a similar opinion, saying, “Hip-hop traditionally has always been a reflection of the environment the artist had to endure before he made it to where he was. So if you want to change the content of the music, change the environment of the artist.”

I like this argument. It’s a great way to shut white people down when they come at you saying that violence in black neighborhoods is the fault of hip-hop music (and by extension, the predominately black performers who make it) and not the result of generations of housing discrimination, systematic racism and police brutality. It is an argument that I’ve relied on many times—and that is going to make it all the more difficult for me as I now go about dismantling it.

The notion that music simply reflects culture is productive in certain contexts but entirely untrue in others. Currently, I live in a house that hosts a lot of parties. At one such party, I witnessed an exchange that disheartened me. Drake’s song “All Me,” a favorite of mine, was playing through the small Bluetooth speaker that sat on the ledge of the faux hearth in my kitchen, and eventually it came to the point in the song where the beat drops off and the only sound that can be heard is Big Sean delivering his iconic line, “Ho, shut the fuck up!” As this happened, I watched as a boy turned to the girl next to him and, bringing his face in close to hers and smiling a dumb, drunken grin, shouted those lyrics right in her face. The boy was obviously quite amused with himself at having remembered the lyrics and successfully delivered them with the correct timing and cadence. The girl, on the other hand, did not seem so amused.

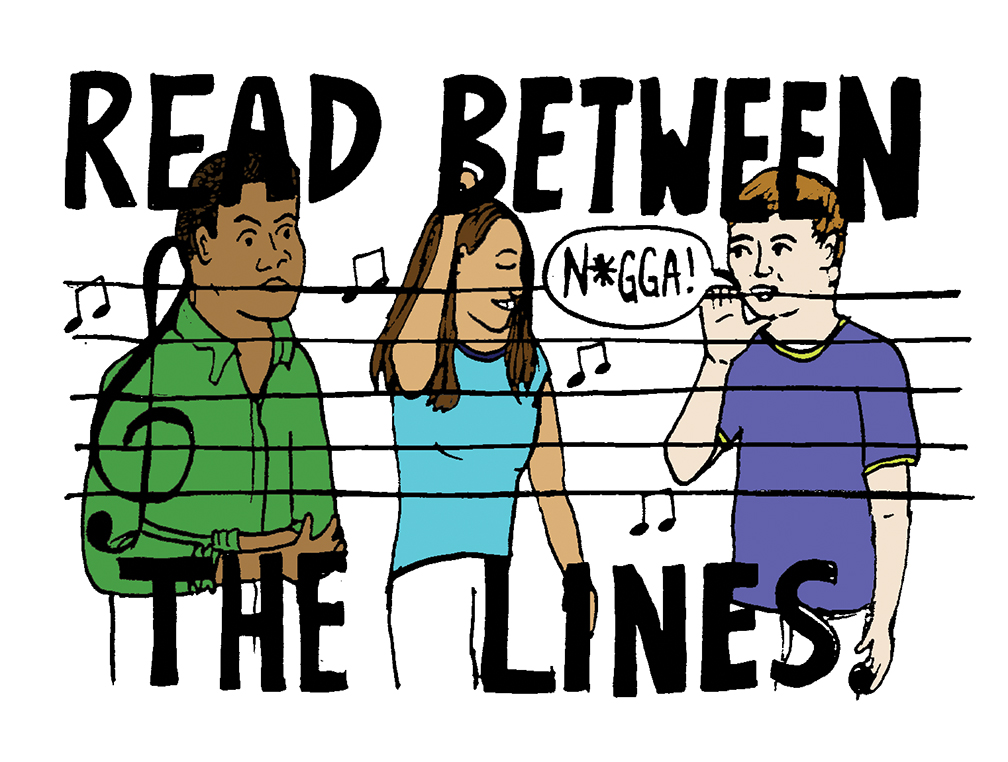

This exchange reminded me of similar situations that I’ve found myself in here at Bowdoin. On multiple occasions, I’ve had to choke back the impulse to make a scene in response to one of my white peers shouting the “nigga” word in my face. Even though the majority of these instances have come about as the result of somebody singing along to rap lyrics, the traumatic effect of a white person calling me “nigger” isn’t at all mitigated by the innocence of their intent. Moreover, the fact that some people only feel comfortable using racial slurs when they hear them in songs is a clear example of music influencing culture.

Often times, my adverse reaction to being called a racial slur will elicit a surprised and indignant response. “But you know that I’m not a racist, I was just singing along,” they’ll say. “You know that I was just joking around.” When rhetoric like this is used on me, all that I hear is, “For whatever reason, I consider myself beyond reproach when it comes to issues of racism and shame on you for suggesting otherwise.”

This is an easy trap to fall into at a place like Bowdoin. Liberal ideology dominates the political discourse on campus, and there seems to be a general sense that if you buy into that way of thinking, you are safe from being called out as a racist, sexist or homophobe. The truth is, though, that no matter how “woke” you think you are, it is still possible that your behavior might serve to reaffirm and reinforce certain oppressive power structures. Thinking back, most of the white people who have called me “nigga” have been very liberal, open-minded people. They’ve been people with whom I’ve shared Africana Studies classes, people who have led programs about issues that face people of color on campus, even people who have gone on to become class councilors and leaders in our student government. I feel as though it is not in spite of their political beliefs but because of them that they consider themselves too “woke” to be racist.

I’m guilty of this too. In my time here, I’ve read enough bell hooks and Judith Butler to feel comfortable calling myself a “woke” feminist. However, watching that boy scream in that girl’s face to silence her and call her a ho, I realized that I was complacent in what was going on. Not only was my house the space in which the exchange occurred, it was my playlist that contained the song that contained the problematic lyric. That troubling exchange only took place because I created the right environment for it—and I created that environment out of ignorance. Because of my opinions on music and culture, I hadn’t considered that the sexism in my music might influence the vibe of the party. Had I the gumption to doubt myself and recognize the role that I was playing in making my house a gendered, unwelcoming space, maybe that girl wouldn’t have left crying.

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy: