Why philosophy needs superstition

December 5, 2025

Celeste Mercier

Celeste MercierWe all know that Halloween is the scariest time of the year—at least according to the stories from folklore. Many practices around this holiday originate from traditional beliefs about the barrier between the living and the dead being at its weakest on Halloween. The jack-o’-lantern, for example, originated as a way to ward off evil spirits. As enjoyable as these traditions are for us today, they are rooted in something distinctly less fun: superstition. From the Latin “superstitio,” this signified an excessive dread or fear of the supernatural. A superstitious person was, in the Roman view, held to be a slave to tyrannical gods and barbaric rituals.

So it might seem surprising if I follow this by saying that Halloween is also the most philosophic time of the year. How can this be? Aren’t philosophy and superstition opposed to one another?

The answer is that philosophy and superstition have a mutual relationship—a strange case of interdependence, in fact. The superstitions or conventions that dominated the ancient Greek and Mediterranean world included the customary ways of life of various peoples, as well as the different regimes or law codes that governed them. Perhaps most importantly, these also included the many local divinities that were held to have founded or supported different cities.

The Greek historian Herodotus tells a famous story about the diversity of custom in the ancient world. The Persian king Darius calls together a delegation of Greeks and Indians from each end of his empire to ask about their funeral customs—for the Greeks, cremating their dead, and for the Indians, eating them. The king offers to pay each group however much money they want in return for adopting the other culture’s practice, but both flatly refuse. The story shows us that “custom is king among all peoples.” Herodotus uses this to argue that a previous Persian king was irrational because he had mocked Greek practices. But in doing so, Herodotus also alerts us to the arbitrariness of custom itself. After all, if custom really is king, then there’s no higher standard for comparing different customs, just like there’s no authority to appeal to above a king.

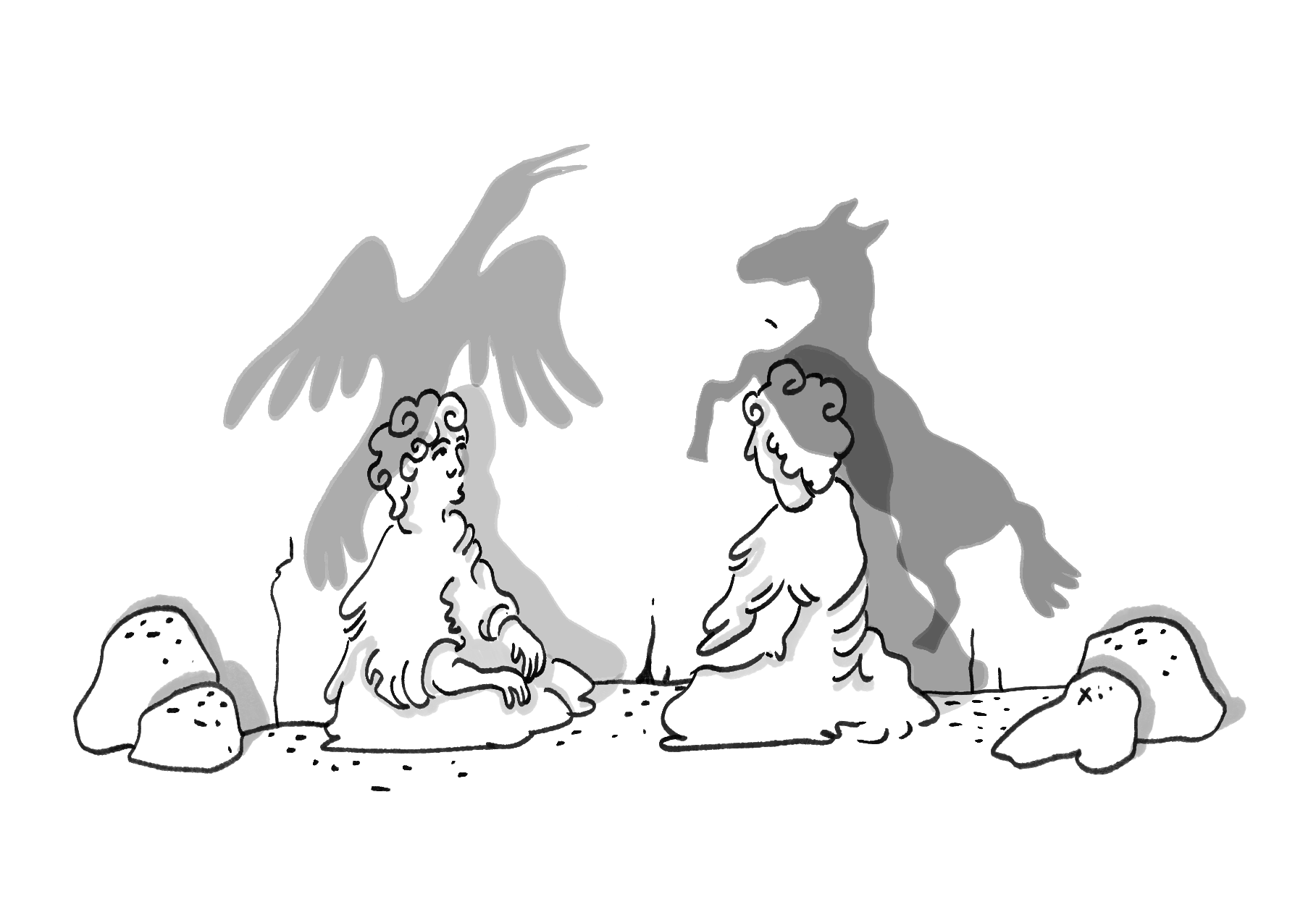

Greek political life threw this into even sharper relief. Each city had its own local gods held to have endorsed the city’s particular laws and customs (both of which are encompassed by the same Latin word: “nomos”). Yet the Greek cities were also in close contact with one another, a fact that inevitably gave rise to the uneasy feeling that no one city was as unique as it thought. If every city was claiming divine sanction for its way of life, then it appeared more likely that these conventions were simply arbitrary. It was the experience of these conventions—and the dissatisfaction that a few people felt with them—that gave rise to philosophy. This is exactly what Socrates depicts in his famous “Allegory of the Cave.” Like the prisoners in the cave, cities restrain their inhabitants through the force of superstition and custom. Philosophy allows us to transcend these forces, liberating us from convention by showing us a different—and better—standard for what is right and how to be happy. But the rejection of superstitious dread and fear can be dangerous, too: Socrates was prosecuted for not believing in the gods of Athens. And even in less extreme cases, it still might not be possible for us to live with no superstitions at all. Most people were perfectly content with the belief that their city and its laws were divinely sanctioned and angry to see these beliefs challenged.

Later thinkers tried to make use of superstition, hoping that it could be harnessed for philosophical purposes. Notable among these was Seneca the Younger. He was under no illusion of the sway that greed and vanity and cruelty held over humanity, especially their power to frustrate our search for a happy and fulfilling life. Against such forces, philosophy would have to deploy an equally powerful weapon. “Let them be held by a kind of superstitious reverence for virtue,” he writes of those seeking happiness. “Let them love her; let them desire to live with her and be unwilling to live without her.” If superstition was too deeply ingrained in us to be removed, then perhaps the lesson is to direct it toward virtue and philosophy rather than the conventional gods and beliefs. We could be drawn to do the right thing even if for the wrong reason (or, more accurately, no reason at all). Seneca acknowledges the power of custom and habit, but his recommendation also raises the question of whether unthinking philosophy is contradictory. If Socratic philosophy emerges out of dissatisfaction with convention, Seneca brings philosophy back towards the superstitions and habits that gave rise to it in the first place.

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy: