Portal to the past: A history of superstition at Bowdoin

December 5, 2025

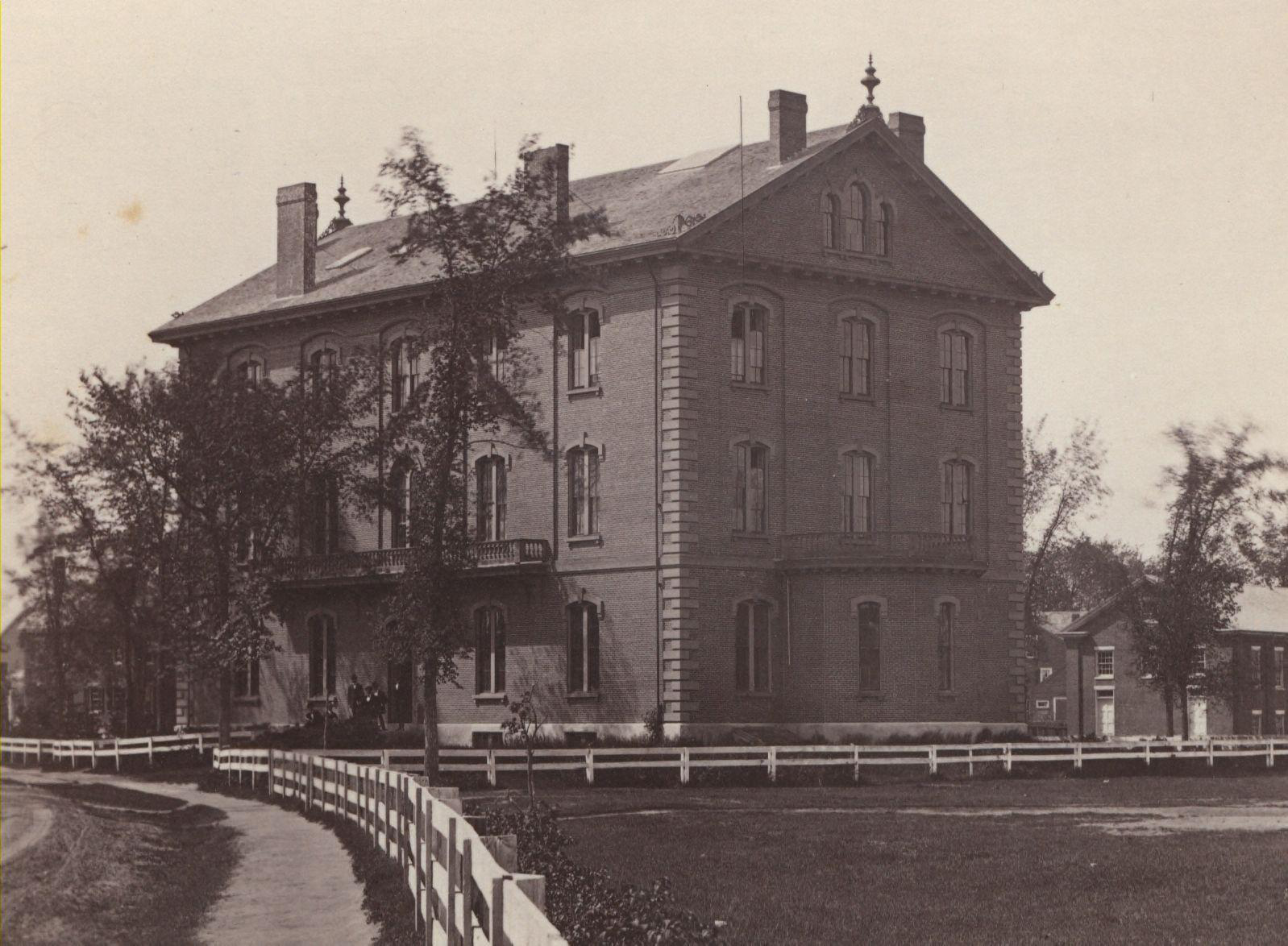

COURTESY OF SPECIAL COLLECTIONS AND ARCHIVES

COURTESY OF SPECIAL COLLECTIONS AND ARCHIVESOn Friday the 13th, 1953, Bowdoin sociology professor Dr. Isa Reiss gathered students and faculty in the Chapel to deliver a talk entitled “Superstitions.” According to the Orient coverage of the speech from November 18, 1953, Reiss explained common superstitions, such as the observance of Friday the 13th itself, hotels omitting a 13th floor and Bowdoin-specific superstitions like house teams not washing their jerseys after a victory during interfraternity football season.

Yet, Reiss’s most astute point was not about strange superstitions themselves but her remarks on their evolution.

“Dr. Reiss pointed out that it is usually the future generations that find the superstitions of the past generations,” the article reads. “Some of our most scientific procedures may be ridiculed by future generations when additional information is uncovered.”

The challenge in those lines is for the modern reader to dive into the past not only to memorize dates and recount key moments in history but to critically engage with past traditions and ideas.

Senior Interactive Developer in Information Technology David Francis is confronting this challenge. Francis chronicles history through superstition and has been collecting the College’s haunting myths since he started working here more than 25 years ago.

He hunts for stories by asking faculty, staff and students for their accounts of the paranormal. He has found the most success gathering tales from the custodial staff, people on campus who often work alone and at night.

A historian rather than a paranormal investigator, Francis does not try to verify the stories or find proof of the spirits people claim come out at night.

“I’ll admit I see this mostly as a study of folklore, and so I don’t see it like maybe a paranormal investigator would, looking for valid sightings. To me, that’s not that important,” Francis said. “I’m more interested in the collecting of the stories and gathering them…. It’s not a scientific endeavor.”

It may be difficult to see the historical value of a ghost story, but Francis uses these superstitions as an entertaining jumping-off point to explore the history behind them.

Francis also delves into the archives, where he seeks not a scientific explanation but a cultural one to understand how the story came to be, persisted and, perhaps most importantly, why people deemed it worth telling.

He gives the example of the Searles Science Building ghost, a haunting Francis has heard several people attest to with conflicting explanations. Some claim the ghost is of a girl from Brunswick who fell off the building during its construction, while others believe the ghost is of a custodian who had worked in the building for years and years.

When Francis looked into town records, he found no mention of a young girl dying during the construction of Searles. What he did find, however, was someone that did fall off a campus building and die: George Pottle, Class of 1932, who climbed onto the roof of the College’s observatory to look at the solar eclipse.

“Maybe [Pottle] is the person behind the echoing footsteps. So it’s kind of fun how it starts as just a ghost story,” Francis said. “It’s fun to build around it and see what it tells you about the time when those stories came up and what they actually meant to people.”

Another building that holds superstition is Adams Hall, which, according to Francis, is probably the building on campus most would call haunted.

Constructed in 1861, Adams Hall is the site of the former Medical College of Maine. The school was described as a distinct but closely affiliated part of Bowdoin, being overseen by the same president and governing board. There was animosity between the undergraduates and the medical students, largely due to intellectual elitism, as admission to the medical school was notoriously easy with a high dropout rate. In the end, the school closed in 1909 after a vote of the Governing Board—a bicameral model of governance they used until 1966, which is now replaced with the Board of Trustees—decided its closure was better than its continuing decline. Recent reports had criticized the school’s lack of clinical experience and inadequacies.

In Charles Calhoun’s 1994 book “A Small College in Maine,” which includes a brief history of the medical school, Calhoun suggests that the failure of the medical school is a ghost of its own.

“The idea of a medical school in the state has never completely vanished, a ghost of the ambitious effort … of the 1820s,” the book reads.

Corpses for dissection and anatomy labs were stored in the basement of Adams Hall. It is easy to give in to the eerie images of bodies and organs, especially when during a renovation of the building it was discovered some of the wood panels on the top floor were the lids of coffins used to transport the cadavers. Also, still left lingering on the top floor is the pulley hook used to string the coffins and bring the bodies up from the basement.

The coffin-lid floors and renovation of Adams Hall highlight an interesting relationship between superstitions, myths and history. Superstitions and myths grow from history, often lingering in the popular zeitgeist longer than established historical fact—so much longer, even, that people remember superstition in lieu of history, in which case the superstition becomes a portal to the past.

Francis’s time diving into Bowdoin’s superstitions and ghost stories has deepened his love for history. With future campus renovations, an old building’s haunting facade can be changed. For example, Sills Hall, with its previously faded wallpaper and decaying floors, is now one of the most modern buildings on campus.

What concerns Francis about these renovations, although he says they are often needed, is their forgotten history.

“The Dudley Coe building is scheduled to be demolished fairly soon. And I just point out, like, ‘Hey, there’s not a whole lot of buildings left that have dumbwaiters left in them, and that’s too bad,’” Francis said. “I’m sad to see them going. I feel like you need to remember these sorts of things that are slowly going away, a lot of the older architecture getting replaced.”

The history that superstitions and ghost stories provide are often more personal than the history learned in classrooms or from textbooks. The 1919 Bugle shares how students believed that a “Pink Gargle” lotion developed by a professor could cure all ailments and that shaving during the exam period garnered bad luck. These beliefs, that may seem groundless to us today, humanize the past and provide glimpses into the lives of previous members of the Bowdoin community.

“I’m interested in the more everyday life of people…. So I think that’s a lot of what I find interesting about these stories, how it reflects how people had to live,” Francis said.

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy: