The wilderness

December 6, 2024

Juan Chang

Juan Chang

From the inception of this column, my aim has been to prove American poetry’s importance. So what should I make of a critique that argues that America is not fecund ground for great poetry and preemptively identifies impediments that would prevent American poetry from reaching the heights of other traditions before it even had the chance to try? This, of course, is Alexis de Tocqueville’s 1835 critique of democratic poetry in “Democracy in America.”

Regardless of how wrong I think the aforementioned line is, I cannot deny that his critique holds some water. In his prediction for American poetry, he wrote that “in the end democracy diverts the imagination from all that is external to man, and fixes it on man alone. Democratic nations may amuse themselves for a while with considering the productions of nature; but they are only excited in reality by a survey of themselves.” Poetry using nature to characterize the experience of the individual is an American staple, and one of our major poets immediately comes to mind: Robert Frost. Nobody can deny Frost’s importance—the United States Senate itself has stated that “his poems have helped to guide American thought and humor and wisdom, setting forth to our minds a reliable representation of ourselves and of all men.” Most students could paraphrase the famous lines of “The Road Not Taken” and “Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening.” All this being said, I offer a poem that fits Tocqueville’s critique exactly.

In “Into My Own,” he writes:

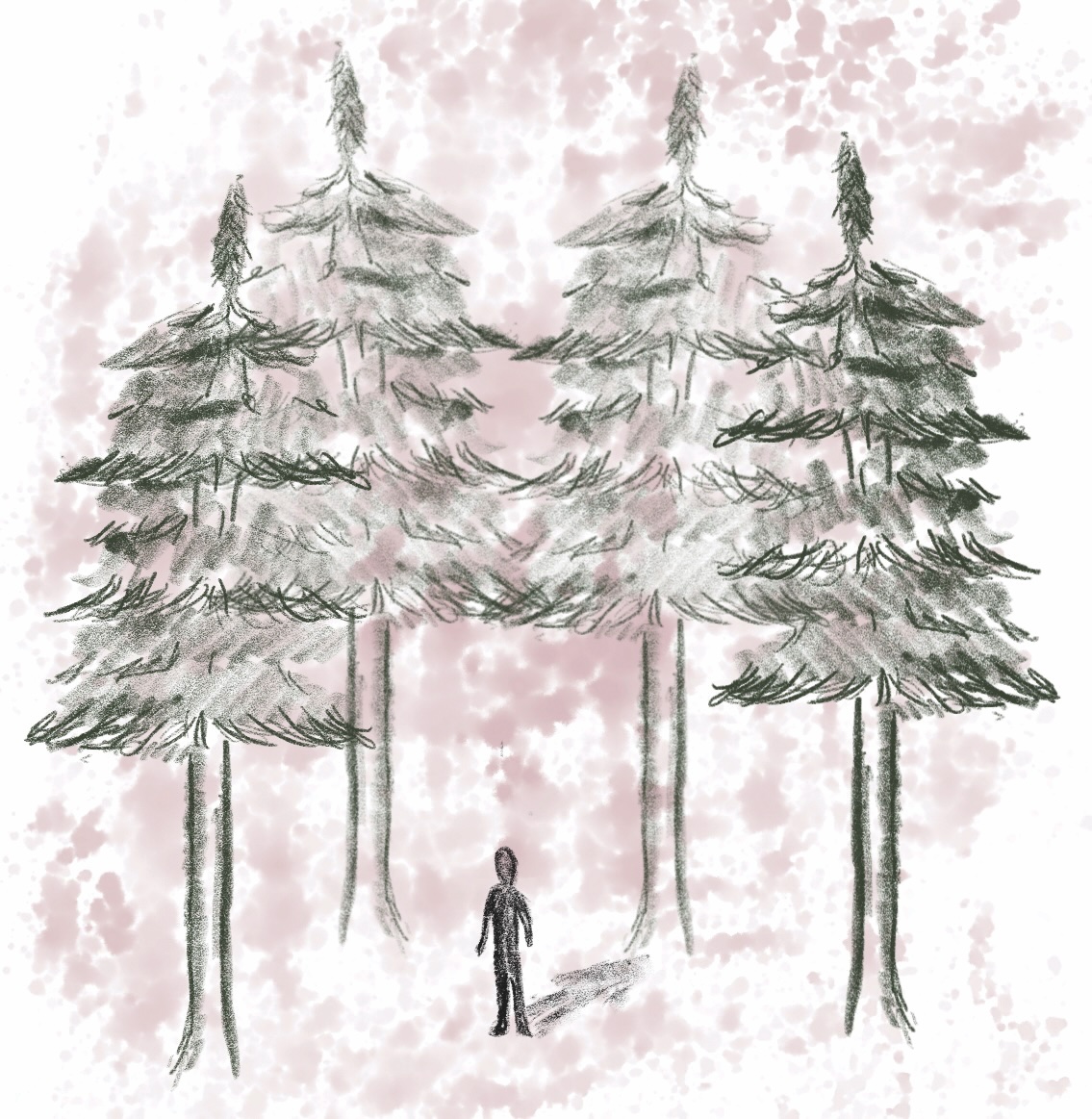

“One of my wishes is that those dark trees,

So old and firm they scarcely show the breeze,

Were not, as ’twere, the merest mask of gloom,

But stretched away unto the edge of doom.I should not be withheld but that some day

Into their vastness I should steal away,

Fearless of ever finding open land,

Or highway where the slow wheel pours the sand.I do not see why I should e’er turn back,

Or those should not set forth upon my track

To overtake me, who should miss me here

And long to know if still I held them dear.They would not find me changed from him if they knew—

Only more sure of all I thought was true.”

Here, Frost sees nature as the landscape of the mind. The more time he spends cloistered by rows of trees that protect him from being seen by others, the more he will be sure “of all I thought was true.” He does not want his loved ones to seek him out or find him changed, instead, hoping the woods will freeze him in time. The themes of “Into My Own” echo Emerson’s “Self-Reliance,” where he writes that “the voices which we hear in solitude … grow faint and inaudible as we enter the world” and are forced to conform. Emerson’s ideas are pumping blood at the center of “Into My Own.” We must understand and honor the mind, and its voice is strongest when we are alone. To honor it among the chatter of others is to relegate its power to that of a neap tide. Thus, Tocqueville’s premonition for American poetry comes to fruition.

As significant as Emersonian self-reliance is to American life and to “Into My Own,” Frost’s writing expands past it. Critic Robert Graves said that when we “feel the need of solitude,” we have the ability to “retreat to the companionship of moon, waters, hills and trees” within Frost’s poems. However, he writes, “Retreat should not be confused with escape.”

This distinction between retreat and escape is Frost’s most enduring message. Though poems like “Into My Own” are a fantasy of escape, both into the natural world and the deep wildernesses of the self, other poems involve a return from solitude. In “A Late Walk,” he describes a sojourn through withered fields. Watching leaves “rattling down” from barren trees, he assumes that they have been dislodged by the content of his thoughts. The last stanza is as follows: “I end not far from my going forth / By picking the faded blue / Of the last remaining aster flower / To carry again to you.” Using the fields to explore his mind, he returns a better whole, a flower for those he had retreated from to receive.

When you put “A Late Walk” in conversation with “Into My Own,” it becomes clear that the latter is satirizing escape. The speaker is not seeking out the wilderness to purify himself; instead, he wants a void where he can release his worldly frustrations and won’t force him to change.

I had meant to stray from his famous pieces, but I can’t ignore that “Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening” follows this same trajectory. Looking about him, in a desolate hollow, he considers the impulse to linger. However, he remembers himself: “But I have promises to keep / And miles to go before I sleep / And miles to go before I sleep.” Though we find peace in the solitude of nature, we have made promises that propel us back to society—not burdens that rip us from true self-expression, but bonds we want to honor out of love.

Though Tocqueville was correct about how we use nature to understand ourselves and expand our horizons, I do not think that demeans our poetic tradition. Instead, we become a part of the wilds around us. The barriers between ourselves and the natural world erode.

This is my final article in this series. If there is anything I can leave you with, it would be these words of Frost: “One thing I care about, and wish young people could care about, is taking poetry as the first form of understanding. If poetry isn’t understanding all, the whole world, then it isn’t worth anything.”

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy: